L-R: Stan Saunders (Youth Advocate, Zoongizi Ode), Chelsea Bannatyne (Research Assistant), Dr. Christine Mayor (Faculty of Social Work, University of Manitoba), Dr. Julie Chamberlain (Inner City and Urban Studies, University of Winnipeg), Michael Redhead Champagne (Co-Founder, Zoongizi Ode), Mary Burton (Executive Director, Zoongizi Ode), Sharon Janakas (Research Advocate, Zoongizi Ode), Seka Lussier (Community Engagement Specialist, Persons Community Solutions). Not pictured: Madrin Macgillivray (Research Assistant), Farjana Yeasmin (Knowledge Mobilization Assistant), Daniel Waycik (Co-Founder, Persons Community Solutions) //PHOTO BY: FARJANA YEASMIN

Rebuilding safety with care in public spaces: New research reports how Winnipeg’s Community Safety Hosts practice wâhkôhtowin

In Winnipeg’s public spaces like libraries, hospitals, shelters, and government service buildings, safety has often meant exclusion: watching, pushing aside, or banning those already marginalized by poverty, mental health struggles, and discrimination. But what if safety was reimagined as belonging, where the measure is not how many people are removed, but how many feel they truly belong? That’s the question Winnipeg’s Community Safety Host Program – an Indigenous-led, people-centred alternative to security guards – is answering every day, guided by wâhkôhtowin. Research led by Dr. Christine Mayor, Inner City Social Work, University of Manitoba and Dr. Julie Chamberlain, Urban and Inner-City Studies, University of Winnipeg reports the ways in which Community Safety Hosts embody wâhkôhtowin through their everyday work in public spaces.

Measuring safety by belonging

Wâhkôhtowin, a Cree and Métis worldview, emphasizes that we live in a universe defined by relatedness, and that we have responsibilities to respect and care for one another.

Access to public spaces like libraries, healthcare, and government service buildings is essential for education, employment, and housing support. Yet many face racism and stigma around substance use, mental health, and poverty that block these access points. Staff often lack the capacity or training to support people in crisis. Traditional security can push vulnerable people away and sometimes escalates harm by involving police.

The Community Safety Host program was designed to address these challenges directly. It offers an Indigenous-led, people-centred alternative to security guards in shelters, libraries, and community centres across Winnipeg. Community Safety Hosts receive security training plus specialized training in compassionate, trauma-informed care, harm reduction, mental health, working to address root causes of oppression, and accepting people as they are—helping rather than rejecting. All of the training is rooted in wâhkôhtowin, training Community Safety Hosts to treat all they encounter as though they are kin.

Reframing crisis through connection

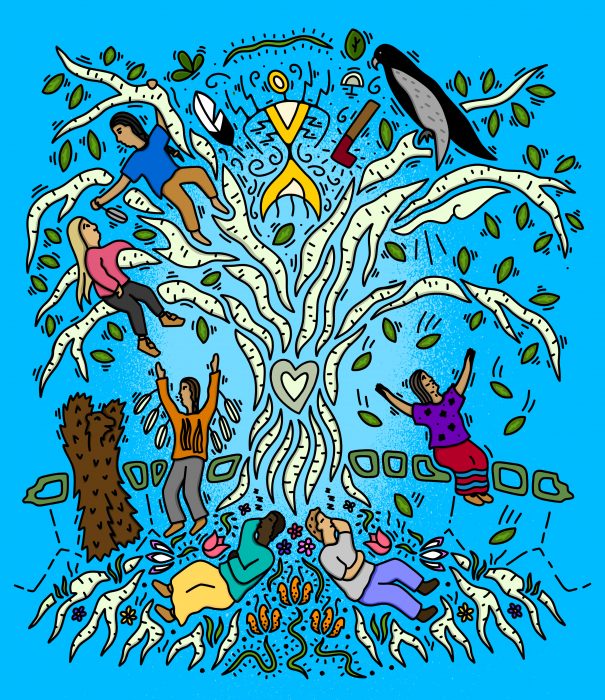

Anishinaabe artist Jordan Stranger represented the research findings in commissioned artwork called “Nitotem,” visually depicting the seven interconnected ways that Community Safety Hosts embody wâhkôhtowin through their work.

For more than a decade, Daniel Waycik worked in community safety programs and sensed something was missing. Policies focused on security but rarely addressed relationships or the deeper reasons behind crises. When he began working with Zoongizi Ode on the Housing Solutions Lab and later co-founded Persons Community Solutions (PCS), wâhkôhtowin gave him the grounding and language to transform his work.

“Wâhkôhtowin isn’t just another framework—it’s one of the most grounding value systems I’ve worked with because it gets something fundamental: everyone has gifts.”

