March 8, 2021 —

Canada’s Parliament recently passed a non-binding resolution declaring the treatment of the Uyghur minority in China’s Xinjiang province an act of genocide by the Chinese state.

Next year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing have become part of the political debate on how the Canadian government should respond to the Chinese government’s treatment of the Uyghurs.

Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole has called on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to pressure the International Olympic Committee to relocate the Games because sending athletes to a country that is committing genocide would “violate universal fundamental ethical principles.” Human rights organizations around the world have also called for a boycott.

For its part, the Canadian Olympic Committee has said a boycott is not the answer, adding that “the interests of all Canadians, and the global community, are advanced through competing and celebrating great Canadian performances and values on the Olympic and Paralympic stage.”

Overlooked in the boycott debate is the impact on sport by allowing the world’s highest-profile event to be used to “sportwash” a nation’s reputation.

Some athletes oppose a boycott

Some have questioned how an athlete boycott would impact Chinese human rights policies. They argue that a boycott only harms athletes. For most athletes, competing in the Olympics is the pinnacle of their competitive careers.

Exiled Tibetans in India use the Olympic Rings as a prop as they hold a street protest against holding the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. Five effigies represent Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong, Inner Mongolia and the region ethnic Uyghurs call East Turkestan, under Chinese control. // AP Photo/Ashwini Bhatia

Athletes in all sports have had to forgo competitive opportunities as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. After the postponement of last summer’s Tokyo Games, no group of athletes has been more negatively affected than Olympians.

Athletes are not a single-minded, apolitical mass. Some do not want to sacrifice the opportunity they have worked toward for much of their elite competitive career. And some have expressed their desire to separate sport and politics.

Mixing politics and sports

Concerns about China’s human rights record over the treatment of Tibet were also expressed when Beijing hosted the 2008 Summer Olympics. At the time, then-IOC President Jacques Rogge reiterated the long-standing position that such “politics” have no place in the Olympics.

Canada’s flag-bearer at the 2008 Summer Olympics, kayaker Adam van Koeverden, publicly opposed any talk of protests over China’s human rights policies. Van Koeverden is now a Liberal MP and the parliamentary secretary for Canadian Heritage for Sport — he voted in favour of the genocide resolution, but still opposes an Olympic boycott.

But to assume that all athletes feel sport and politics should be separate is to ignore the powerful developments of the past year, when athletes played a prominent role in Black Lives Matter and #MeToo-inspired protests.

While the Olympic movement’s origins celebrate international good will, education and intercultural understanding, modern sport has been “political” since it emerged in the late 19th century.

Those who controlled sports events determined who could participate, who could not (quite often women, working classes, Indigenous Peoples and people of colour) and under what rules — such as celebrating amateurism’s “sport for sport’s sake” mantra while denying talented athletes an income commensurate with their skills.

Olympics no stranger to politics

The Olympics has long also been embroiled in international politics.

