Grounded perspective

Artworks connect to the natural world

Sarah Ciurysek did not spend her childhood dreaming of becoming an artist. But as an artist she has come to realize, and appreciate, just how much that childhood, largely spent roaming the great outdoors at her family’s northern Alberta farm, has impacted her artwork.

Sarah Ciurysek, Associate Professor, School of Art

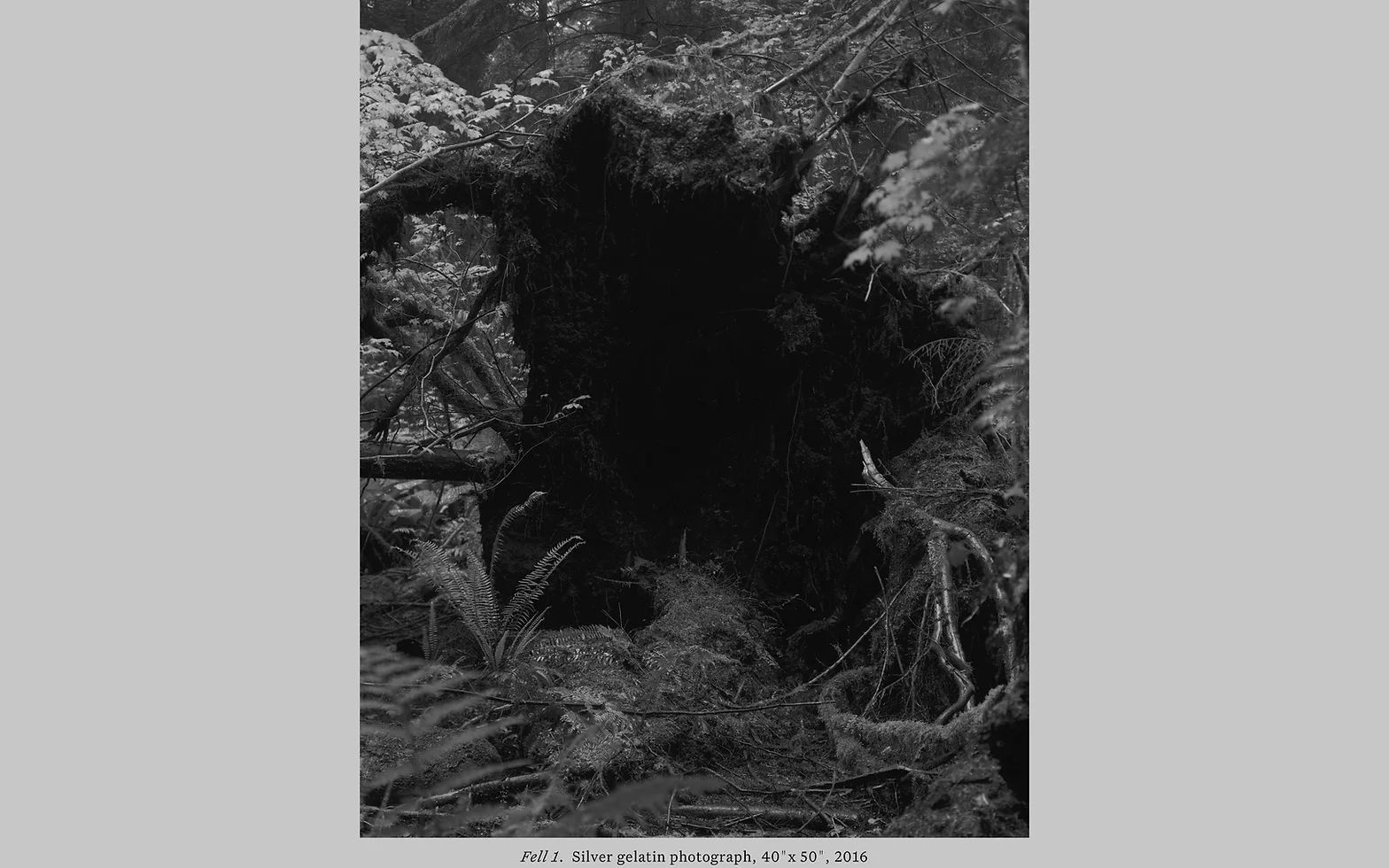

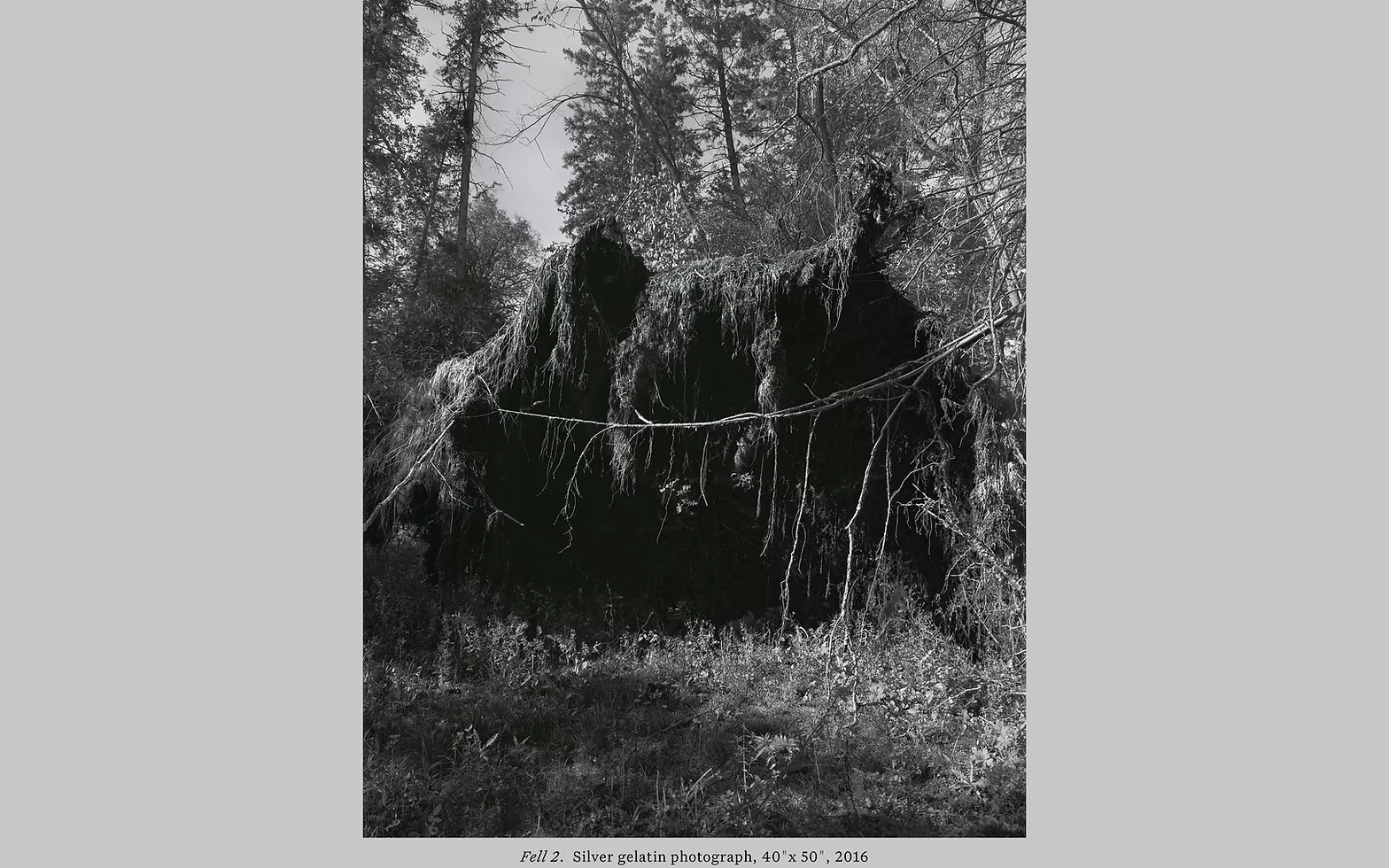

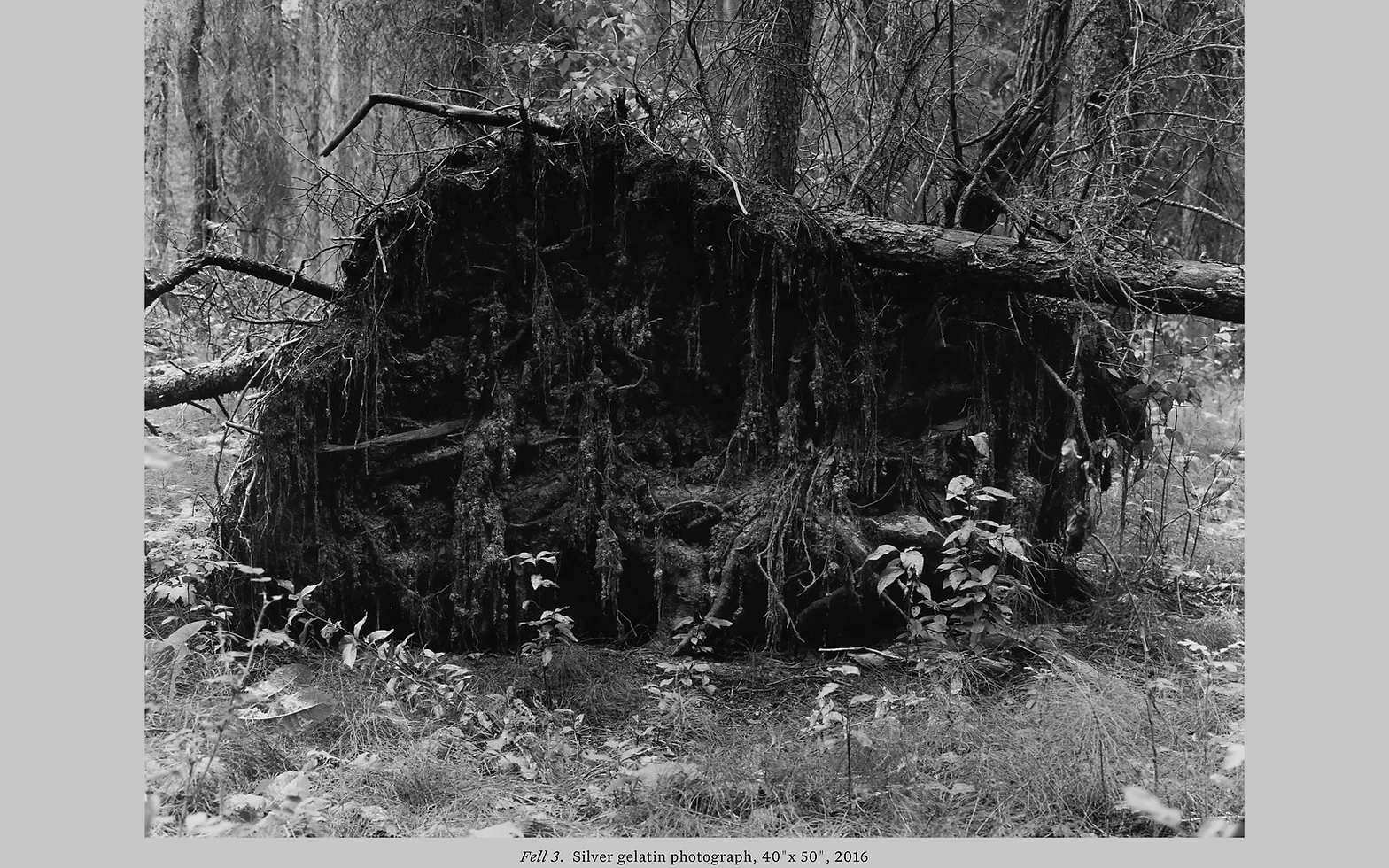

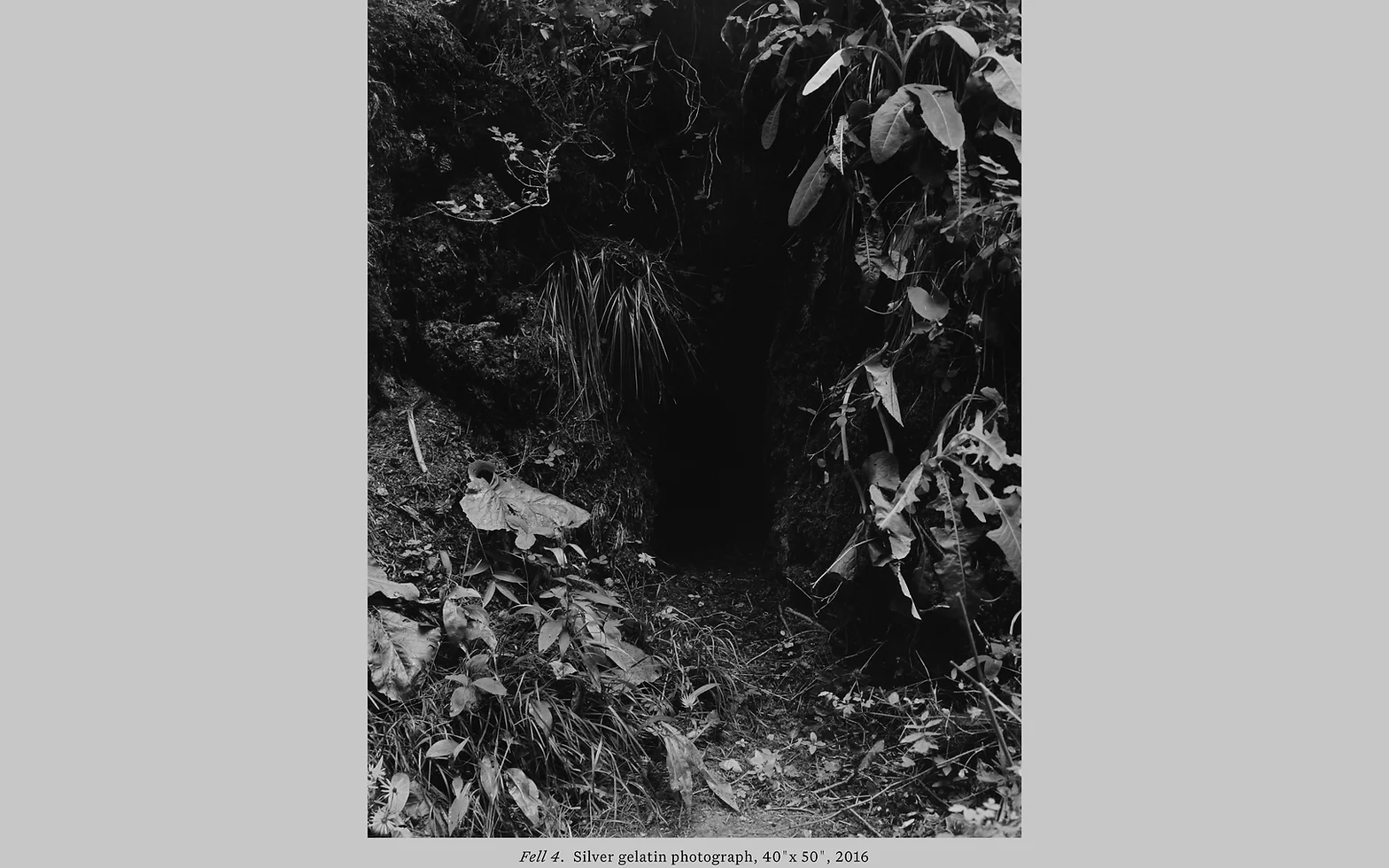

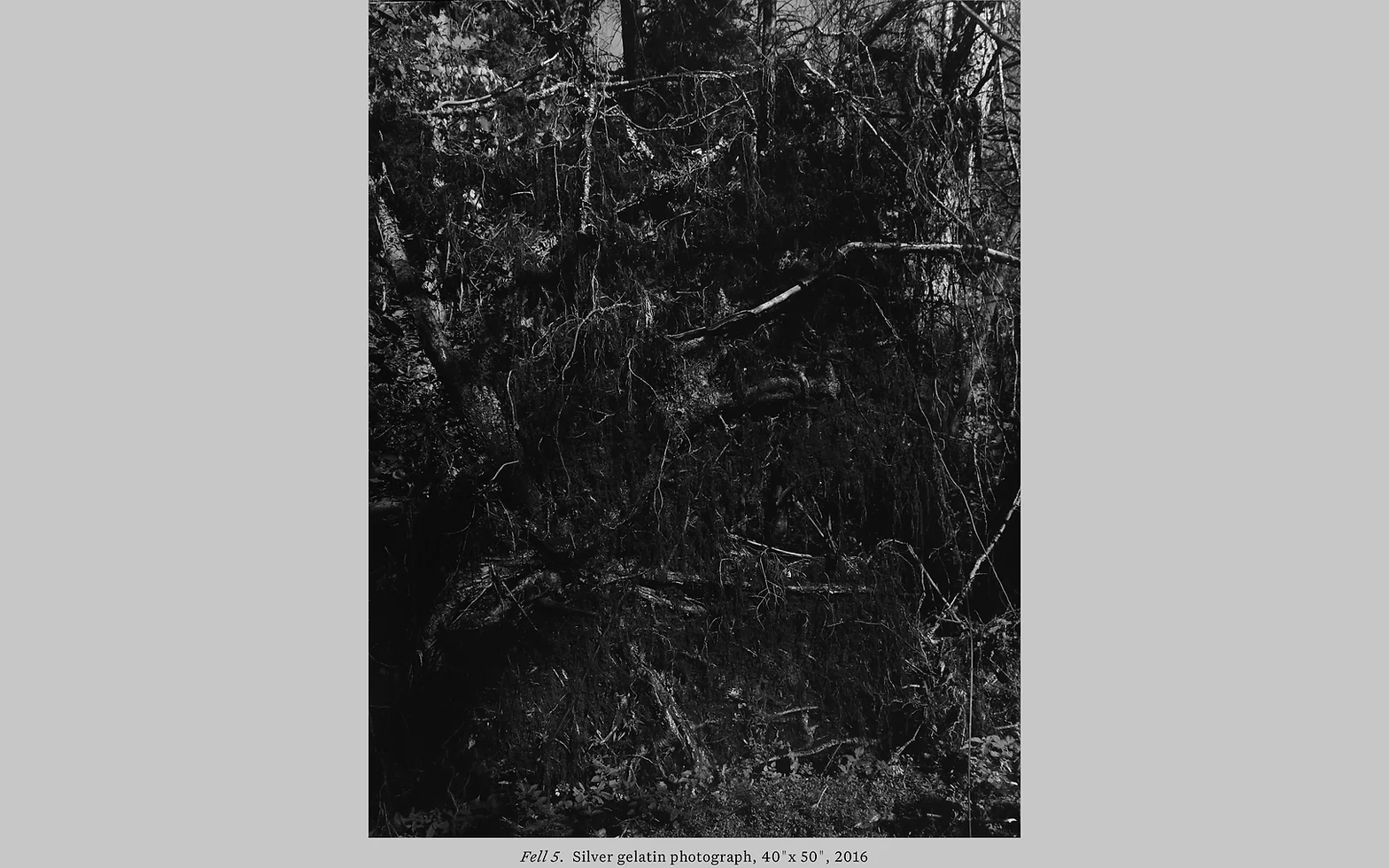

Ciurysek is a land-based photographer and multi-media artist who is constantly exploring the existential and emotional relationship between humankind and the land. Many of her images reflect barren branches, uprooted trees, graves, voids and other replications of death and decay, but much of her work also draws attention to the life-affirming properties of the land.

“A lot of my works are most obviously about death,” Ciurysek explains, “and that is a subject matter that comes to the fore quite quickly. But at the same time, I’m usually aiming to encourage for the viewer a sense of returning to their body and, in spending time with the artworks, to just feel grounded themselves and present and alive.”

Her works, she adds, may be physically dark, but not necessarily heavy or sad. “They feel inextricably tied in with the experience of living, of being human.”

Ciurysek was drawn to art, and photography in particular, through political activism, and has remained committed to photography because of what she perceives as the medium’s democratic nature.

While studying political science with a focus on Indigenous self- determination at the University of Alberta, Ciurysek worked for the student newspaper as a photographer. That combination of work and study led, after graduation, to a job with the Metis Settlements General Council in Alberta, where she edited a community magazine.

