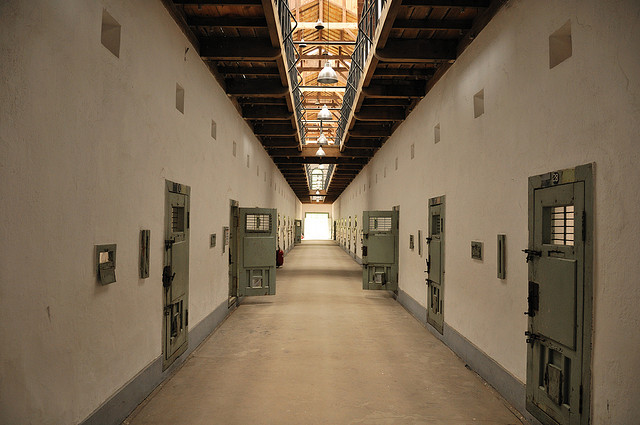

Image: Christian Senger, Flickr

Analysis: Solitary confinement in Canada is a human-rights crisis

Dec. 10 was Human Rights Day, and December is Human Rights Month, and in honour of that we publish an Op-Ed written by Debra Parkes, an associate professor and the associate dean (research) at the U of M’s Faculty of Law (Robson Hall).

Media attention surrounding the deaths of Edward Snowshoe and Ashley Smith, who spent months or years in solitary confinement, is making it increasingly difficult for Canadians to ignore this human-rights crisis.

The damaging effects of solitary confinement (or segregation, as it’s called in Canada) are well known. A United Nations body recently called for states to prohibit solitary for young people and people with mental illness, indeed, for anyone for more than 15 days. Yet segregation is widespread in Canadian prisons. Its use is normalized, routine and increasing, with no enforced limits.

Last month, the Canadian Medical Association Journal published an editorial calling for an end to solitary confinement, noting that elements of psychiatric damage – anxiety, depression, perceptual distortions, paranoia and psychosis – are often evident after even a few days in solitary. Some of these effects can become permanent, particularly when the isolation is prolonged. Solitary exacerbates pre-existing medical conditions and creates new ones, including insomnia, anorexia and palpitations. The damage contributes to a variety of harms: self-injury, lashing out at correctional staff and other prisoners, suicide, inability to cope in society upon release. Solitary is harmful and counterproductive to public safety.

Given this mounting evidence and the growing consensus that solitary confinement violates basic human rights, why is it being employed so widely in Canada? And perhaps more importantly, what can be done to reverse this trend?

Annual reports of Canada’s Correctional Investigator, along with a host of other studies in the federal context, show that the vast majority of segregation placements are for “administrative,” not disciplinary, reasons. Solitary confinement is a tool of population management and its widespread use hinders the development of more productive means of making our institutions and communities safer.

…records obtained through Access to Information in Manitoba revealed many provincial segregation placements for which no legal justification was recorded or where the reason was said to be “overflow,” a basis not authorized in law.

At the provincial and territorial level, we know little about the extent and reasons for solitary because information about the practice is generally not made public. However, records obtained through Access to Information in Manitoba revealed many provincial segregation placements for which no legal justification was recorded or where the reason was said to be “overflow,” a basis not authorized in law.

At a basic level, solitary is widely used because no one is compelling correctional authorities to do anything different. In provincial and territorial systems where independent oversight is limited, there is no incentive to change, particularly as prison populations keep growing under tough-on-crime legislation. Federally, there is no shortage of reports documenting the damage done by solitary and chronicling the failure to act on the many recommendations for reining in the practice made by task forces, commissions of inquiry and other independent bodies.

What we do not need are more correctional rules and policy around segregation. As Justice Louise Arbour wrote in her 1996 inquiry report into unlawful uses of force and prolonged segregation at the Prison for Women in Kingston, “the rule of law is absent, although rules are everywhere.” The Globe and Mail’s investigation indicates that correctional law and policy concerning segregation were breached in Edward Snowshoe’s case, as they were in Ashley Smith’s.

What is needed then is independent external oversight and enforcement of existing law and rights. An important first step would be for Canada to ratify the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture, which would require Canada to have a “national preventative mechanism” to inspect all places of detention to ensure compliance with international human-rights standards. This would provide a measure of accountability and information to the public about the use of solitary confinement and other practices that have human-rights implications. Britain’s Prison Inspectorate performs such a function and Canada’s failure to take this step is troubling.

But beyond transparency and accountability, Canadians are entitled to expect that the rule of law will run behind prison walls. At a minimum, segregation decisions should be subject to independent adjudication.

In the absence of political or institutional will to address this, change may come from the courts. No Canadian court has yet heard a systemic Charter challenge to the normalized use of solitary in the light of the substantial evidence of its negative effects. However, recent cases signal change. Judges in British Columbia and the Northwest Territories have found that the prolonged segregation and other inhumane conditions of confinement experienced by prisoners awaiting trial amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. In one case, the man’s ultimate sentence was substantially reduced to account for the Charter violation. Correctional authorities have settled other cases, including one challenging a regime of segregation specific to women prisoners that had a particularly negative impact on indigenous women.

Rather than waiting for courts to step in, correctional authorities can act on the many recommendations already made, including (to take just one) finding alternatives to segregating mentally ill prisoners.

This human-rights crisis behind prison walls implicates us all, as does the broader problem of which it is a symptom: packed, warehouse prisons that result from punitive policies implemented in the face of evidence of what works to address crime. Hopefully it will not take the death of another Edward Snowshoe for us to begin to reverse this trend.

This article was originally published in the Globe and Mail on Dec. 9, 2014.