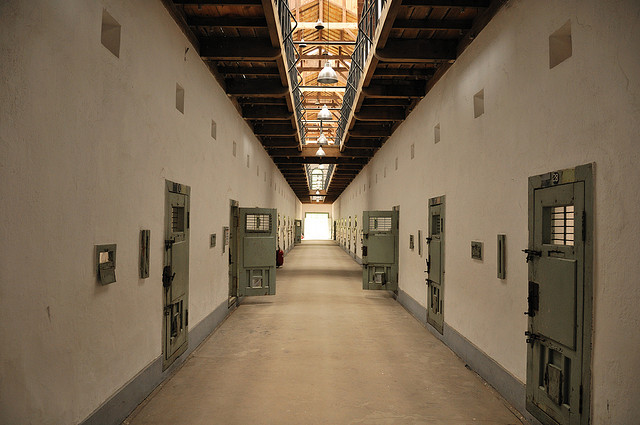

Photo: Christian Senger

Op-Ed: Cruel and unusual punishment: It’s time to end solitary confinement

The following is an op-ed written by Debra Parkes, associate dean in the Faculty of Law. It was originally published in the Globe and Mail on June 6, 2016.

Canadians are hearing a lot more about solitary confinement in this country’s prisons, jails and immigration detention centres. Finally, hard questions are being asked about this practice which we know is harmful, inhumane, and used disproportionately on prisoners with mental disabilities, those who are Indigenous or black, and women. Prompted by increasing attention from the media, courts, oversight bodies, and medical professionals, governments are being forced to respond, although the practice of solitary remains entrenched.

Each year, thousands of prisoners are held in a form of solitary confinement called administrative segregation. They are isolated in a small cell for 23 hours a day, not for punishment, but for some other reason – they are suicidal or self-harming; they are at risk from other prisoners; or they are difficult to manage for any reason. We do not have exact numbers because most provincial and territorial governments still do not release information about their use of solitary confinement, notwithstanding calls for transparency and accountability.

Despite its widespread use, there is nothing natural or commonsensical about isolating people who are at risk, acting out, or experiencing mental illness. Like slavery was in its day, solitary confinement is a normalized, inhumane practice, on which we will one day look back and wonder why and how it was tolerated for so long.

In the last year and a half, lawsuits have been filed in both British Columbia and Ontario alleging that the law, policy and practice of segregation in federal prisons systematically violates numerous Charter rights including equality and the right against cruel and unusual punishment. Those suits call for time limits on its use, external oversight, protections for prisoners with mental disabilities, and judicial authorization for long-term segregation. Separate class action suits seek damages for youth detained in solitary in Ontario and adults confined to solitary in federal prisons.

At the same time as this litigation is commencing, the federal Correctional Service is reporting a substantial drop in its use of segregation, suggesting that the practice has been overused and is often unnecessary, even by corrections’ own terms. Meanwhile, the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies charges that the reported numbers do not truly represent fewer prisoners in isolated conditions, particularly women, but rather a renaming exercise for conditions of effective segregation.

In the provinces and territories, there remains much indifference to calls for accountability, even basic transparency. However, at least in Ontario, things may be changing. In March 2015, the provincial government announced a comprehensive review of the use of solitary.

The way forward is not reforming solitary, but committing to end it altogether. Speaking in Ottawa last week, former Supreme Court Justice Louise Arbour reflected on the 20 years that had passed since she led a commission of inquiry into illegal uses of force and solitary confinement at the Prison for Women. In 1996 she issued her report calling for hard limits on the use of segregation (no more than 60 days in a calendar year) and judicial oversight.

Ms. Arbour said that if she was doing it again, and given what we now know about the harms of segregation and the failures of reform efforts, she would call for an end to the practice. Earlier this year, the Ontario Human Rights Commission urged the Ontario government to do just that, sketching out a framework for developing more humane alternatives that meet public safety imperatives.

There is no easy fix, but to start, substantial research shows that dynamic, human interventions do more to reduce tensions and keep prisoners and staff safe, than does isolation. People with significant mental health disabilities should receive the care they need in a community or hospital setting, not in prison.

People who might harm others need interventions to address those behaviours, not isolation which exacerbates them. It is in our collective interest to not have people emerge from prison more damaged and dangerous than when they went in.

Ending solitary confinement requires a shift in our thinking, a collective facing of the facts. It entails a recognition of prisoners’ basic humanity and that imprisonment itself creates many of the harms and pathologies that are used to justify confining people to tiny cages without human contact, from which they emerge more damaged.

If governments do not act soon, courts should. The Charter right against cruel and unusual treatment or punishment is becoming a weightier tool in the arsenal against inhumane prison conditions.

For example, last month a judge in Ontario awarded damages of $85,000 to two prisoners, ruling that this right was violated by regular lockdowns at the provincial jail where they were detained. A court ruling that administrative segregation amounts to cruel and unusual punishment would be a significant step for human rights and the evidence in favour of such a finding is mounting.

It is time to put a stop to this barbaric practice. Locked up in a windowless cell for 23 hours a day, every day is worse than the death sentence. It is inhumane.

The coverage on this issue is so very one sided. Why does the media choose to ignore or at least not report the fact this is a much more complicated issue? If the general public was faced with the decisions that Corrections staff face every day I’m positive the outlook would change. Also the fact that a high percentage of the time inmates actually “check in” to segregation voluntarily to avoid paying back debts etc… If you’re going to cover a story please be responsible enough to cover all sides.