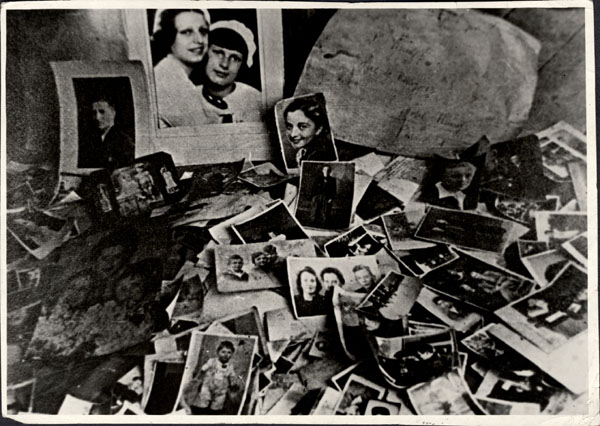

Photo from The Sovfoto Archive. Courtesy of the MacLaren Art Centre.

Photrocity: Mass Violence and Its Aftermaths in the Sovfoto Archive

A collaboration between the University of Manitoba’s School of Art Gallery and Barrie, Ontario’s MacLaren Art Centre, Photrocity is curated by Adam Muller, professor, department of English, film and theatre, Faculty of Arts.

The exhibit at the School of Art Gallery opens formally on July 15 at 7:00 p.m. and will run concurrently with the 2014 meeting of the International Association of Genocide Scholars conference at the U of M from July 16 to 19. It remains available to audiences through October 31, coinciding with the formal opening of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg in September 2014.

They left Lvov in a hurry. The first leg was on foot, the second by horse cart because the train was dangerous, apt to be searched. He remembers nothing until the fishing boat whose gunwales sat scarcely above water by the time they set out – the only time he would ever be undersea. Foot, cart, boat, ship – like a parable.

Four years later, in the new world Sol, the second-oldest, will be given the birth certificate of his brother who died. Better to be born here than there. That brother, the first Sol, is born without a heart. Their mother, hands held to her throat in her purest gesture of despair, raves about the boy from Lvov who astounds his doctors by being born two-hearted. Later, in the hospital, dialysis unit humming by his bed, shadows whirling on the wall, Sol thinks: He and I. He and finally I.

— text by Struan Sinclair

Photrocity makes use of images of atrocity to alter its audience’s understanding of shared aspects of human suffering caused by mass violence during wartime. The exhibit contains 19 photographs from the Sovfoto Archives — state-sanctioned photographs from the Soviet Information Bureau dating from 1936 to 1957 — and associated, specially-commissioned text fragments by the writer Struan Sinclair.

The juxtaposition of text and image is designed to heighten viewers’ emotional engagement with the photographs while encouraging them to reflect more deeply on links between past and present instances of the harms they depict.

UM Today spoke with exhibition curator Adam Muller.

You’ve done scholarship on the representation, images and propaganda of war and mass violence. Could you say a little more about this exhibit in terms of that work?

Muller: Photrocity arises from the overarching questions underpinning my current research, which are: How, and how well, do our representational languages and strategies convey the substance of genocide and mass atrocity. Where and how do atrocity representations succeed in providing insight into the experience of unimaginable violence, and when do these representations fail? This question is also fundamental to [the project] Embodying Empathy, which is seeking to identify a way of representing the often atrocious experience of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools to diverse audiences including survivors, intergenerational survivors, and secondary witnesses who may not be Aboriginal or know much about the history of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples.

Given that the images are from a large archives of Soviet propaganda, what was the criteria by which you curated and shaped the photo exhibit?

Muller: The photographs selected for exhibition in Photrocity are the ones that in my opinion are some of the least straightforward and the hardest to understand in the Sovfoto Archive. Some images are intended to present a specific fact or facts, but in their occlusion of other facts they end up meaning something else entirely. Some of the images have been hand-altered by Soviet censors, often very strangely, and always to convey a point the unaltered image might not have been able to sustain. And many of the images are beautiful, forcing viewers to confront the tension between aesthetic pleasure and moral outrage and disgust. A couple of the images were originally taken by the perpetrators of atrocity, obliging us to think about ways to escape or thwart the photographer’s desire that his viewers see the world, and his victims, as he does. The photographs were also selected to show different phases of official Soviet discourse on World War Two. As a result they can be seen early on attempting to mobilize popular support for total war and ongoing military support from allies like the United States. Later on they can be shown attempting to cast the Soviet occupation of countries like Poland as beneficent in anticipation of the formation of the Eastern Bloc and ongoing Soviet regional dominance.

What’s your hope for the impact or effect of the photos/texts on visitors to the exhibition?

Muller: I would hope that visitors to Photrocity would come away from the exhibition troubled by what they see, in the sense that they might be able to more clearly appreciate the difficulty of giving form to unimaginable violence. I also hope that visitors are moved to sympathy for the many victims shown in the Sovfoto photographs. In conjunction with a reading of Struan Sinclair’s beautifully haunting narrative fragments, the experience of viewing Photrocity’s images is intended to encourage visitors to think more deeply about the various aftermaths of mass violence, in the past as well as the present.

The Sovfoto Archive

The Sovfoto Archive at the MacLaren Art Centre comprises 23,116 vintage gelatin silver prints dating from 1936 to 1957, all originating from New York-based press agency Sovfoto/Eastfoto. This collection has a particular focus on World War II and its aftermath, as well as Soviet life in the pre-war and post-war periods. Far-reaching in scope, this archive includes series on rebuilding Soviet cities after the war, the emergence of collective farms, Soviet education, theatre and the arts and other diverse subjects.

Established in 1932, Sovfoto received state-sanctioned photographs from the Soviet Information Bureau (Sovinformburo) on consignment. Photographs were selected, often retouched, and appended with English captions, all before leaving the USSR. Sovfoto, in turn, sourced these images to a wide-ranging number of North American clients.

These photographs were the only significant source of visual reportage of Soviet life after the iron curtain ended the free flow of information between the Soviet bloc and democratic nations. Sovfoto later became Sovfoto/Eastfoto, and continues to operate under that name as a major and growing stock photo agency of historical and contemporary photographs from China, Russia, and other former and current communist nations.

The School of Art Gallery acknowledges the assistance of the MacLaren Art Centre in bringing this exhibition come to fruition. Thanks are also to the University of Manitoba’s Faculty of Arts Department of English, Film, and Theatre and Department of German and Slavic Studies, the International Association of Genocide Scholars, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for their generous support of this exhibition.

[rev_slider Photrocity]

Photrocity: Mass Violence and Its Aftermaths in the Sovfoto Archive

School of Art Gallery

Tuesday, July 15 – Friday, October 31, 2014

Reception: July 15, 7:00 p.m.

For more information about the exhibition, contact:

School of Art Gallery

204.474.9322

gallery@umanitoba.ca

School of Art Gallery

255 ARTlab, 180 Dafoe Road

Gallery Hours

Monday – Friday, 9:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m.

Closed August 4, September 1, October 13

Parking

ARTlab is located on Dafoe Road next door to Taché Hall and Drake Centre. Nearby parking.