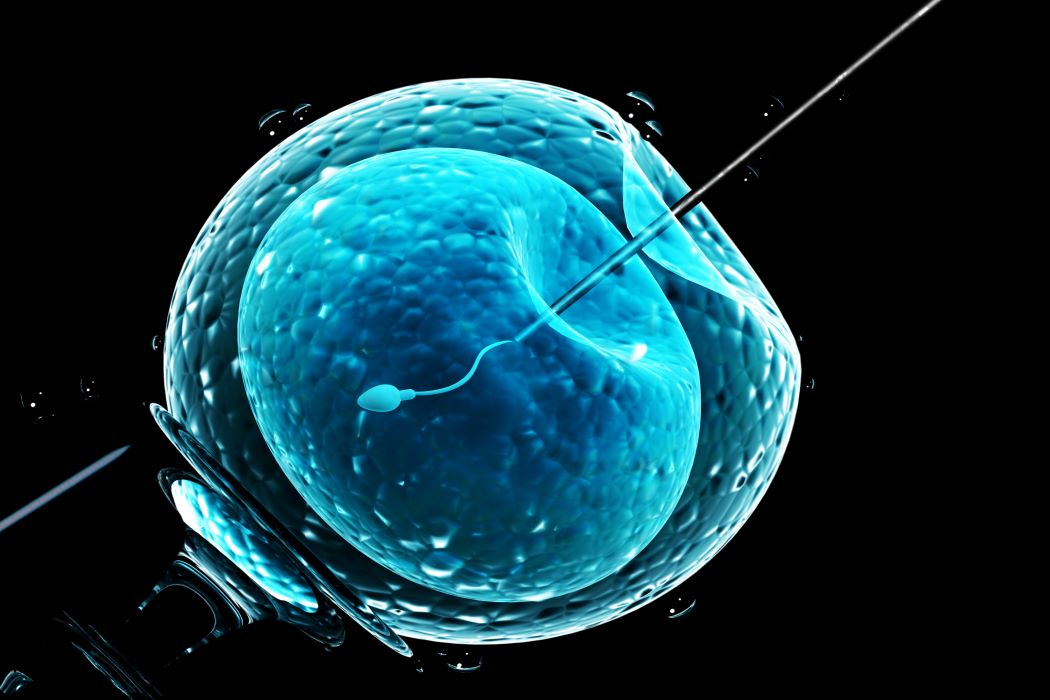

UM scientists to investigate why embryos fail to implant after in vitro fertilization

Study receives prestigious U.S. funding

It’s a heartbreaking statistic for would-be parents: Up to 40 per cent of genetically normal embryos that are transplanted into a uterus following in vitro fertilization (IVF) don’t successfully implant and result in a healthy pregnancy.

A team of UM researchers believes the key to this fertility mystery could lie in the microbiome – the invisible microorganisms, such as bacteria, living in the mother’s or father’s urogenital tract – or possibly in the combination of the two partners’ microbiomes.

If this is found to be true, the scientists say, it could one day lead to some couples’ infertility being resolved with inexpensive antibiotics or anti-inflammatory drugs.

DR. ALICIA BERARD

“Starting in the new year, we’re going to recruit heterosexual couples who are undergoing IVF in Winnipeg so we can investigate factors underlying fertility and IVF success in a more in-depth way than anyone has before,” says Dr. Alicia Berard, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences in the Max Rady College of Medicine.

Berard and her UM co-investigators, along with research partners at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, have received a prestigious five-year grant of nearly US$2.9 million for the study. The funder is the National Institutes of Health, the national medical research agency in the United States.

More than US$860,000 of that funding will come directly to UM.

The team will recruit 100 research-participant couples at Heartland Fertility, a Winnipeg clinic. Dr. Jason Elliott, assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences and researcher with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba (CHRIM), will be the clinical site lead at Heartland.

Samples will be taken of the men’s semen and penile microenvironments and the women’s vaginal and uterine microenvironments.

Participants will also provide information on factors such as their diet, sex and hygiene behaviours, medication and substance use. Their embryo transplants that do succeed will be tracked for outcomes such as miscarriages, preterm births and birth weights.

Berard, a microbiologist who has studied the vaginal microbiome in conditions such as bacterial vaginosis and human papilloma virus infection, will lead the study lab at CHRIM.

The researchers will use state-of-the-art “systems biology” tools such as proteomics, transcriptomics, flow cytometry and single-cell RNA sequencing to analyze the samples in a novel, comprehensive way. Samples and data will be sent to Ohio for some types of analysis.

“We want to dive deep into the microbiome and look at the function of the bacteria, as well as the function of molecules like proteins and metabolites, and the role of immune cells,” Berard says.

“Studies have shown that a vaginal microenvironment dominated by Lactobacillus bacteria – not a diversity of bacteria – is beneficial because you have less inflammation, a lower chance of acquiring sexually transmitted infections, and lower chances for poor reproductive health outcomes, including preterm birth.”

A Lactobacillus-dominated vaginal microenvironment is also associated with successful embryo implantation, Berard says, but scientists don’t know why.

“Because the microbiome plays a role in inflammation, we think there may be inflammatory processes preventing some women from having a successful pregnancy.”

On the male side, the team aims to investigate whether microbiome factors are associated with differences in semen quality, such as the motility and concentration of sperm.

The study will be the first to look for intra-couple microbiome factors that may work together to promote success or failure in embryo implantation.

About one in eight couples worldwide experiences infertility, Berard says. “A lot of people feel like it’s a failure on their part, but it’s not. Sometimes it comes down to simple biology.

“If we understand more of the ‘why’ of infertility, we can understand how to mitigate it. IVF is very costly and is out of reach for many families, especially if IVF needs to be performed multiple times.

“If we can shed light on the microbiology of pregnancy in couples undergoing IVF, we hope it will lead to reduced numbers of IVF attempts. It may even identify treatments that could help people to have successful pregnancies naturally.”