Boys playing hockey at the McIntosh, Ontario, school. Many students, like Eugene Arcand who will speak at the U of M, said that they would not have survived their Residential School years were it not for sports. // Image: St. Boniface Historical Society, Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Manitoba Province Fonds, SHSB 29362.

Reconciliation through sports, a public forum

Eugene Arcand and the boys from his Residential School’s hockey team took the tape off their sticks and heated it a bit over any source of heat they could find. They did it to make the glue sticky again so they could reuse it to tape shin pads to their legs. Supplies were always tight. They never wore new equipment. And making it on the team was a brutal competition because every boy and girl knew playing sports at a Residential School allowed for a marginally better life – a way to leave the oppressive institution’s grounds, to eat better, to have a semblance of childhood even though the hellish reality of Residential School life followed them everywhere.

Sport provided them with an outlet, though, a path to something else. In a new open forum, the Faculty of Kinesiology and Recreation Management will explore how this path can lead to Reconciliation.

The inaugural Sport & Reconciliation Gathering, which runs Feb. 21-23, will ask and answer how we can achieve the Truth & Reconciliation Commission’s nine Calls to Action related to sport (#87 – #91) and education (#62-#65).

The inaugural Sport & Reconciliation Gathering, which runs Feb. 21-23, will ask and answer how we can achieve the Truth & Reconciliation Commission’s nine Calls to Action related to sport (#87 – #91) and education (#62-#65).

Arcand will be among the speakers and UM Today asked him for a preview of his talk.

UM Today: What will you speak about?

Eugene Arcand: First of all, I want to commend the University of Manitoba for taking the initiative to address the Calls to Action especially in this area, which was a major saviour for many of us who went to Residential Schools.What I’m going to talk about is living examples of how sport basically was our outlet. It was our sacred space. The missionaries liked to show of the mission kids, and it didn’t take very long for most of us to realize and recognize that if you were one of those kids that got to travel on the sports teams to various local towns and tournaments, that it was first of all, a safer space than being in the residence area, plus you got fed better. You got treated better for the time that you were on these teams. And that included pretty well every sport, but I’d say hockey, for the boys, was probably the most important. But it required us to be all around athletes in order to stay on those teams, so that included things like track and field—soccer was a big sport where I was at Duck Lake.

I was at St. Michael’s school for nine years, from 1958 till 1967. And I was in Lebret from 1967 until 1969. A total of 11 years. But even in Lebret, sport was the saving grace for me personally, and for many others.

So did it provide you with a means of escape from the realities of Residential School or did those still follow you onto the rink?

It was a safe space. When I talk about escape, I mean running away.

Did you ever think about or try to run away when you were on a sports trip?

That’s part of my speech. Certainly, we all at some point in time contemplated running away. Many of us tried to. But you get caught and the punishment was just horrific. So when we were on these excursions, for most of us, we didn’t know anything else. For us, it was a good space. If we could get on that team, it was good enough for that point in time. If you run away while you’re on one of those excursions, you’d never get taken again, right?

What sports did you play?

My sports were hockey and fastball. And soccer. At that time in my life, growing up, the competition was fierce within the school to get on those teams. There were times we’d injure one another so the other kid couldn’t go, you know. And then you’d get moved up. It was survival mode, right? For me, I didn’t look forward to playing in the NHL. That wasn’t the goal. My goal was to get on that team and get the heck out of there every chance I had. And also to be a big boy so no one would bother me anymore. Those daily threats of psychological, physical, sexual, emotional abuses were absent during those times.

That’s what sports meant to you then. Has it changed at all now that you’re older?

When I came out of those institutions in 1969, sports still played an important part of my life. A very, very important part of my life because it was the only thing I knew. For me, I didn’t have any carpentry skills. I didn’t have any farming sills. I didn’t have any skills other than sports.

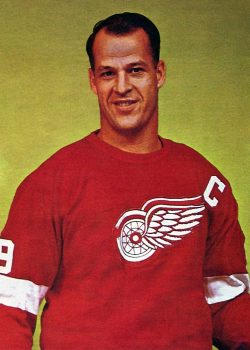

And the other part, for me, was I had no idea how good I was. All I knew is I had to be good enough to get on the team to get out of Residential School. And when I got out, I kept playing and the other coaches would ask me where I learned to play soccer or hockey. I started to realize I was good, and sport took me around the world. I used to dream of meeting guys like Gordie Howe. I did eventually meet him, and ended up spending a lot of time with him. I have some good, funny stories of me and Gordie, but that’s for another time.

What are you hoping people take away from the event?

I’m happy the U of M is opening this space because there are a lot of young Indigenous people out there that are excellent, excellent athletes. And they’re held back by poverty and held back by systemic barriers that include racism and prejudice.

I have been with the North American Indigenous Games since 1990, and I see raw talent. I see raw warrior spirit wanting to compete, to showcase their skills. But there are barriers.

And the U of M is running programs to identify and recruit Indigenous athletes. This is long overdue. And in this case it’s partnering up to address the Calls to Action from the TRC’s final report. And I applaud anyone who looks into options to accommodate – and appreciate – these young people who are overlooked and are statistics in many other forms of their lives. But post-secondary education sports can be a stepping-stone, or a place to land.