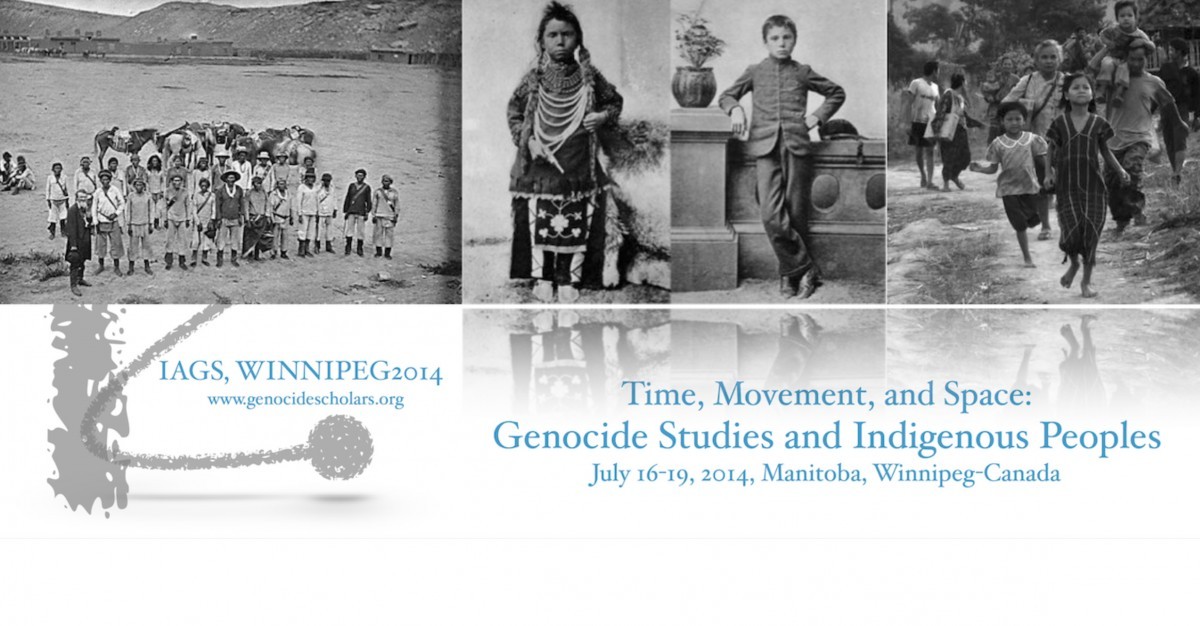

Genocide of Indigenous peoples is focus of international conference

Genocide scholars from around the globe are gathering at the University of Manitoba to explore the genocide of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and beyond. Presentations by keynote speakers and over 100 scholars, artists and activists tackle the difficult truths and lasting legacies of colonial control over, expansion into, appropriation and settlement of Indigenous territories.

“International scholars will discuss genocide as an ongoing, global threat, with particular attention to the plight of Indigenous peoples who face the threat of collective destruction,” says conference organizer and University of Manitoba sociologist Andrew Woolford. The conference, Time, Movement, and Space: Genocide Studies and Indigenous Peoples, runs from July 16 to 19.

“These conversations will include consideration of genocide in Canada and offer insights into how Canadians can grapple with colonialism in this country.”

Most sessions will be open to the media, including some that explore the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda 20 years ago. The full schedule is available here. The University of Manitoba School of Art Gallery is also hosting a public exhibition titled Photrocity, and the Graduate Students’ Association lounge (Room 217, University Centre) will feature presentations by artists on representing genocide.

UM Today caught up with Andrew Woolford to ask him about this large conference.

How did you come to the topic of this year’s conference and why do you think it’s important?

The Executive Board of the International Association of Genocide Scholars was quite clear that the conference theme should reflect upon the plight of global Indigenous peoples. This was great news for the local organizers, since we felt Winnipeg, as a historical meeting place for Indigenous peoples, is well suited to host a conference that reflects upon Indigenous genocides and their aftermaths. Of course, a good conference theme also provides overarching concepts for discussion, and we felt that time, movement, and space (or territory) had crucial roles to play both in attempts to destroy Indigenous peoples, but also in Indigenous resistance.

What surprised you about the entries or the way the theme developed?

I am pleasantly surprised to see so many young Canadian scholars engaged and doing cutting edge work on Canada — the history of Canadian settler colonialism, its ongoing consequences for Indigenous Peoples, and the prospects for commemoration, decolonization, and redress. This conference is an opportunity to show scholars from all over the world how vibrant Canadian scholarship is.

Can you identify three highlights from the conference?

Our excursion to Turtle Lodge on the Sagkeeng Nation will be the first highlight. One hundred of our scholars will go by bus to Sagkeeng on Wednesday, stopping first at the cemetery where residential school Survivor Theodore Fontaine will tell us a little about some of the people who are buried there. Next, we will spend a day at Turtle Lodge, where Elder David Courchene and others will introduce us to aspects of Anishinaabe culture as a living and active resource for Sagkeeng healing and resistance. We wanted an event that would focus not only on destruction, but also on the resilience of Indigenous communities.

Second, our opening event on the evening of Wednesday July 16 will feature the Bolivian viceminister of decolonization, Felix Cardenas, and well-respected Yale historian, Ned Blackhawk. We are quite eager to learn more about the role in government of a viceminister of decolonization.

Third, our other two keynotes are quite exceptional. Tony Barta, who presents on Friday, is the person I would credit with really initiating a serious scholarship of colonial genocide. In his case, Australia, where he lives and teaches, is the focus. We also invited Amy Lonetree, a Shoshone historian, who has done wonderful work on decolonizing museums. Given the impending opening of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, we believed hers is a very important voice to include in the discussion of how the CMHR will represent Canadian attempts to destroy Indigenous peoples.

How has genocide scholarship evolved?

When I presented at an IAGS conference in Sarajevo in 2005, my paper was the only one to consider the issue of genocide in Canada. In Sienna last year, in contrast, there were several papers. This year, of course because there are Winnipeg, there are numerous papers on this topic. Scholars and the public are becoming aware that the definition of genocide, whether that provided by the United Nations or Raphael Lemkin (who coined the term), is not simply a reflection of the very distinct and horrific events that transpired in the Holocaust. There are many different ways that groups, as entities that provide value to their members, can be placed under threat of destruction — and genocide typically involves multiple such techniques operating in a coordinated plan to eliminate a group, but each genocide takes very specific shape.

Are there any conference events that are open to the general public?

This conference is for members of IAGS, so all participants must be registered members and pay a conference fee. These fees allow IAGS to survive as an association and allow us to do the other work we do, not just in promoting scholarship but also in seeking to educate world leaders and the public about the ongoing threat of genocide.