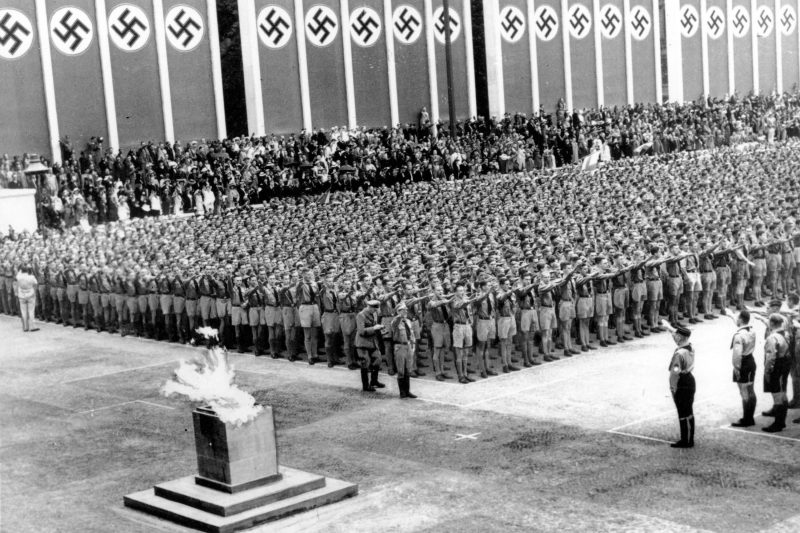

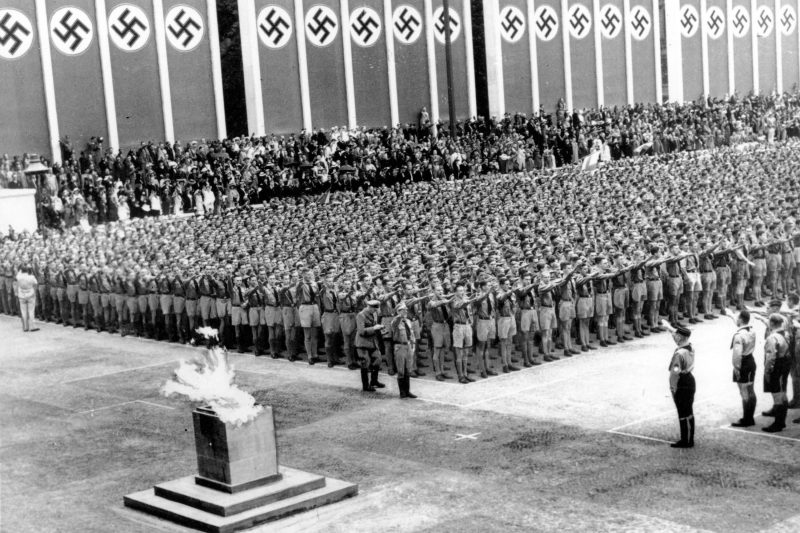

The 1936 Games in Nazi Germany, itself subject of heated boycott debates, is the most oft-cited example.

Many athletes whose convictions prevented them from competing in Berlin travelled instead to Barcelona for an alternate “People’s Games,” which never moved beyond the opening ceremonies following the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

German Nazi soldiers line up at attention during the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin. Some athletes boycotted the Berlin Olympics in an early example of athletes taking a political stand. // AP Photo/File

In an era of decolonization, some leaders of developing nations opted for their own multi-sport event in 1963: the short-lived Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO).

Initiated by Indonesia, GANEFO was an attempt to provide athletes from newly decolonized nations with an alternate to the Olympics. Organizers overtly integrated the politics of anti-colonialism and the non-aligned movement into the event’s messages. Stern opposition was expressed by both the IOC and the U.S. State Department (whose citizens were not involved) and international sporting bodies suspended those athletes who participated in GANEFO.

Not all boycott actions are created equal. Geopolitical disputes managed by state governments differ from grassroots social movements challenging established power structures.

Soviet boycott of ’84 Games

The Soviet bloc’s boycott of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics — a diplomatic rejoinder to the West’s boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan — was very different from the movement to boycott sport competitions against South African cricket and rugby teams in the apartheid era. The latter, however, did contribute to an Olympic boycott, when 22 African nations refused to compete at the 1976 Montréal Games over the presence of athletes from New Zealand, a country that had been targeted by protesters for continuing to schedule matches against all-white teams from South Africa.

The 2022 Winter Olympics were controversial even before Beijing was picked as host city.

No Olympic bidding cycle drew as little interest as 2022, with major winter sport cities such as Oslo withdrawing bids in the face of opposition from its citizens. The IOC was left with only two candidates — Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan — leading Human Rights Watch to warn that “major sporting events are also accompanied by human rights violations when games are awarded to serial human rights abusers.”

Rogge may have asserted in 2008 that “the Olympic Games are not the place for demonstrations.” But the IOC’s position overlooks other alternatives. There are alpine hills, arenas, bobsled tracks and other facilities — many of them built for previous Olympics — in many winter sport destinations. Olympians could still compete if a decision was made to move the Games from Beijing.

Presuming, as van Koeverden did in 2008, that having the Games in China will not “contribute to their problems or make them any worse” only entangles the Olympics in the very politics it seeks to avoid.

It becomes harder for the IOC to stake a claim to an apolitical high ground if it allows the Chinese government to “sportwash” its treatment of Uyghurs by showcasing sporting events in an effort to obscure the events unfolding in Xinjiang.

This article from Russell Field (Associate Professor, Sport and Physical Activity) originally appeared on The Conversation. It appears here under a Creative Commons licence.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.