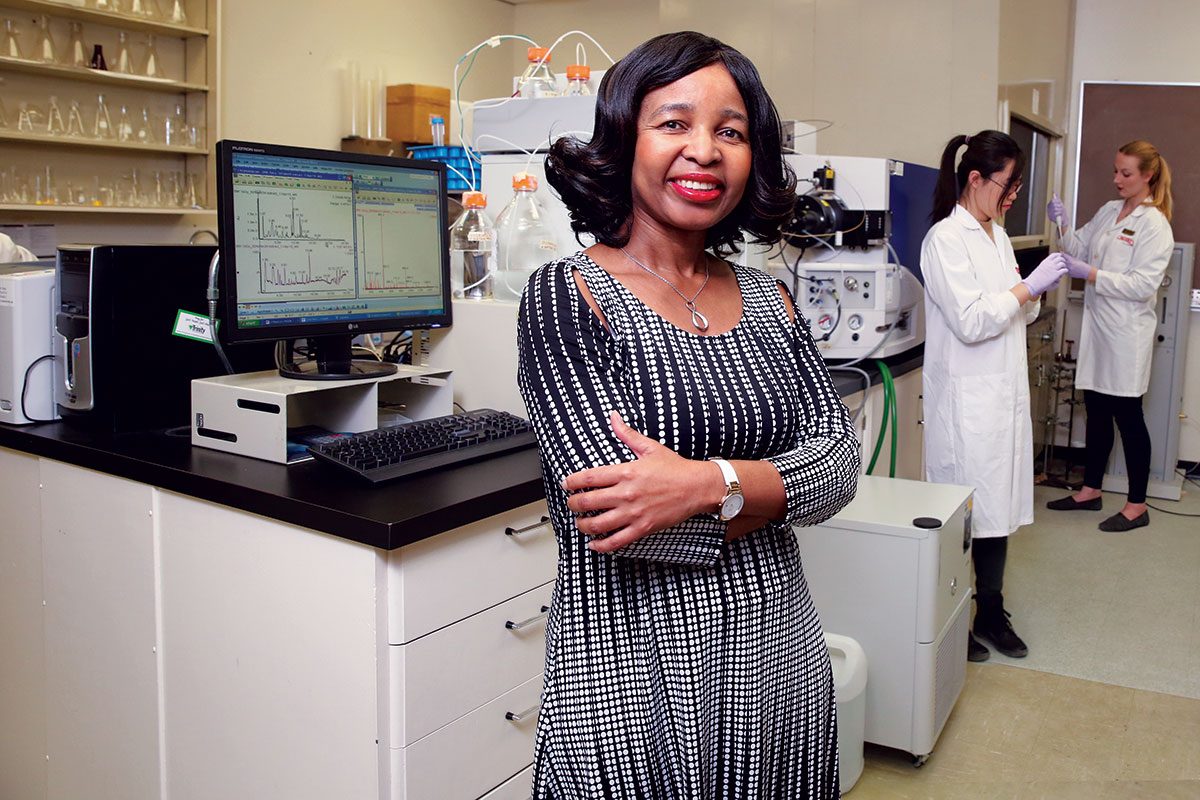

(L-R): Professor Trust Beta in her lab with students Yuwei Song and Pamela Drawbridge.

Cereal healer

In the past 10,000 years, the human population has grown from less than 10 million to more than seven billion today.

Most of the calories that made that boom possible have come from three grains: maize, rice and wheat. Their familiarity leads many to overlook them for fad food that seems innovative. But peel grains apart, and you discover they’ve been hiding a bounty of riches.

She knew the drink her mother made from maize on her family’s small farm in Zimbabwe was nutritious, but as a little girl, Trust Beta preferred the sweetness of Coca-Cola to the murky goodness of her mother’s brew.

Her mother, undeterred, kept leading the family towards wholesome foods, and Beta experienced a revelation of sorts when her mom had the family dry corn under the sun, boil it, then mix it with legumes to eat.

“We ate them whole, not ground,” Beta recalls. “And you can almost trust that there must be some health benefits in eating something in its wholeness, not fragmented with parts thrown out.”

“Look at the wholesome seed of wheat, how it is packaged. In your wisdom, you think you can make it more attractive by discarding parts, but what have you missed by doing that? Many, many, many things.”

As a former Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Food Processing for Grain-Based Functional Food funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Beta has investigated what components of whole grains can play a role in reducing obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer.

