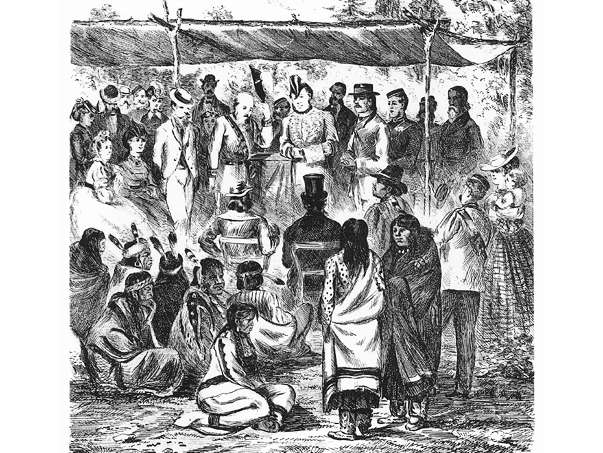

Conference with First Nations Chiefs during Manitoba-First Nations Treaty, 1871. // Glenbow Archives NA-1406-72

The role of Indigenous women in Treaties and traditional governance

As part of Indigenous Awareness Week, which takes place March 16 to 21, panelists will come together to discuss the role of Indigenous women in Treaties and traditional governance. Panelists for the session, which takes place Tuesday, Mar. 17, are: Aimée Craft, Faculty of Law; Kiera Ladner, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Politics and Governance; Janice Bone, U of M graduate student, department of Native studies; and Margaret Lavallee, Elder-in-residence at the U of M.

UM Today spoke with panelist Aimée Craft, an Indigenous lawyer in Manitoba and assistant professor in Faculty of Law.

Two systems of law confronting each other

In addition to working in Treaty and Aboriginal rights for over a decade, Craft says she’s tries to understand the role of Anishinabe tradition in daily life.

“We often don’t talk about Indigenous philosophy; we talk about a way of life,” she explains. “That’s very important for me in my personal life and also translates into some of my academic work.”

Her recent book, Breathing Life Into the Stone Fort Treaty – an Anishinabe Understanding of Treaty One focuses on understanding and interpreting Treaty in terms of underlying principles of the Anishinaabe inaakonigewin (legal) perspective.

As she notes, the foundation for the understanding of Treaty 1 was based in the law of the land at the time and “Anishinabe law was alive and well” in 1871.

Breathing Life Into the Stone Fort Treaty – an Anishinabe Understanding of Treaty One by Aimée Craft.

In her work, Craft looks at the Anishinabe understanding of “Mother Earth — and Earth as a Mother.” It leads, she says, “to the understanding of the ability we have to share in the bounty of Earth, but not make decisions for the Earth and not to sell the Earth — but to live in relationship with it.”

The mother-child relationship is also the basis for Treaty with the Queen. Craft points out that through the Treaty process, both English commissioners and the Anishinabe spoke about the relationship with the Queen as a mother.

However, understanding diverged in “those underlying legal and normative value systems,” she says.

“When the commissioners with their English law background are coming to the table and talking about the Queen as a mother, they are thinking in terms of child labour in England, hierarchy amongst children from oldest to youngest, differences between male and female children, children not having any legal identity.”

This is contrasted with an Anishinabe understanding of the mother-child relationship, founded on “love, kindness and caring and fostering of autonomy,” shes says.

“You are a person from the moment you are born — even prior to being born — you exist as a person in Anishinabe law, and you have that ability to make your own decisions and to have your autonomy fostered by both parents.”

Though there’s no disagreement about the terminology used in the Treaty, she points out, “it results in a substantive misunderstanding, that is different on both sides.”

“It’s two systems of law, really, that are confronting each other,” she says.

Reclaiming the role of women

So often, says Craft, “we either blend roles of male and female in our understanding of governance and Treaties — or we absent the role of women.”

There are important principles — and historical precedent — for the integral role of women in governance, she says.

For example, “the Anishinaabe work in a clan system and structure highly influenced by clan grandmothers — and women have strong roles in terms of leading the direction of decision making and action in our communities.”

These traditions and underlying principles have been been overshadowed. “It’s an important awareness piece in exploring historically what women’s roles were in governing our nations and family units,” she explains. Craft is interested in exploring how that governance role — both on a micro and macro level — can be reclaimed and better understood today.

Treaties, governance and Indigenous women

The integral role of women is not always reflected in modern politics, she notes.

Says Craft, “The Treaties are a marking point in time, where it’s necessary on the commissioners’ part to deal with male counterparts and maybe not a recognition of the underlying system of governance that incorporates the governance of women and the jurisdiction of women over water and land.”

It’s key in the Western misunderstanding of Treaty, she notes.

“First of all, that the ability to make decisions belongs to the collectivity and not the individual and the refusal of the commissioners to deal with the whole body of people, but rather the selection of certain individuals to represent — it somewhat defies the governance structures at the time. And it certainly is the beginning of patriarchy in structure and governance.”

Patriarchy was further reinforced through the Indian Act, says Craft, with registration provisions based on discrimination between male and female members, as well as band election structures that didn’t allow for women to be elected.

Craft calls it “a procedural beginning of the imposition of patriarchy.”

Some of it was effected through the fur trade as well, she explains. And though the spokesmen were male, it’s important to remember that Indigenous camps “were run by women. And there where over a 1,000 people at the Treaty 1 negotiations. And they were going back into discussion with family and community clans and trying to understand and collectively make those decisions in camp.”’

She clarifies that the governance structure was taking place, “but maybe not as visibly in the eyes of the commissioners and those who are reporting on the historical record.”

“It’s not by accident that everyone comes together to the Treaty negotiations. It’s not just a group of men who arrive together to negotiate. It’s everyone that is there.”

***

Craft’s desire is that the panel will achieve further learning about the role of Indigenous women in governance both within the university, and within Indigenous communities. She sees a need for some of these difficult questions to be faced head on, citing the current lack of Indigenous women in leadership — only four of 56 Indigenous Chiefs in Manitoba are women, as she points out.

“My hope is that there will be a lot of people that attend the entire [Indigenous Awareness Week], and that we won’t have this panel and have only women show up. I think that there needs to be a balance of Indigenous and non-Indigenous men and women that come to hear and participate in the discussion.”

The session, “The Role of Indigenous Women in Treaties and Traditional Governance” takes place in 543-544 University Centre on Tuesday, March 17 from noon until 2 p.m.

–Mariianne Mays Wiebe

>> See story on Indigenous Awareness Week here and more on individual panels here.

***

The Role of Indigenous Women in Treaties and Traditional Governance

Indigenous women played a central role in determining the contents of the Treaties. What was this role? And how has it been interpreted over history? We’ll look at how Indigenous women are looking to the past and re-imagining themselves in governance roles today and in the future.

Location: 543-544 University Centre

Date and time: Tuesday, March 17, noon to 2 p.m.

Panelists

Aimée Craft, assistant professor, Faculty of Law

Kiera Ladner, Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Politics and Governance

Janice Bone, U of M graduate student, department of Native studies

Margaret Lavallee, Elder-in-residence, U of M

What is the origin of the mother & child photo? I was told it was a picture of a relative of mine who’s name is Marguerite Sarcee. I’m trying to find the origin & accuracy of that statement.