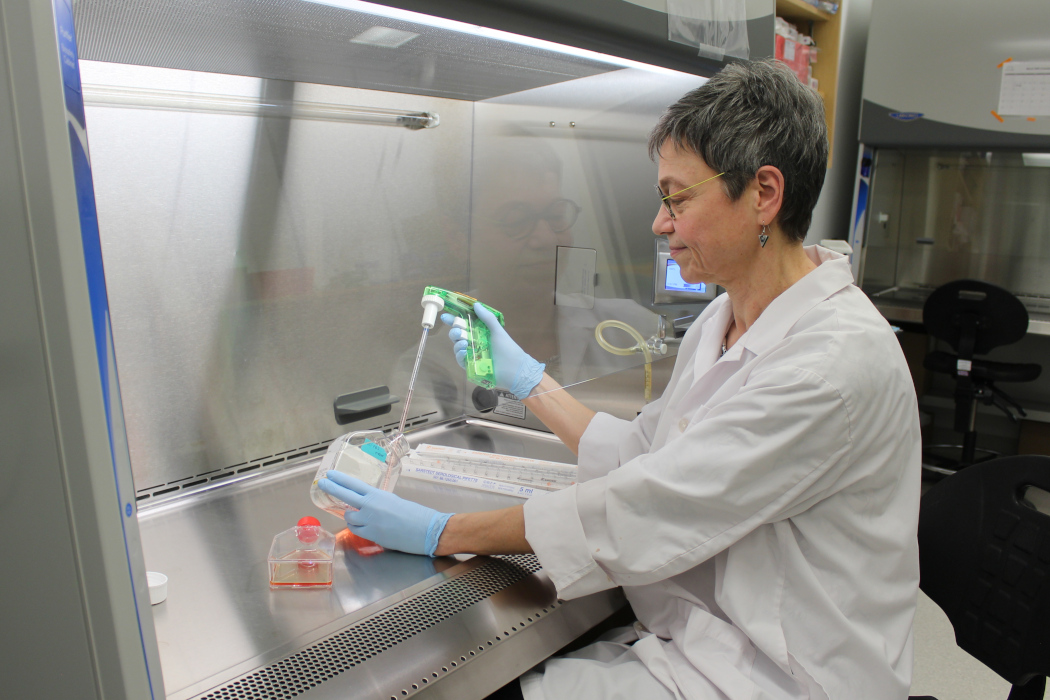

Dr. Sabine Hombach-Klonisch

UM-led study offers hope that existing drug can target metastatic brain tumours

A University of Manitoba-led study successfully eliminated breast-cancer derived brain tumours in mice, using a drug to penetrate the brain and eliminate metastatic brain tumours.

After testing 8,500 drugs, the research team discovered that poziotinib – a drug that already exists and is approved for other cancers – reduced breast cancer brain metastasis tumours in mice after two weeks of treatment.

Brain metastasis occurs when cancer cells spread from one part of the body to the brain and form tumours. This study focused on HER2-positive breast cancer, which contains abundant levels of HER2 protein that promotes the growth of cancer cells.

[Left to right] Dr. Danyyl Ippolitov, Dr. Sabine Hombach-Klonisch and Dr. Thomas Klonisch.

Brain metastasis can happen years after successfully treating a breast cancer tumour and occurs in about 50 per cent of individuals with HER2-positive breast cancer, says Dr. Sabine Hombach-Klonisch, professor and head of the department of human anatomy and cell science at the Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

“This is a huge success,” says Hombach-Klonisch, a lead author of the study that was recently published in the journal Cancer Research.

“We set out to look for drugs that would penetrate the brain, and also effectively reduce the metastatic brain tumour and we found a drug that did that. It’s a leap forward in reducing the tumour mass in the brain.”

The scientists were faced with finding a drug that could penetrate the blood-brain barrier, a layer of cells that acts as a filter and protects the brain. Hombach-Klonisch says that many cancer drugs that work in other parts of the body can’t enter the brain in high enough concentrations to be effective, and brain cells surrounding the tumour produce growth factors that can cancel the success of many drugs.

“The brain penetrability of current drugs is low,” Hombach-Klonisch says. “We have shown that poziotinib actually has a high concentration in the brain after administration. Drug levels remain long enough to have a therapeutic concentration before they drop.”

Study co-authors from the Max Rady College of Medicine include first author Dr. Danyyl Ippolitov, research associate in the department of human anatomy and cell science, Dr. Jason Beiko, assistant professor of surgery, Dr. Marc Del Bigio, professor of pathology, and Dr. Thomas Klonisch, professor of human anatomy and cell science.

“This research is important because many patients with breast cancer are waiting with uncertainty, not knowing if brain metastases will occur and whether there will be a drug that’s effective in treating it, so I think it gives them hope,” Hombach-Klonisch says.

Hombach-Klonisch anticipates the drug and its use in treating brain tumours will soon be tested in clinical trials.

She says the research project will continue because they have plenty of questions to answer, such as how many tumour cells are left after treatment with poziotinib and what needs to be done to prevent recurrent tumour growth?

The study was funded by the Cancer Research Society in partnership with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and CancerCare Manitoba. Studentship funding was received from CIHR.