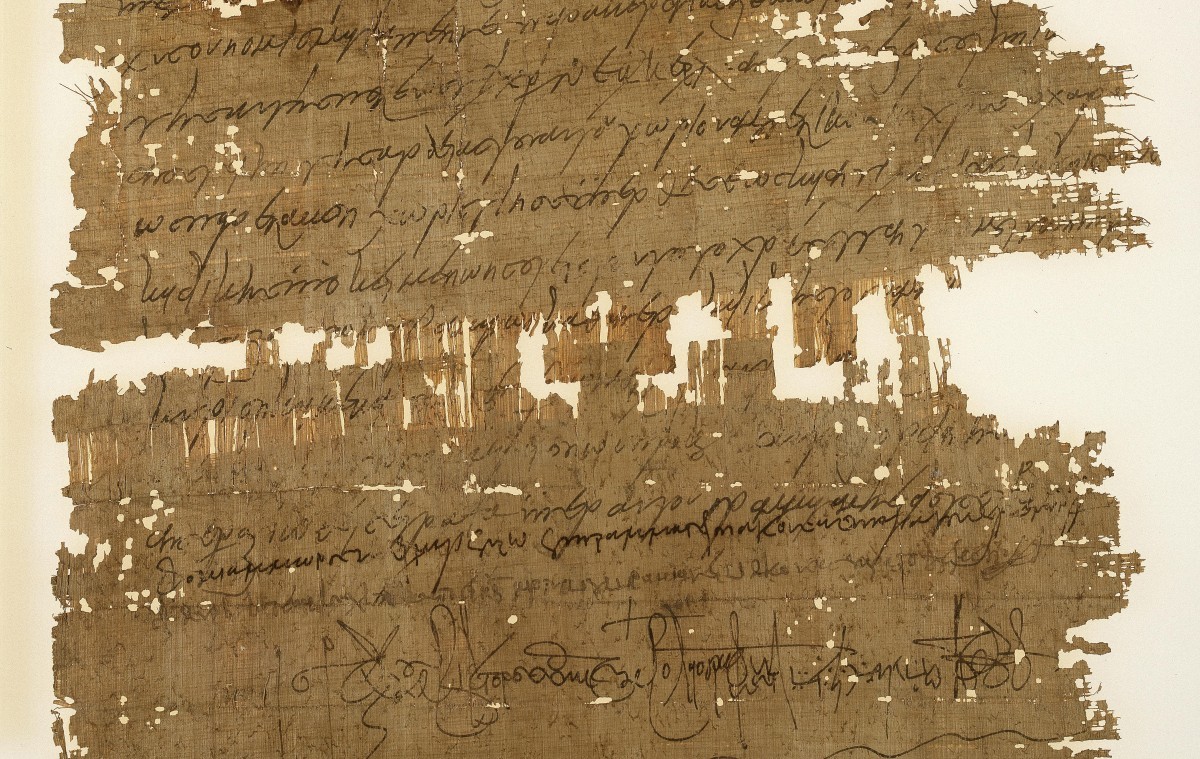

A papyrus from the sixth or seventh century CE detailing a loan of money // Photo: Papyrus Collection, Graduate Library, University of Michigan

When all hell breaks loose in Classics

Fifth Annual Lecture on Hellenic Civilization explores the mysteries of the latest poem from antiquity's greatest poet

A hundred years ago, just like today, new Sappho was big news.

“Out of the dust of Egypt comes the voice of Sappho, as clear and sweet as when she sang in Lesbos by the sea 600 years before the birth of Christ,” Joyce Kilmer wrote in the New York Times on June 14, 1914.

“This little song, whose liquid Greek syllables echo the music of undying passion,” was pulled from history’s locker by scholars who painstakingly excavated, deciphered, and pieced together 56 fragments of papyri – ancient paper made from a plant native to Egyptian marshes.

About one hundred years later, Dirk Obbink, a papyrologist at Oxford University, took a call from an anonymous private collector in London. The caller said he had a fragment of papyrus extracted from a mummy casing and perhaps Obbink could discern if it was something worthwhile.

“And this Oxford scholar went and read it and said, ‘Oh my god, this is Sappho.’ And when it was made public [in January 2014], all hell broke loose,” recalls Michael Sampson, a papyrologist in the U of M’s Department of Classics.

This fall will see the U of M host a trio of events centered on papyri—including the new poems by Sappho. The first is the Department of Classics’ Fifth Annual Lecture on Hellenic Civilization, which will be delivered by Leslie Kurke, the Gladys Rehard Wood Chair and Professor of Classics at the University of California, Berkeley. Her public lecture is titled “Sappho on Papyrus: Reading Some New Poems” and will take place on Sunday, Sept. 25, at 3 p.m. in 118 St. John’s College. It is free and open to the public.

Then, in October, Sampson and undergraduate student Amber Leenders are co-curating an exhibit in the U of M’s Archives and Special Collections based on his SSHRC-supported papyrological research. The exhibit aims to provide a general introduction to papyrology, but especially to the 1920 purchase of some 534 texts for the University of Michigan.

