Panels on the relevance of Treaties and Traditional Knowledge Keepers

For the first session of Indigenous Awareness Week, which takes place March 16 to 21, panelists will come together to discuss the relevance of Treaties for contemporary Canada and its future. The closing day of panels, Mar. 20, will include opening ceremonies at Migizii Agamik and will feature a full day of dialogue with Elders and Knowledge Holders about relationship-building.

As Deborah Young, executive lead, Indigenous achievement, at the U of M notes that the week is in part about “building a consciousness in the university. And this is also what Treaties are all about — building a relationship.”

The key session, “What Are Treaties and Why Are Treaties Still Relevant?” takes place in Senate chambers on Monday, March 16, from 1:30 to 3:30 p.m.

Two panelists in the Treaties session are Manitoba Treaty Commissioner James Wilson and Jean Friesen, a historian in the U of M’s history department in the Faculty of Arts who is also a member of the Treaty Commission of Manitoba’s Speakers Bureau.

UM Today spoke with both Friesen and Commissioner Wilson about Treaty 1 and the ongoing relevance of Treaties. Two illuminating interviews: we open with Friesen’s historical perspective and and wrap up with Commissioner Wilson’s succinct summary.

***

Jean Friesen, historian

UMT: What is your work and research about?

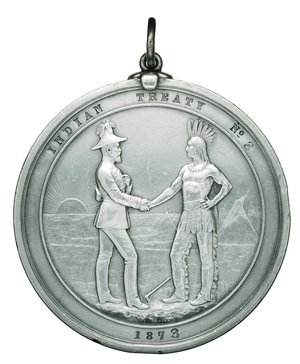

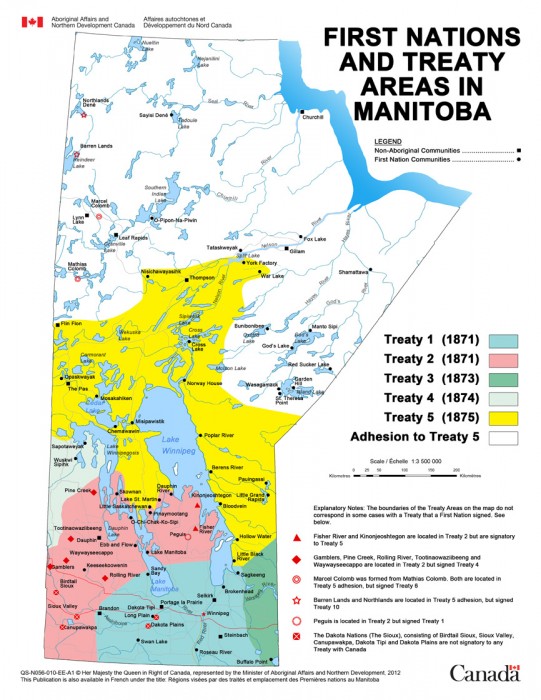

Jean Friesen: My work has been on Treaty 1 in particular — it’s the first treaty that Canada made after Confederation, which why it’s called number 1. It doesn’t mean it’s the first treaty in Canada; it’s the first one that Canada made after 1867. It’s also includes the lands on which the University of Manitoba is located, and a portion of Southern Manitoba.

UMT: What is your role with the the Treaty Commission of Manitoba’s Speakers Bureau?

Friesen: I’ve worked with Commissioner Wilson as well as Elder Harry Bone [who is also on the panel] as part of the Treaty Commission’s Speakers Bureau. We’ve given talks to teachers and people who are developing curriculum, and church groups and public interest groups.

The Speakers Bureau is a mixed group — there are Elders, lawyers, some historians — and usually the Treaty Commission staff puts together a small group, depending on what the client group wants — and we might spend a couple of hours or workshop over a couple of days. It will normally include an Elder to open the sessions and to set us all on the right path.

Each of the prairie provinces has a treaty commission.Saskatchewan’s has been in existence the longest and both Manitoba and Saskatchewan treaty commissions have excellent websites that can be a great help in finding additional resources. Teachers, in particular, have found them very useful.

UMT: Why are Treaties are relevant today, and why you think it’s important that this topic is included in the panels?

Friesen: When I talk to public groups about Treaties, I usually start with the Treaty Commission’s phrase, “We are all Treaty people.” It’s intended to raise the question of Treaties in people’s minds … that sense that there were two peoples that negotiated the Treaties, who agreed upon them, who made a covenant.

