Carl Larsson's "Ett hem åt solsidan", or "Christmas Eve", 1955.

Christmas dinner … Making it more sustainable

Christmas dinner and other celebratory meals are a longstanding and valued holiday tradition for many families and friends. But how often do we think about where that food comes from? Or how long we and our descendants will continue to enjoy a sufficient, safe and nutritious supply of food?

Even though many of us enjoy an abundance of food, our food system has some substantial challenges in the short and long term. Some of the short term challenges include the local need for food banks, the worldwide problem of inadequate food supplies for approximately 1 billion people and the increasingly large environmental footprint for food production, overall. However, one of the largest long term challenges for our food production system will be to sustain the steady supply of nutrients in the form of food, from farms (where most food is produced) to cities (where most food is consumed).

Who will feed the soil?

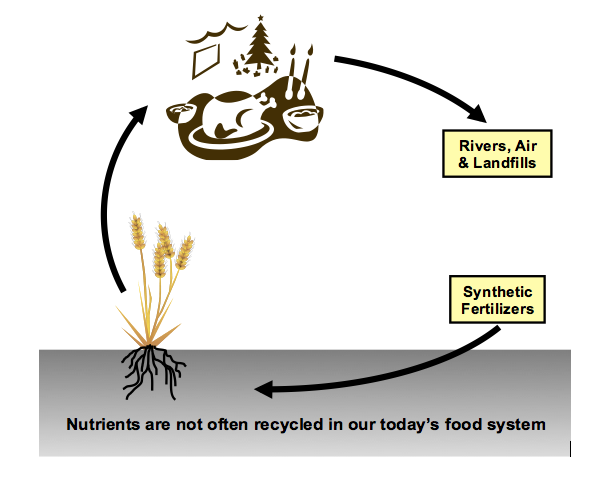

For the last 12,000 years, an increasingly smaller proportion of the world’s population is directly engaged in gathering or producing food, putting more and more pressure on each of the world’s farmers to feed more and more people. Mechanization, along with genetic and agronomic improvements to crop production have increased yields, but these increases have also resulted in larger exports of nutrients from the land, increasing our dependence on non-renewable and increasingly expensive sources of nutrients, such as synthetic fertilizers.

The overall net export of nutrients from farms is largely offset by processing huge quantities of non-renewable natural gas and phosphate rock into approximately 80 million tonnes of fertilizer nitrogen and 20 million tonnes of fertilizer phosphorus every year (for more information about the pros and cons of synthetic fertilizers for feeding billions of people every day, see books and articles by Dr. Vaclav Smil, an environment professor at the U of M who provides internationally respected analyses of these issues).

Why do farmers use so much synthetic fertilizer? Basically, the answer is because farms feed cities and cities generally don’t give those nutrients back to farms for recycling into our food production system. Why not? Generally because most current methods of wastewater processing that allow for nutrient recycling are more expensive than those that discharge those nutrients to nearby waterways (as in many small communities), release them into the atmosphere, or haul them into a landfill (as in many larger communities).

Kidney stones to the rescue

So, how do we move towards a food system that recycles nutrients more efficiently and effectively in our food production system? Part of the answer is in research. For example, several engineering, soil science, and plant science professors at the U of M are evaluating production and utilization of struvite, a novel fertilizer manufactured from wastewater for safe convenient recycling of phosphorus back into the food production system (although struvite is a novel fertilizer, it’s the same mineral that forms kidney stones).

Other professors are evaluating enhanced efficiency fertilizers that not only improve the efficiency of nutrient use by crops, but also reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other losses of nutrients to the environment. Complementing this work with commercial fertilizers, we have a team of professors collaborating at Canada’s longest running organic farming systems study, located at the U of M’s Glenlea Research Station; this study celebrated its 25th birthday in 2016. In addition, our animal scientists are developing livestock production systems that minimize overfeeding and wastage of nutrients and our plant scientists are developing cropping systems that will reduce our dependence on synthetic fertilizers by including more legumes as cash crops, green manure crops, intercrops and relay crops, for examples.

This type of work will not only reduce wastage of non-renewable sources of nutrients, it will also help us to minimize phosphorus losses to surface water and nitrogen losses to the atmosphere, where these nutrients intensify algae growth and climate change, respectively. However, researchers cannot address this challenge on their own. We also need farmers, consumers and society at large to work together and devote more effort and resources to the long term sustainability of our entire food system.

So, as we pause over the upcoming holidays to enjoy a celebratory meal with family or friends, let’s take a minute to think about where our food comes from. And let’s also remember how fortunate most of us are to enjoy a relatively bountiful and affordable supply of high quality food and also how important it is to invest a bit more than the bare minimum, in our farms and in our cities, to ensure a plentiful and sustainable supply of food for all families in the future.

Figure: The break in the nutrient “cycle” after food is consumed increases our dependence on synthetic fertilizers and threatens the long term sustainability of our food production system

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.