Black River Primary School students perform at Zong memorial on May 9, 2017. Six school children performed a powerful, original chant – a poem entitled simply “The Zong” // Photo: Javier Uribe

An English professor’s journey through Jamaica: Or, how to keep history alive, mon!

The following is an account of a recent scholarly trip to Jamaica by English, Film and Theatre associate professor Michelle Faubert, a Visiting Fellow, Northumbria University. The trip came to be after a series of coincidences, beginning in the British Library and involving UM Today.

As an Associate Professor of Romantic-Era Literature here at the University of Manitoba, I never expected to make a significant historical discovery that would lead the Political Ombudsman of Jamaica, the Honourable Mrs. Donna Parchment Brown, and the Executive Director of the Institute of Jamaica, Mr. Vivian Crawford, to invite me to present to hundreds of people at multiple major events in Jamaica. Yet, these things happened. Now that I have returned from my exciting research trip to Jamaica (May 5-12), I reflect on my experience there as one of the most satisfying work experiences of my life, and I’ve learned several lessons that have changed who I am as a scholar.

The accidental start of it all

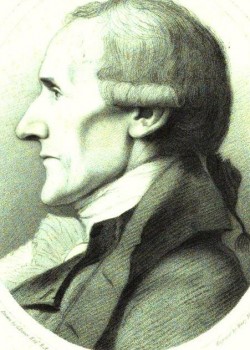

During my research at the British Library (BL) in May of 2015, I discovered a previously unknown manuscript, fair-copy of a letter from 1783 by Granville Sharp, the great British abolitionist, to the “Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.” The letter is about the infamous Zong slave-ship massacre of 1781, in which 132 slaves were thrown overboard to their deaths on the way to Black River, Jamaica. Sharp wrote the letter to demand that the Admiralty bring murder charges against the crew of the Zong.

My subsequent research has uncovered that this letter is the only fair-copy of Sharp’s letter to the Admiralty and that the only other known copy (at the National Maritime Museum) is a draft. The experts at the BL have confirmed that they did not know that this letter existed in their collections until I apprised them of its presence there. This discovery is significant: Sharp is widely known as the father of abolition and the Zong massacre has been called the “case that ended slavery.” Even though the crew was never tried for the murders, Sharp publicized the incident to the extent that, by the end of the 1780s, the horrible story of the Zong had helped to spark the abolition movement.

Finding this important letter turned me into something of an historian on the Zong; I became almost obsessed with discovering more about the case and the provenance (archival history) of the letter. I asked myself, Who owned this letter, and how did such an important document end up buried in the BL? I have published an article on this discovery in the pre-eminent journal on this topic, Slavery & Abolition (available here) and my book on it is now under consideration with publishers.

UM Today, it’ll make you famous

These publications were not the means through which my illustrious contacts in Jamaica learned of my discovery and research on the Zong massacre, though. An article that appeared in UM Today was their source of information. One Mrs. Evelyn Smart regularly received UM Today because she had hosted a University of Manitoba Master’s student in her home in Kingston, Jamaica, for a month.

Upon seeing the article on my discovery in UM Today, Mrs. Smart brought it to Mrs. Parchment Brown, whom Mrs. Smart knew was preparing a talk on the Zong to be presented at the Institute of Jamaica on December 22, 2016. Mrs. Parchment Brown included a reference to my discovery in that talk and later reached out to me about presenting on the topic in Jamaica. Excited, I replied the same day with my acceptance of her invitation.

I lectured on three occasions in Jamaica. The first was on May 9th: I was the main presenter at the Black River Zong Memorial event, where we announced the repair of the Zong monument, for which I helped to raise money by appealing to Scotiabank – yes, the Canadian bank! – one branch of which is located just up the road from the Zong memorial. Besides representatives from Scotiabank, in attendance were the Mayor of Black River, the Fire Chief, Representative of the Opposition party and students from the Black River Primary School. Six school children performed a powerful, original chant – a poem entitled simply “The Zong,” which was written by Miss Roschelle Sheriff and Mrs. Crisana Banton-Smith.

This was a moving event, as it took place in the very spot where the Zong slave ship landed. I felt humbled and honoured to speak on the Zong massacre at the very place where the survivors stepped onto Jamaican soil for the first time; perhaps, I considered, I was speaking to the survivors’ descendants. I opened my speech with some pertinent lines from the great Jamaican reggae singer, Bob Marley:

Stolen from Africa

Brought to America

Fighting an arrival

Fighting for survival

Driven from the mainland,

to the heart of the Caribbean.

A dozen people recited the lines with me. We later ate lunch in the same building where the slaves used to be washed and oiled to prepare them for sale at the nearby slave market. Beside the river – after we chased away the crocodile that was guarding the spot! – award-winning Jamaican journalist, Earl Moxam, interviewed me on the conditions of the Middle Passage between Africa and the Caribbean, my letter, and how Jamaicans might use this history to advance their efforts to gain financial reparations for slavery from Britain.