Community Safety Hosts bring their authentic selves and lived experience to everyday moments: helping someone untangle government forms, sitting quietly with a grieving person in a library corner, or walking alongside someone to a shelter. Waycik cautions that no single program can fix poverty, housing shortages, or broken systems, but he has witnessed how Community Safety Hosts “soften the harshness” of these realities by treating people like they matter—creating small pockets of hope in places where many feel watched, judged, or pushed out.

As Waycik noted, “When I watch our Community Safety Hosts work, I see wâhkôhtowin lived out in ways that still surprise me. Incidents aren’t urgent—addressing people’s needs in a timely and trauma-informed way is. What frontline responders grounded in wâhkôhtowin all share is this ability to see past the crisis to the person and help that person see their own strengths and possibilities.”

A program shaped by lived experience

Community Safety Hosts didn’t emerge from a boardroom. Instead, the program grew from the voices of people who knew what it meant to be made unwelcome in public spaces. Through the Housing Solutions Lab, Zoongizi Ode gathered stories from community members who recounted being followed, questioned, or told to move along when they simply wanted a warm place to sit or access to a computer.

Mary Burton, Executive Director of Zoongizi Ode, describes how these conversations shaped the program:

“When we started the Housing Solutions Lab, we wanted to find out what our community and relatives needed. The concept was never heard of until we collaborated with PCS. Since 2021, we have worked tirelessly to make it safe for folks with lived experience to learn and grow and to share their experiences in a good way. I am super proud of everyone and everything we have created here with the Community Safety Hosts!”

The Community Safety Host program also provides meaningful employment opportunities for young people aging out of care and others with lived experience of poverty, homelessness, incarceration, and exclusion. Hosts draw on their own histories to recognize when someone is struggling, de-escalate tense situations, and connect people with food, housing, healthcare, and other supports.

Wâhkôhtowin: Researching the heart of community safety

Research conducted by Dr. Mayor and Dr. Chamberlain highlights a critical distinction between “security” and “safety”: “Security often focuses on securing buildings, property, and the privileged few. Prioritizing true community safety means rejecting security for a few and instead focusing on safety for all through community care, relationship building, and ensuring that everyone has access to what they need, which includes food, housing, healthcare, emotional support, clothing, and more. Our research demonstrates how the Community Safety Hosts’ practice of wâhkôhtowin is one way of creating community safety for all here in Winnipeg.”

At the core of the Community Safety Hosts’ approach is wâhkôhtowin, an understanding that we live in a universe defined by relatedness and responsibilities to care for one another.

The community report, “How Community Safety Hosts Practice Wâhkôhtowin and Create Safety through Relationship Building” (Mayor et al., 2025), outlines seven interconnected ways the hosts embody wâhkôhtowin through their work:

- Sharing kindness and concern

- Taking care of those needing protection and guidance

- Giving loving support without judgment

- Connecting people to a circle of relationships

- Holding people accountable within the community

- Helping people find their role and responsibility

- Giving gifts of time and willingness to listen

As their research demonstrates, true community safety isn’t about locking down buildings—it’s about securing relationships, reminding us we are kin, deeply interconnected.

Rethinking what safety means

Research by Dr. Mayor and Dr. Chamberlain highlights a powerful distinction: traditional security often prioritizes property and protection for the privileged, while true community safety focuses on people, especially those marginalized, through care, connection, and meeting essential needs.

Community Safety Hosts are living proof that safety can be reimagined and rebuilt with relationship-centred care at its foundation. Their work offers a model for cities seeking to move beyond enforcement toward community-led safety.

At the report launch in the Millennium Library’s Carol Shields Auditorium in October 2025, hosts, community partners, and researchers shared transformative stories: spaces once intimidating have become welcoming places where someone greets you by name, listens without judgment, and helps you find what you need. Anishinaabe artist Jordan Stranger represented the research findings in commissioned artwork called “Nitotem,” visually depicting the seven research themes.

Yet, a safe community in which everyone’s needs are met does not yet exist in Winnipeg.

True change in systems and policies is needed to ensure all people have what they need to thrive. The CSH model offers a strong foundation to develop similar initiatives in Winnipeg and beyond. If wâhkôhtowin is put into practice across different public spaces and relationships are centred at the heart of safety, change can happen in Winnipeg and beyond.

Wâhkôhtowin offers a vision of safety where everyone is seen, supported, and included, where community connections become the strongest form of protection.

To read the community research report, please visit: https://mra-mb.ca/publication/how-community-safety-hosts-practice-wahkohtowin

For more information on the research, please contact Dr. Christine Mayor at: christine.mayor@umanitoba.ca or Dr. Julie Chamberlain at: j.chamberlain@uwinnipeg.ca

For more information on Community Safety Hosts, please visit: https://pcs-scp.ca/