For those people who are not Indigenous … I think there should be an understanding of the context of the negotiations and the agreements that were made.

Friesen: When I talk to public groups about Treaties, I usually start with the Treaty Commission’s phrase, “We are all Treaty people.”

Because — and here’s the reason why — for the presence of non-Indigenous people in Manitoba or the Prairies where the major Treaties exist — is that this is the basis of our wealth. Many people have come here and made comfortable livings, whether they own property or a business, or whether they are a major corporation — and that wealth has come from the land and the resources.

This formed part of the subject of the negotiation: The permission for peaceful settlement and the use of some of these resources comes from those treaties. So in that sense, it’s an obligation we all have. To understand them and to understand that we’re all Treaty people in that sense. I often say that I wish I’d had that phrase when I began teaching, because it’s a very good encapsulation of the issues and of helping people to think about it.

UMT: Is there anything else we should know about Treaties?

UMT: Is there anything else we should know about Treaties?

One of the ways that I talk about it — and I do this in my university classes as well — is to try and get across to non-Indigenous people that Indigenous people always made Treaties. They made Treaties with each other long before Europeans came here. They made Treaties for various reasons — for resource sharing, for rights of passage across their lands — and this Indigenous political thought carries over into the Treaties of the late 19th century. So again, it’s trying to get across that sense of two people negotiating over the future.

I guess the second point I always try to make is [that] a lot of people in … 20th century Canada have thought about Treaties as something in the past. A long time ago. And indeed Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chrétien tried to get rid of the Treaties in 1969. I don’t know how much you know about the White Paper, but that was an attempt to get rid of Treaties. A single stroke, by a non-Indigenous government, to get rid of negotiations and Treaty agreements that were arrived at by two parties.

And so I think, even though this failed, it contributed to a general sense that these [Treaties] were in the past, something to be left behind.

I go back to the language of the Treaties and speeches that were made [at Lower Fort Garry] at the time of the Treaties. Both sides — but particularly on the Indigenous side, if you look at the speeches, the Indigenous leaders in Southern Manitoba [for] Treaty 1 — made the point over and over again that they were thinking about the future.

And some of the speeches that they make are very evocative… Here’s something from one of the speeches [by an Indigenous leader]: “We must find ways to feed our children.”

“We must find ways to feed our children.”

And the second speech that always resonates with me is “Grant us wherewith to make our living.” We’re going to have to live in this land with you; make sure that by this Treaty, we have enough to make a living and that we are able to feed our children.

That sense of an economic future is what comes through at the time of the making of the Treaty.

So that sense that they are about the past and it’s all over — no. It’s about ensuring that we are true to the spirit of those Treaties, and I sometimes define that as a continuing obligation, to each other.

***

Commissioner James Wilson

UMT: Can you tell us about your role as Commissioner in relation to Treaties?

Commissioner James Wilson: My role is to restrengthen, rebuild and enhance the Treaty relationship. To get away from the [1876] Indian Act relationship, and we do that through education, research and facilitation. We’ve got a major education program, where we are bringing Treaty education into the schools in Manitoba, Kindergarten to Grade 12. We are in 400 schools so far; we’ve trained just over 1,000 teachers — who’ve done two days of training, where they hear from Elders, historians, legal experts. And then they get a kit, with about $500 of resources, for their school.

Commissioner Wilson: “My role is to restrengthen, rebuild and enhance the Treaty relationship, to get away from the Indian Act relationship.”

In research, we have two big projects on the go — an atlas and an oral history project. That’s been about eight years of research going into those. With facilitation, our job is to facilitate a dialogue between first nations and the federal government, provincial government and business. And there has been the most interest in the area between First Nations and business. Because there’s not a lot of opportunities for First Nations to engage with the business community-at-large. We are helping to foster that.

UMT: So it’s both education within the public school system and the wider community as well.

Commissioner James Wilson: Yes, for sure. An example of why [education about Treaties] is relevant would be … an issue like Kapyong [Barracks, the former military base on Kenaston Boulevard still tangled in a court battle; six First Nations groups are hoping to turn the site into an urban reserve based on a Treaty land entitlement process].

Kapyong exemplifies the misunderstanding and lack of context in the relationship right now. So we can come in and say, so what is the context? … Why do First Nations in Manitoba have land titles that is owed to them? What are urban reserves that have happened elsewhere, what are the success stories? And then we can bring together the business communities with First Nations leaders, and say, okay, how can we work together?

So, there are a lot of contemporary issues that work with that.