Scenes from that day are captured in many photos, such as the huge group photos of us near the repaired Zong memorial. When I look at them now, I wonder, why are we smiling so broadly? Is it inappropriate for us to feel joy at this sacred spot, where so many traumatized African slaves alighted from the floating hell that was the Zong? Yet, I recognize that those photos tell an important story about Jamaicans: they are determined to remember their history – to recognize it and honour it – but they refuse to be destroyed by it.

Scholarly work

“The Lost Letter and the Zong Massacre: Murder, Protest and . . . Suicide? An exhibition of a newly discovered manuscript letter by Granville Sharp to the Admiralty on the Zong murders (1783).” THIS EXHIBITION IS A 19-PART DISPLAY MADE POSSIBLE WITH SUPPORT OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES RESEARCH COUNCIL OF CANADA, THE INSTITUTE OF JAMAICA, AND THE POLITICAL OMBUDSMAN OF JAMAICA. // Photo: Javier Uribe

On May 10th, I presented a lecture at the University of West Indies, Mona Campus, Kingston, to an audience of around thirty scholars, librarians, and media, who were incredibly engaged and wonderfully challenging. The talk and discussion were supposed to be from 5:30 to 7 PM, and my talk was only about 20 minutes or so, as planned, but the formal question period and casual discussion went on so long afterwards that the event only ended at around 8 PM. I was exhausted, but delighted, by the time I arrived back at my hotel for supper afterwards.

Finally, after two morning interviews on national television to discuss my archival discovery and advertise the largest event – the “Zong Massacre Lecture Part II” on May 11th at the Institute of Jamaica in Kingston – the big day had arrived. Roughly 300 people were in attendance, including the Canadian High Commissioner to Jamaica and other governmental dignitaries, academics, lawyers, media, and students. The event opened with the Junior Centre Drummers, who wore the colours of the Jamaican flag and beat the bongos to call the immense crowd to attention.

Then a “Town Crier” regaled us with a reminder of our duty to remember the victims of Zong and celebrate the enduring spirit of the people of St. Elizabeth province, where the Zong landed at Black River. Several speeches followed, including my keynote address, but perhaps the stars of the show were the Black River Primary School children, who performed “The Zong” poem again for us. I also had the great honour and pleasure of meeting Mrs. Evelyn Smart, who had brought the UM Today article to Mrs. Parchment Brown’s notice.

Mrs. Smart gave me two of her books on women in Jamaican politics, a topic dear to my feminist heart. At the same event, we launched the exhibition I created for the Institute of Jamaica, entitled, “The Lost Letter and the Zong Massacre: Murder, Protest and . . . Suicide? An exhibition of a newly discovered manuscript letter by Granville Sharp to the Admiralty on the Zong murders (1783).” This exhibition is a 19-part display that includes colour scans of the letter I discovered at the British Library and my transcription and examination of its key passages; two title posters; and a biography/research poster. The exhibition will travel to Black River in October for Jamaican Heritage Month.

Scholarly lessons

Michelle Faubert (left) connecting with the wider public on CVM Sunrise TV, Jamaica. // Photo: Javier Uribe

Through my incredible experience in Jamaica, I learned many things, and a few of them have changed who I am as a scholar. To begin with, I realize now how very true it is that we scholars must connect with the wider public and make our research live for everyone, rather than focussing solely on a scholarly audience.

This is an injunction that the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) reiterates often; since I made my discovery of the Sharp letter at the British Library and funded the trip to Jamaica through my SSHRC Insight Grant (2015-20), I was eager to put this theory into practice – and I was rewarded thoroughly for my efforts. I presented to hundreds of Jamaicans (and perhaps thousands of television viewers of the morning interviews!) about my research and was met with excitement, curiosity, and intellectual engagement like I have seldom experienced.

I also learned that we scholars must take every possible opportunity to disseminate our research, since one never knows the avenues through which something great will happen. Who could have guessed that the article on my discovery in UM Today would be seen by a woman in Jamaica? Moreover, how many Jamaicans would have known that Mrs. Parchment Brown was preparing a presentation on the Zong and would have taken the time to bring the story to her?

Such serendipity appears especially amazing when I consider what else I learned in Jamaica: that many adults in this well-educated nation have not heard of the Zong massacre. Their knowledge of their history, including that of slavery, is thorough, but somehow mention of the “case that ended slavery,” as the Zong case is often dubbed, has been left out of the narrative – even though the slave ship landed in Jamaica, and the survivors’ descendants may well live in Jamaican society to this day.

In a recent message, Mr. Vivian Crawford of the Institute of Jamaica thanked me for “creating such excitement for good in Jamaica”; I think he meant the good of helping him and Mrs. Parchment Brown to keep Jamaican history alive by telling the story of the Zong massacre. I feel that they and so many other Jamaicans I met during the course of my visit have done me a great good, too: they have reinvigorated my excitement for my research and my efforts to disseminate it widely, and they have shown me that, no matter how old my topic may be, it may still be made relevant to people today.

What a wonderful article !

The end result of significant research (and a little luck perhaps) was opening up a much broader story to unfold, especially for the Jamaican people.

Well done Ms. Faubert