Simulation training creates lifelike scenarios for students

For students pursuing careers in health care, the jump from learning in a classroom to working in a hospital can be a daunting leap. The Clinical Learning and Simulation Facility (CLSF), a key component of the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences’ Clinical Learning and Simulation Program, helps to make that transition more comfortable for students.

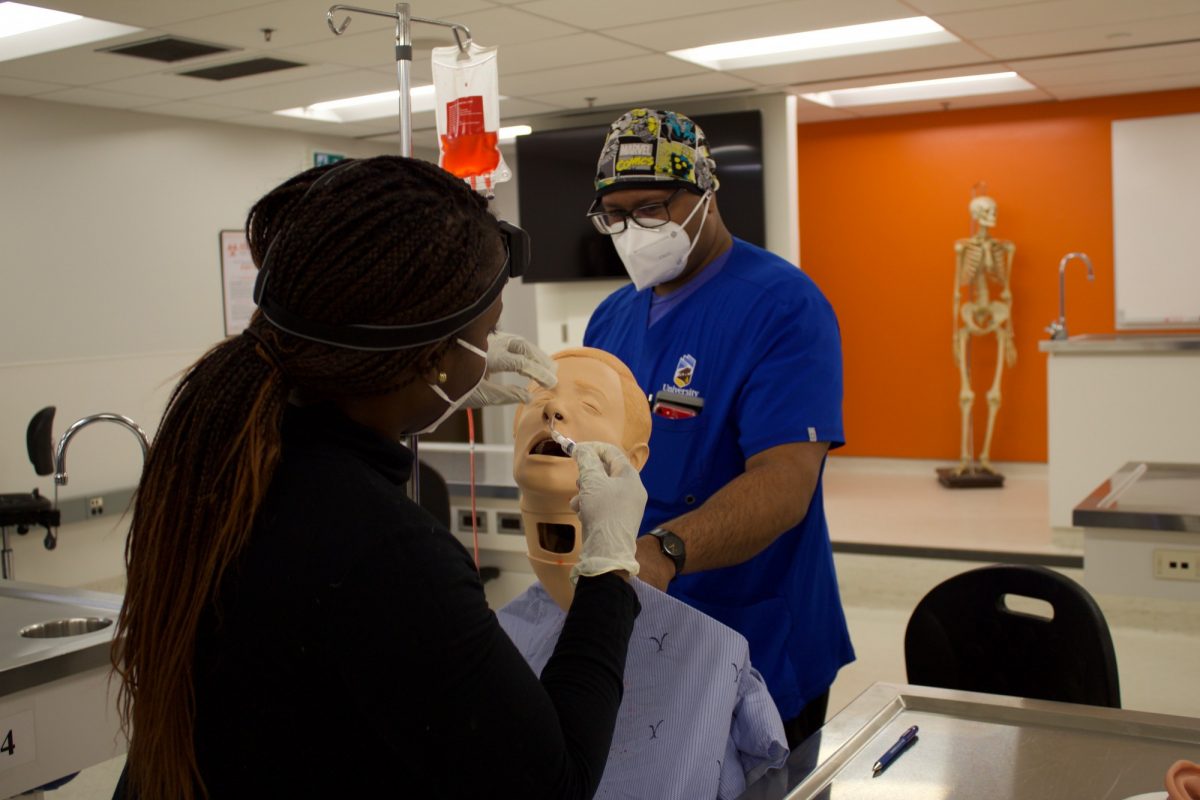

As one of Canada’s most comprehensive simulation teaching facilities, the CLSF, a partnership of UM and Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, is able to simulate realistic health care scenarios for its students. By using robotic manikins that can simulate everything from breathing to a pulse and reflexes, students are able to practice skills they’ve lear ned in the classroom in a more lifelike setting, without jumping into a scenario with real people.

“I wanted to expose our learners [to skills] in a low-risk, low-stress environment,” says Dr. Caroline Kowal who uses the manikins for her advanced skills course in family medicine and emergency medicine residency programs. “That’s where the idea [for CLSF] came from. Over the last three years or so, we’ve just kept adding more creative ideas.”

Educators can’t always buy manikins that simulate the skill they’re hoping to teach, or they may be extremely expensive. Instead simulation technicians and educators work together to figure out how to simulate those experiences with the manikins on hand and adapt with pieces they can create or purchase at hardware stores.

One of the more complicated manikins simulation technician Simon Ovid has worked on is named Kevin, a model that shows an abscess at the back of the throat. The manikin was broken in the back of the head, allowing Ovid to add a jelly surface and red food dye as an abscess.

“I wasn’t sure how this was going to work out, it was a lot of trial and error,” he said.

For her emergency medicine program, Kowal worked with Ovid to simulate a resuscitative hysterotomy procedure, when a pregnant woman has a cardiac arrest and health-care providers have to do an emergency delivery in hopes of saving the mother and child.

Students worked in teams, with some students performing CPR and watching the vitals of the “mother” while others cut through layers of plastic and a beach ball filled with fluid meant to replicate a c-section.

“The students said they felt stressed after, so we were able to kind of reproduce some of that stress level,” said Kowal. “The students really appreciate the opportunity.”

“It shows that the learners are really buying into the simulation,” adds Ovid.

“I want students to be comfortable to perform these [skills] on a real person,” Kowal says. She explains that some of the procedures they practice are rare. Learners and trainees likely will never perform these skills during their career, but if they do, they will be ready and confident. She says last year a past learner performed a something they had practiced in the lab, a lateral canthotomy (an emergency surgery where a ligament around the eye must be removed to prevent vision loss) six months after graduating from their residency program.

“When something like that happens, the [former] learners will sometimes email me like ‘guess what?’” says Kowal. “They’re thankful and they’re so glad that we do this.”

Dr. Delphine Ruremesha, an emergency medicine resident, says training in the sim lab gave her the confidence to treat a Bartholin cyst, a swollen gland near the vaginal opening.

“It’s something where before having the session with the gynecologist and doing the simulation I would have been uncomfortable doing it and referred it out, but now I feel comfortable doing it myself,” she says.