Monument & Spectacle: Envisioning Winnipeg in the 1930s

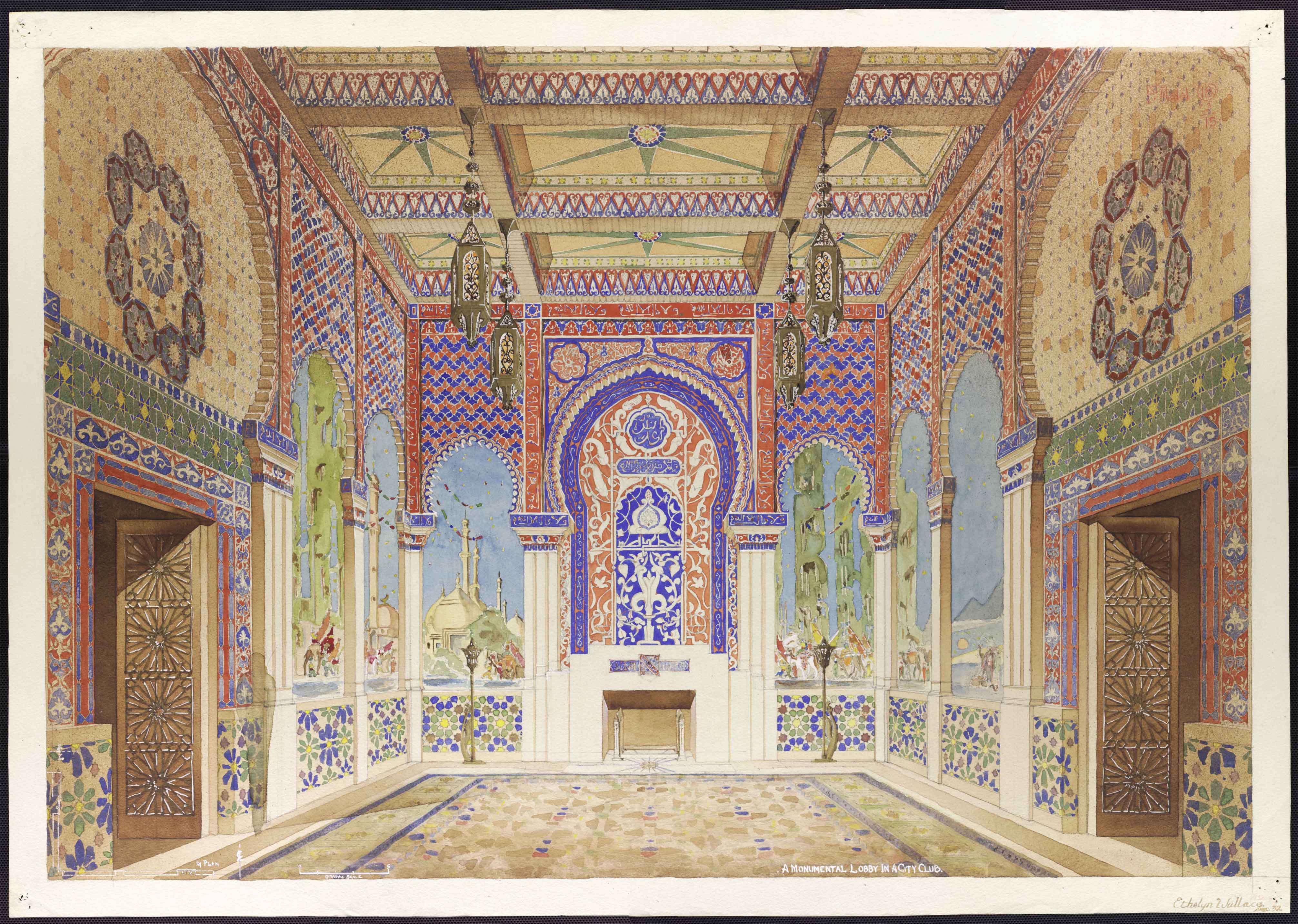

The Gallery of Student Art (GoSa) at the UMSU University Centre recently hosted, from February 18 to March 1, 2019, an exhibition of drawings and watercolor renderings produced in the 1930s by students of the Faculty of Architecture. The aim of this exhibition was to reveal the exquisite craftsmanship of these artworks and to acknowledge the Faculty’s distinguished status throughout the 1930s at the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC). Most of these artworks received First Medal or First Mention at the RAIC competitions. For eight years in a row, between 1930 and 1938, the then Department of Architecture won major awards given in the nation-wide competition, but in 1938, the students were awarded an astounding six out of eight awards! Even though none of the designs were ever built, nevertheless they are notable for their adherence to the prevailing views of the leading and influential architects such as John A. Russell and Milton Osborne, as well as internationally acclaimed architects such as Le Corbusier and Daniel Burnham, among others.

