‘We are punching above our weight, that’s for sure’

The U of M’s chemistry department, with 145 undergraduate students, is middle-of-the-road in terms of size, but it’s educating students to such a high calibre that it is a juggernaut on the national stage: The department claims, for example, a Nobel Laureate and two Banting Fellows. All fairly recent. What’s going on?

“We are punching above our weight, that’s for sure,” says Phil Hultin, chemistry professor. “Ever since I joined the department 20 years ago I’ve always had the sense that we were punching above our weight, and I’m proud of us, and we may not be noticed by many but the Banting awards have definitely shone a light on us…. I’m thinking there are not many chemistry departments in Canada who have produced two Banting students.”

Indeed, according to the Vanier-Banting Secretariat, no other chemistry department has produced more than one at the doctoral level.

The “Banting students” are Drs. Vladimir Michaelis and Laina Geary. Michaelis was supervised by chemistry professor Scott Kroeker and is now a postdoctoral fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Geary was supervised by Hultin and is now at the University of Texas at Austin. Both of them completed their undergraduate degrees and PhDs in the Parker building.

“We formed these people,” says Hultin. “We make sure you get a damn fine education in chemistry. We really care about the education they get and we offer challenges that may not be offered in other places. My colleagues and I have a habit of holding particularly high standards for third- and fourth-year students, even second-year students.”

Canada’s three research-granting councils (the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada) administer the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowships Program. The Fellowships are valued at $70,000 per year for two years.

“Vlad is a very ambitious young man,” Professor Kroeker says. “He is highly motivated and extremely efficient. I took him on as an undergraduate student for a summer and it quickly became apparent that he had much bigger ideas than the little project I gave him…. He now leads a materials subgroup in [Bob Griffin lab’s at MIT] and is beginning to look for faculty positions in Canada and the US. The Banting fellowship will give him greater freedom to explore his own research directions at MIT and establish himself further as an independent researcher.”

Geary grew up in Sanford, Manitoba, and came to the U of M study in the Faculty of Science. After taking time off after her first year, she realized she had a keen interest in organic chemistry. She returned and started to work with professor Hultin. Years later, as a graduate student in Hultin’s lab, she developed a completely new research project that eventually became her doctoral thesis. When Geary and Hultin published the results, one of the papers made the cover on the

European Journal of Organic Chemistry, and the second paper was chosen by the editor of the Journal of Organic Chemistry as a Featured Article. That article became one of the 20 most accessed papers in 2010.

In 2011 when she won the Banting Fellowship, Geary was asked about her experience at the U of M’s chemistry department. She said: “The Department has so many excellent teachers and mentors, and I had a lot of support from all levels throughout both my degrees. I received a first-rate undergraduate education at UM, and that inspired me to go to graduate school. I had completed a fourth-year honours project with Phil, so staying at UM to complete a PhD with Phil was an easy decision. As an undergraduate, Phil taught me how to effectively run experiments, but more importantly, as a graduate student, he taught me how to be a scientist. For this, I know I received an excellent graduate education at UM as well, and I am grateful.”

As for the Nobel Laureate, that honour was given to alumnus Scott Cairns who graduated in 2001. As a military kid who moved often in life, Cairns found a sense of community in a rather odd spot: the basement of the U of M’s Parker Building. Here, he served as president of the Chemistry Club. Twelve years later, in the summer of 2013, you’d find Cairns in war-torn Syria leading a team of chemical inspectors with the United Nations’ watchdog investigating allegations of chemical attacks. This group, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), and its members won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2013, and Cairns was also awarded the 2014 U of M’s Distinguished Alumni Award (Professional Achievement). (Nominations for the 2015 DAA close Nov. 18.)

Intriguingly, the department’s small-ish size (U of T for instance counts 449 chemistry undergrads, while U of A only 120) allows it to groom young students to an unmatched degree, but as they mature and move into graduate studies, talented though they are, our smaller graduate program currently hinders their ability to collaborate with peers, sharing ideas and expanding research projects.

“The main problem we face is persuading top undergraduate students to study at U of M for graduate work,” chemistry professor Scott Kroeker said. “Overall, I am not at all surprised that our students go on to earn prestigious fellowships. If we were more effective at recruiting the best students, success stories such as these would multiply!”

Attracting and retaining top graduate students is a strategic priority of the U of M, as outlined in its draft 2014 strategic plan. And a priority of the newly announced Front and Centre comprehensive campaign is graduate student support.

The fact that the department currently has a small graduate student population means that their supervisors are more discerning, since they invest a lot in their students.

“Graduate students could be better served by having more peers, sure,” says Hultin, noting that professors at U of M generally have about two to four students whereas faculty in some other chemistry departments may have four to 10. “It changes the dynamic considerably because you need a critical mass to have ideas really flourish. We have the talent and we can foster it, but the next level of it is to increase our graduate student numbers. In any case, when you have a small number of students you pick carefully, and you put a lot into them, and you get results.”

To support the students the U of M’s chemistry department has worked hard over the past decade to establish a versatile array of instrumental infrastructure, and students leave with an education that meets or exceeds that of other institutions, Kroeker says.

“I often receive reports from former students that their chemistry courses from U of M equipped them very well for the challenges of graduate school abroad. This is partly due to the conscious emphasis we place on mentoring upper-level students in advanced chemistry and research. The environment in our department is very supportive and cooperative, with faculty members working closely with undergraduate and graduate student researchers. This is to be contrasted with some larger chemistry departments which adopt a more competitive, ‘sink-or-swim’ approach,” he says.

“[We are] limited only by our imagination.”

A brief history

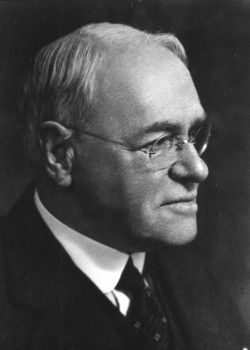

The Parker Building on the Fort Garry campus is named after Dr. Matthew Archibald Parker, who died 61 years ago.

As the Manitoba Historical Society notes, Parker was born in Scotland in 1871 and he and his family moved to Winnipeg in 1904. In 1911, Parker became Professor of Chemistry at the University of Manitoba, making him one of the first six science professors hired by the University (the others were Frank Allen, Physics; Gordon Bell, Bacteriology; Reginald Buller, Botany & Geology; Robert Rutherford Cochrane, Mathematics; and Swale Vincent, Physiology and Zoology).

For many years Parker was not only the sole chemistry lecturer at the U of M, he was also the only trained chemist in Manitoba at the time. As such, Parker served as the Provincial Analyst for a number of years and toured the province lecturing on the subject.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.