Sewing the beads of change

Sherry Farrell Racette’s current project, “The Sewing Circle,” draws on the history of the women of Batoche.

Death War and Sacred Spaces, handmade book with beadwork and leather cover by Don Hall, courtesy of the MacKenzie Art Gallery

“I believe in the power of beadwork; the power of the stitch to create change and facilitate healing,” as she puts it.

With a background in art history, education, history, anthropology and Native studies, the member of Timiskaming First Nation in Quebec has taught at universities in Regina and Montreal. At the U of M, she is an associate professor crossappointed to the departments of Native studies and women’s and gender studies. Her multifaceted art practice often draws on her archival research.

Farrell Racette has also been involved in several projects that pair beading with community action. Two are “Common Circles: Art and Community Violence,” a community project in Regina, and “Walking With Our Sisters,” a collaborative installation (initiated by Métis visual artist and author Christi Belcourt) of 1,800 pairs of beaded moccasin tops — called vamps — that honours missing and murdered Indigenous women. Besides leading two beading circles for “Walking With Our Sisters,” she sits on the national committee and is working on the project catalogue.

It’s apropos, then, that her current project will bring to life “The Sewing Circle,” a poem from Métis prize-winning poet Gregory Scofield’s 2011 collection, Louis: The Heretic Poems. Besides a shared passion for beading and revivifying history, she and Scofield are good friends, says Farrell Racette. “We often talk about our shared history and we are both passionate beaders, although he is much more accomplished than I am. We taught beadwork together at the annual Back to Batoche celebration a few years back, and I wrote an essay for his instructional book Wapikwaniy: a Beginner’s Guide to Metis Floral Beadwork.”

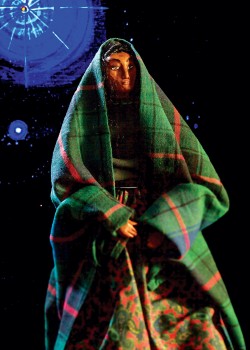

A woman walks through the darkness on the eve of the final battle of Batoche, Saskatchewan Resistance 1885. Test shot of handmade puppet prototype for The Sewing Circle, a short film based on a poem by Gregory Scofield. // Photo by Eagleclaw Thorn.

The artist will transform the poem into a short film featuring music by her daughter, a musician, and her own handmade puppets that will represent the women and wives who were involved in the Saskatchewan Resistance. Set in 1885 during the last stand led by Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont, the poem imagines the conversation of the women, including Marguerite Monet Riel and Madeleine Wilkie Dumont, gathered together the night before the fall of Batoche.

The foray into film was inspired by Farrell Racette’s immersion in Native women’s filmmaking thanks to “Native Women and Film,” an annual festival she’s co-curated over the past five years as part of the women’s and gender studies program. Hearing Scofield read his poem aloud was another impetus.

“As he read [the poem],” she says, “I could see it unfolding. I know the history, but the poem adds a dimension to what we know — or what we think we know because so much of the story has been retold and documented from a male point of view.

The three-day Battle of Batoche marks a historical turning point for Métis people, and particularly for those in Saskatchewan, notes Farrell Racette. The reading resonated partly because she had already done substantial research on the women and families of Batoche.

“I grew up hearing stories of Louis Riel from family friends and neighbours in Manitoba. Later, I worked in a teacher-training program for the Gabriel Dumont Institute (GDI) and heard the stories from Saskatchewan,” she says. The late Shannon Twofeathers, who worked for GDI collecting stories from elders at Batoche, passed on many stories.

The stories were her catalysts, she says. “One story in particular — of women hiding in the caves at Batoche while war raged around them and their homes were burned by the Canadian military — had a profound impact on me, and I went home and painted it.”

Story Blanket: Kooshkopayiw/Awaken/Eveiller for Métis Rights Niche, 2 of 2 panels. // Photo by Sherry Farrell Racette

Painting the scene spurred several additional artworks and a good deal of academic research on women, and resulted in an exhibition she curated at the Parks Canada Heritage site, entitled “Resistance/Resilience: Metis Art: 1870-2011.”

“You’re actually manipulating in a very real way the facts of history; you’re literally sewing them, or you’re painting them, or you’re carving them. There’s something about that process that I find really compelling.”

A commissioned installation she did for the Canadian Museum for Human Rights includes the story of Batoche from a woman’s point of view.

“The stuff that I found out over time that happened to the women at Batoche is really not widely known,” she says. “It’s a way to feminize history — because that is part of my wider project, to bring forward women’s stories.

In addition to the archival materials she gathered, meeting with the descendants of families who stayed and rebuilt Batoche has been a significant aspect of her research, an approach that is typical for her. Her way of working is motivated by the sense of responsibility she feels to the communities whose stories she tells.

Nagamotaw Kateri (Singing for Kateri) egg tempera, gold leaf on deer hide parchment. // Photo by Sherry Farrell Racette

She explains, “I talk to people; that’s my way of doing oral history research, sort of hanging around, talking to people. When I was doing research about the fall of Batoche, I was finding photos of the women and the people involved — and those will become tiny details [in the video] and it has to be right.”

Farrell Racette is compelled by the tangible and symbolic power of this creative work and research, a power that draws on community connection. “That’s the difference,” she says, “I sort of don’t have creative license. I am acting on behalf of someone … I’m doing this for people. I’ll go back and I’ll say, have I got it right?

“Something about the physical manipulation as part of the creative process for me takes my thinking and my analysis deeper,” she adds. “Because you’re actually manipulating in a very real way the facts of history; you’re literally sewing them, or you’re painting them, or you’re carving them.

“There’s something about that process that I find really compelling.”

This story was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Research Life.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.