What: Ink and Sand: an Exhibit on Greek Papyri Purchased by Francis Kelsey and Bernard Grenfell for the University of Michigan in March-April 1920

When: Oct. 12, 2016, to Jan. 13, 2017

Where: Archives and Special Collections, 3rd Floor Elizabeth Dafoe Library, M-F 8:30-4:30

Admission: Free and open to the public

To formally open the exhibit, Associate Professor Todd Hickey from the University of California, Berkeley, will deliver the lecture “Kelsey, Grenfell and the Dealers”on Oct. 19 at 2:30 p.m. in the U of M’s Archives & Special Collections (3rd Floor Elizabeth Dafoe Library). Based on new archival research, this public lecture will describe the scholarly shopping spree in which the papyri Sampson’s research focuses on were acquired, and it will shed light on the Egyptian antiquities market of the era.

“When this latest [Sappho] work surfaced, the papyrological community was very… curious. That is the word I’ll use. But anyone who works in ancient Greek literature – classicists broadly – was very excited: it’s new Sappho! We know so little about her work that any new material is cause for excitement,” Sampson says.

“It’s a strange poem,” he says, “because it mentions two of her brothers, who we know from other sources were part of her biographical tradition. Herodotus, for example, recounts that Sappho criticized one of them for freeing an Egyptian courtesan. And if that’s in fact what’s happening in this poem, then we have very peculiar insight into the family dynamic of Sappho’s home. But there’s still work to be done. I am certain that Professor Kurke will have very interesting things to say about the poem; we’re very excited in Classics to be hosting her.”

Michael Sampson examines a papyrus in the University of Michigan’s collection. // Photo: Monica Tsuneishi

Q&A with professor Michael Sampson

UM Today: Was Sappho respected in her time by her contemporaries?

Michael Sampson: That’s a complicated question. So the question is which Sappho are we talking about? I’m not suggesting there were multiple women named Sappho who were poets in antiquity. But everyone has their own construct of Sappho. I would say that in antiquity she was greatly respected as a lyric poet. Plato, the philosopher, called her the tenth muse in an epigram. Everyone acknowledges that she is fantastically good as a songwriter.

Greek comedy, however, makes a caricature of her and puts her on stage as a comic figure, subject to ridicule and abuse. And a lot of this has to do with the fact that she comes from the island of Lesbos. There was a tradition already in antiquity that she engaged in same-sex relations with other women on Lesbos: we get our word Lesbian from this. And so on the comic stage she becomes a bit of a dirty old woman with insatiable sexual desires.

What’s the big deal about her poems? Why do people get so excited and why do they matter? How do you explain the importance of these works to someone who thinks they’re not worth much attention in the modern world?

It’s easy to sell new Sappho to the general public because she is famous. She was famous in antiquity. And we have, really, only scraps of her output: until papyrology as a discipline came along (in the last 130 years or so), we had one complete poem by Sappho, and that was it. The rest were snippets or quotations or fragments. But once papyri began being excavated and appearing on the Egyptian antiquities market, all of a sudden we had new poems of Sappho coming out. The New York Times ran a story when one of the new fragments was published in 1914 because it was that important.

So for the members of the public who ask, ‘is this really a big deal?’ Yeah, it really is a big deal.

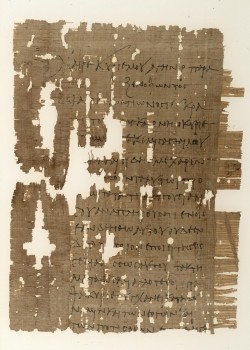

A letter from the late third or early fourth century CE // Photo: Papyrus Collection, Graduate Library, University of Michigan

My research is where it gets a bit harder. Sappho is prominent. She’s famous. But most papyri are not new works of ancient literature. Most papyri in collections around the world are documentary – tax receipts and accounts. Historians go crazy for this stuff because it’s eyewitness testimony to the way the Roman province of Egypt was administered. And those documents outnumber literary texts by a ratio of about 8:1; it’s hugely disproportional.

No matter how you think about it, it’s miraculous. We have eyewitness, hand-written testimony about the daily life of communities in antiquity. It’s just that poetry and literature dominates the popular imagination: if you think about ancient literature, most of it survives because it was copied and recopied and recopied. But it’s the broken telephone game; if you copy things, over the course of hundreds of years mistakes creep in. What papyri allow us to do is to leap over that entire tradition and go back to the source. If you want to know how a community worked in Roman Egypt, these are the documents that actually tell you, and a lot of the material we present in the exhibit is documentary.

What is your research in this area?

The work I’m doing is focused specifically on 534 papyri that were purchased in 1920 by professor Francis Kelsey at the University of Michigan. He went to Cairo on a shopping spree, buying material that could be used for research and teaching at his university. These were the founding documents of Michigan’s collection, which has since grown to be the biggest in North America.

Yet, almost 100 years later, more than half of them haven’t been read or published. So my job as a papyrologist is to go and read someone’s scribbling, from almost 2,000 years ago (and in ancient Greek!) and to publish it so that historians or others who are investigating the history of Egypt of the time can use the material. Not everyone can read a papyrus (or ancient Greek!) The exhibit is an opportunity for me to share that work with the broader public, and for my co-curator Amber to enjoy a unique learning opportunity.

…Every papyrus sheds new light on history. And every papyrus, for me, is a surprise. I never know what I’m going to get when I sit down and try to read one.

Reading it is part of the challenge because the writing is usually scribbled. Plus, it’s in ancient Greek. So you have to decipher the letters, make Greek out of it, and then put the Greek into an English that can be understood. That’s a challenge!

Sampson’s research is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.