UMT: Can you explain more about the importance of, as you say, getting away from the Indian Act relationship and enhancing the Treaty relationship?

Commissioner Wilson: Initially the relationship between First Nations and Canada, or non-First Nations, was codified through Treaty. In essence, the best way I’ve heard the Treaties described is by Jean Friesen, as “enduring relationships that lead to mutual obligations.”

Both sides are saying, okay, if we want to work together, and we want to create opportunities, here’s what we have to do. And First Nations had a long history of signing Treaties and negotiating Treaties. And so they said, here’s what we do, tere’s certain opportunities we want — we want education, we want training in certain things, like agriculture and farming. We want to be able to hunt and fish and trap — so the Treaties are about creating opportunities to adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

And not to say that they were perfect, but they were pretty solid agreements — two people with very different world views coming together.

But since then, the Indian Act was introduced [in 1876] and the dysfunction in the relationship stems from the Indian Act, which created a hierarchy, created dependency within First Nations. It outlawed a vast amount of things, from travel to working off reserves to selling goods off reserves, tools, ceremonies, it brought in residential schools — it really disempowered First Nations.

UMT: That’s a very succinct way of showing the need for bringing back the Treaty relationship.

Commissioner Wilson: Yes, and that’s something that both the federal government and First Nations agree with. They both think that’s how we can move ahead.

UMT: So the Treaties were already in place, already a negotiation, rather than a law-based, restrictions-based regime like the Indian Act. The Treaties are kind of like an ongoing, living agreement.

Commissioner Wilson: Yes, it’s kind of like a marriage, right? People use the analogy of a marriage. The ceremony itself is just the beginning, the beginning of the work.

But you are saying, ‘we’re going to work together.’

— Mariianne Mays Wiebe

>> See story on Indigenous Awareness Week here and more on individual panels here.

The closing day will include opening ceremonies at Migizii Agamik and will feature a full day of dialogue with Elders and Knowledge Holders about relationship-building. See our story about Indigenous Awareness Week, including the full schedule of events here.

The key session, “What Are Treaties and Why Are Treaties Still Relevant?” opens the week and takes place in Senate chambers.

A video of proceedings will be posted on the Indigenous Connect website.

***

What Are Treaties and Why Are Treaties Still Relevant?

Location: Senate Chambers, 262 Engineering Information and Technology Complex

Date and time: Monday, Mar. 16, 1:30 p.m. to 3:30 p.m.

By definition, Treaties are negotiated agreements that clearly spell out the rights, responsibilities and relationships of First Nations and non-First Nations. But in practice, they are far more complex and often lead to animosity and exhaustive court cases. We Are All Treaty People and it is essential that we understand their origins, as well as how they will play a role in shaping the future of Canada.

Panelists

Elder Harry Bone

Jean Friesen, associate professor, history, Faculty of Arts

Ovide Mercredi, Special Advisor to U of M

James Wilson, Treaty Commissioner of Manitoba

Relationship Building

Land, Resources, and People: Elders’ and Knowledge Holders’ Perspectives

Location: Migizii Agamik and Marshall McLuhan Hall, University Centre

Date and time: Friday, Mar. 20, 8:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.

Join us at 8:00 a.m. to open the day with traditional pipe, water, and fire ceremonies* at Migizii Agamik – Bald Eagle Lodge. This will be followed by two sessions in Marshall McLuhan (10 a.m. – Noon and 1:00 p.m. – 3 p.m.) when Elders and Knowledge Holders from across the country will share their perspectives on treaties, land, and resources.

*PROTOCOLS: All traditional protocol will be followed. For female guests please wear a long skirt. If anyone is unsure about traditional protocols, please contact the Aboriginal Student Centre at 204-474-8850. Please note that all cell phones must be turned off. Recording of the ceremonies in any way is not permitted (no photos, videos, audio recording or social media posts).

Thank you for respecting these protocols.

Traditional teachings and reflections by:

Elder Harry Bone

Margaret Lavallee, Elder-in-residence at U of M

Mel Chartrand, co-founder/co-director/lead behavioural health specialist, Eyaa-Keen Healing Centre

Shirley Chartrand, co-founder/co-director/lead behavioural health specialist, Eyaa-Keen Healing Centre

Elder Levinia Brown

Norman Meade, Elder-in-residence at U of M

Elder Garry Robson

Elder Florence Paynter

Ken Young, lawyer

Elder Charlie Nelson

Elder Dave Courchene Jr.