Her research program has evolved from fundamental exploration of plant biochemistry to discovering abundant stores of health-promoting compounds in Manitoba’s wild rice. Indeed, she has found over 30 such phytochemicals—non-nutrient chemicals, like antioxidants, made by a plant—in wild rice, wheat, barley, corn and rice. Now, companies such as Kellogg and Heinz seek her expertise to make their offerings healthier.

Beta’s research accelerated in 2008 when she received a mass spectrometer, an unusual piece of equipment for a food scientist. It allows her to investigate food like a chemist would—determining what molecules are locked inside the grain’s packaging.

Her resulting work built a database we have lacked since our ancestors began growing cereals 11,000 years ago.

“Getting this equipment was a highlight of my career because it was a game-changer,” she says.

“We made a breakthrough with wild rice. That was the first time we actually saw the various phytochemicals in wild rice, using that machine. Honestly, it’s like a dream come true in terms of just getting to know the details of any type of grain that you have been eating and taking for granted. Just to see how the phytochemicals were packaged. It’s a beautiful thing.”

PhD student, Pamela Drawbridge weighing a wheat flour sample as an initial step to determine the phytochemical in this particular variety of wheat.

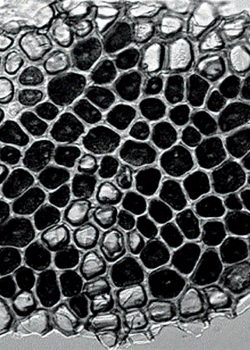

A cereal grain’s kernel has three prominent parts: the bran, or hard outer layer; the germ, a nutrient rich embryo that can grow into a new plant; and the endosperm, a large store of starch that bakers know as flour. But nature is always more wondrously complex than it first appears. A few years ago, Victoria Ndolo, a PhD student from Malawi working in Beta’s lab, undertook the excruciatingly cumbersome process of dissecting a grain of corn and barley—manually cutting the kernels’ bran under a microscope, without crushing it, into remarkably thin segments.

The frustration was worth it. She saw something no one else had seen: the bran had perfectly defined layers within it, and the layers held different human-health-promoting chemicals. Prior to this, science knew there were layers, but imagined them as blurry, intermingling boundaries.

“It took new technology and the patience of a woman to discover this,” Beta says with a laugh, which she does easily and often. Ndolo saw that an area called the aleurone is not, in fact, part of the endosperm. It is its own entity and it is rich—most of the health-boosting chemicals we want are tucked in this small space. This dietary treasure, hiding for thousands of years, was finally found.

Digital image of stained wheat aleurone residue with empty and filled cells.

Beta’s lab created the map, and now functional food companies are following it to exploit the bounty of this molecular hinterland.

“We always think we are the most sophisticated, higher organism, but within the grain, if you look at the detailed structure, you can appreciate that they are just as sophisticated as we are in a way,” Beta says.

Near the end of her PhD, Ndolo spoke at a symposium on functional foods. She was nervous because there were many medical doctors attending, speaking about flashy animal studies and the intriguing effects of chemicals on livers. Ndolo felt timid. All I have are these measly grains, she thought.

“I said, ‘You have to stop that mentality’,” Beta recalls. “Because those same grains, if they were being treated with respect, not just thrown away, no one would be unhealthy because they have the nutrition that we need. So I told her, ‘You are going to stand tall and show how sophisticated that grain is and why some people will be out of business—because if we can convince everyone to eat their whole grains, then we don’t need much of our medical facilities.’”

TRUST BETA IS REGARDED AS ONE OF THE WORLD’S FOREMOST CEREAL SCIENTISTS.

- She has published over 100 peer-reviewed papers and they have garnered over 2,000 citations, making her one of the most influential scientists in the field. Indeed, using an internationally recognized research metric tool, her papers are cited five times more than the world average in three different fields – Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Chemistry, and Medicine.

- She has a book currently in production by the UK’s Royal Society of Chemistry that she has co-edited on Cereal Grain-based Functional Foods.

- She has enhanced our understanding of how a plant’s genes and environmental conditions impact how many health-promoting compounds cereal grains can contain.

- She has contributed to improving grain-breeding programs, with the goal of producing grains of more uniform phytochemical [non-nutrient chemicals, like antioxidants, made by a plant] content and functional properties.

- Training and mentoring is integral in Beta’s program. In the past five years, she directly supervised 47 national and international highly-qualified students, including: eight postdoctoral fellows, 25 graduate and 14 undergraduate students from Canada, Brazil, China, France, Italy, Mexico, Peru and South Africa. To date, 12 of her trainees have become independent academic scientists and 28 are professionals within government agencies and leading food companies.

Story originally published in ResearchLIFE Summer 2018 Edition. Read the full magazine online.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.