“From this, I realized my deeper interest in visual art and my hopes for how art can contribute to social change,” Ciurysek says.

Ciurysek enrolled in the photography program at the Emily Carr University of Art and Design—receiving rigorous technical and conceptual training—and then went on to Concordia for a MFA. She joined the University of Manitoba as an associate professor at the School of Art in 2013.

“When I was in grad school in Montreal,” Ciurysek says, “I began to see that my experience with land was rather unusual. I felt a familiarity and comfort with the ground that I started to understand not everyone had, and I wanted to share that proximity to the ground that I felt with others.”

Collage-in-progress, 2022.

That desire, she adds, coincided with a determination to celebrate rural perspectives, which she found to be missing from contemporary art at that time.

“Channeling the pleasures and powers of the ground through my photographic installations seemed right to me,” the artist asserts.

Those pleasures and power are evident in both Ciurysek’s early and current work, including the 2016 photographic series, Fell, which depicts the dark root balls at the base of trees that have fallen over, and the photographic mural of intertwining tree branches that she is currently working on during a six-month research leave.

Ciurysek works primarily with physical photographs that have a material existence, and her images are often site specific, representing the ground as it really appears. Her 2011 photographic mural, Landscape, is an anomaly, made up, as it is, of soil images reconfigured and recomposited from old excavation negatives. Ciurysek’s sonic photographic piece, Dear Mary, is an even greater departure from her usual practice. Dear Mary, part of a commissioned exhibit at Loughborough University in England, pays tribute to an older woman’s life as a farmer, while evincing Ciurysek’s feminist perspective and determination to represent unknown or undervalued women’s experiences.

Landscape. Toner photographs printed on Tyvek, total size 9’x8’ (separated in 3 panels), 2011 Photo: Blaine Campbell

Many of Ciurysek’s installations—which have been exhibited across Canada and in the UK, Austria and South Africa— are intentionally designed to require an unusual viewing experience, such as leaning over the artwork.

“I am also hopeful that my artworks encourage the viewer to consider their relationship to the ground and their relationship to the natural world.”

“I believe that triggering the viewer’s senses and body heightens the emotional impact of the stories that are embedded in the works,” she explains. “I am also hopeful that my artworks encourage the viewer to consider their relationship to the ground and their relationship to the natural world.”

Ciurysek encourages that same consideration in her students, whether she is introducing them to non-traditional research methods at an outdoor class at FortWhyte Alive or teaching them darkroom secrets in the School of Art’s analogue photography facilities. Those facilities, she says, are “amazing,” and are just one representation of the many ways in which the U of M so generously supports her research, her art making, and her determination to connect others with the land.

Towards Decolonization

Sarah Ciurysek’s research and resulting artwork have consistently reflected her ties to and passion for the land. But her approach to that research and artwork, she admits, has been as a “settler artist,” an artist who benefits from accepted art practices, even though they may be rooted in colonial power imbalances.

Ciurysek is now intent on changing that trajectory and focusing more of her practice on decolonization.

“I have been very committed to intercultural work and decolonization in my work as a teacher, and as a person, ” she says, “but I haven’t explicitly worked on decolonization in my own creative research yet.”

Ciurysek’s commitment to exploring decolonization will involve creating future photographic based artwork that clearly engages with the topic. But the commitment will also involve a lot of looking back.

“Some of my work ahead is to go back and reexamine my past artworks to see if those artworks have been complicit in conventional colonial landscape art practices,” she explains.

The first step in reexamining that past will mean thoroughly researching the history of colonization in northern Alberta’s Peace River region in Treaty 8 territory. That is where Ciurysek grew up and where she first connected to, and was inspired by, the land.

“I’ve always known the general history of the area, but now I’m really turning to learning in a deeper fashion,” she says. “Not enough landscape art acknowledges the history or is working productively towards decolonization. It is time that I do that learning and address that topic.”

Take a look at Sarah Ciurysek’s online gallery

Visit the School of Art

ResearchLIFE

ResearchLIFE highlights the quest for knowledge that artists, engineers, scholars, scientists and students at UM explore every day.

Learn more about ResearchLIFE