An Era of Crisis and Creativity

What characterizes the period between 1930 and 1939 is socio-economic and political unrest. The Great Depression era and the impending political crisis in Europe triggered a profusion of creative design that not only reflected but also subverted the reality of the local economy and the increasing political unrest. It also attested to the influence of Nazi Germany’s state-totalitarianism and its effect on Canadian national identity. Thus, although many of the designs produced by the students throughout the 1930s incorporated elements from such diverse architectural and artistic movements as Futurism, Art Deco, and the City Beautiful Movement, they also included influences fro m Albert Speer’s designs for Hitler’s Germania (or as we know it, the city of Berlin).

Nazi Germany’s influence on architectural style in Winnipeg originates from the anti-urbanist movement of the earlier decade. Arguably, some of the architects looked toward monumental and utopian architectural praxis to suggest the idea of order and symmetry, simplicity and functionality. Possibly, they looked toward an expression of nationalistic values during the darkest economic times Canada ever experienced, for in the midst of the Great Depression poverty due to unemployment reached unprecedented levels. It needs to be stated that the employment of fascist elements (such as the swastika or eagles) in the students’ designs was almost undoubtedly not a conscious conformity to the Nazi ideology of state totalitarianism and suppression but rather an expression of the vague nationalistic optimism that hovered over the German nation and the world, albeit for a very brief period. It is questionable whether Hitler’s violation of the Treaty of Versaille (1936, 1938) and the subsequent annexation of Austria into the German Empire had much impact on Canadian politics. However, as stated earlier, Winnipeg’s expanding population, consisting mostly of “foreigners” from Central and Eastern Europe, was seen as a problem; therefore, architectural design that expressed order and a return to the classical period is perhaps an expression of imperialistic and colonialist values based on the ideology of British and Western European supremacy, or the ideology of belonging. It is most likely that none of the architects realized the imminent horror as a consequence of this ideology.

Inspiring Civic Pride

Winnipeg architecture students of the 1930s embraced and incorporated the prevailing architectural styles of the first decades of the twentieth century. However, under the influence of John A. Russell, for whom sustainable community development and environmental consciousness constituted the basis of architectural praxis, these aspiring architects turned towards community improvement by embracing the ideals of the City Beautiful aesthetic, or anti-urbanism, championed by Burnham, as opposed to the futuristic architecture inspired by Sant’Elia. The City Beautiful Movement’s focus was on the creation of monumental and spectacular architecture whose purpose was to inspire civic pride, and at the same time, eliminate problems of congestion. Thus, the undisputable success with which the students from the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture at the University of Manitoba fared at the yearly competitions organized by the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada was due to their ability to embrace and effectively incorporate the architectural styles predominant in the first decades of the twentieth century, and at the same time, to look inwardly and address the socio-political concerns that affected their city. Unfortunately, as mentioned earlier, due to the ill-fated times in which the students created their designs, none of the designs were ever realized, yet the students’ visions continue to inspire and probe questions of the complex relationship between communities and buildings.

More ways to see the work

The Piano Nobile at the Centennial Concert Hall will host an expanded “Monument & Spectacle: Envisioning Winnipeg in the 1930s” exhibition from May 9 until May 25, 2019. Concertgoers who have tickets to events will be able to enjoy these works. And for those who are interested in further exploration, there are 167 watercolour renderings and drawings by former students of the Faculty of Architecture from the 1930s alone held by the University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, 330 Elizabeth Dafoe Library. They are open Monday to Friday, 8:30 AM to 4:30 PM and welcome visitors.

Sponsored by the University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections, the Faculty of Architecture, the University of Manitoba Art Collections, the University of Manitoba Students’ Union Gallery of Student Art, the University of Winnipeg Curatorial Practices Program, and the University of Manitoba Libraries.

Student assistance was supported, in part, by the Faculty of Architecture Endowment Fund, with M.Arch student Jessica Piper and Prof. Terri Fuglem, ‘Archiving Historical Student Work.’