Spring surface runoff forming a swale over typically flat Prairie land. Photo Credit: Genevieve Ali.

Prairie Water Problems

Water is an important topic in Manitoba but to date it has been difficult to accurately predict how much water will occur in any one place at a given time. Historically, theoreticians in hydrology have mostly avoided dealing with flat regions such as the Prairies; when your first scientific principle is that water flows downhill, it is natural to discard mountain-free regions as simple exceptions to the rule. This then explains why most commercial hydrological models fail to provide accurate runoff predictions when applied to Manitoba, as they were designed to simulate water movement over sloping terrain. In the wake of water disasters such as the 2011 or 2014 Manitoba floods, public criticism was largely directed towards those responsible for predicting the onset of extreme river flows and managing emergency situations. Dr. Genevieve Ali (Junior Chair, Watershed Systems Research Program, Department of Geological Sciences and the Centre for Earth Observation Science (CEOS)) however argues that most of the uncertainty associated with flood prediction and management comes from a lack understanding of Prairie hydrology. Putting it simply, the trivial question that hydrologists face is “how do meltwater and rainwater move over Prairie landscapes?”The present – day answer is “we do not really know”. In the meantime, the commercial models that Prairie hydrologists rely on do a poor job simulating not only water infiltration into frozen soil but also river ice jamming that leads to early spring flooding, water storage in wetland depressions, and subsurface runoff.

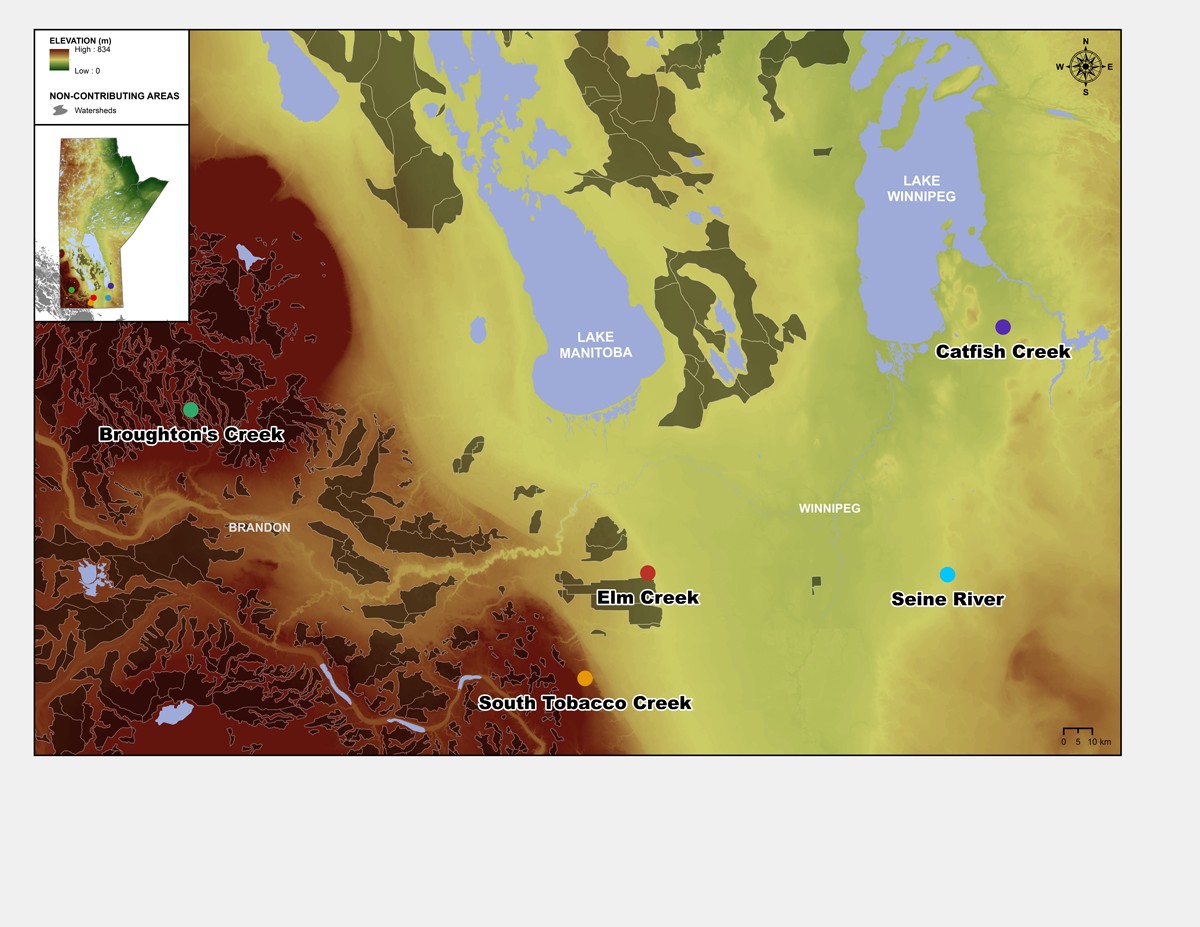

One of the most challenging Prairie water problem is related to the prediction of water movement velocities depending on whether the landscape is subject to surface runoff, subsurface runoff, or both. Another equally challenging problem has to do with the connection, or lack thereof, between above- and below-ground processes. This is especially true in human- impacted systems where surface drains, tile drains, and retention ponds can promote the leakage of surface water – and its associated pollutants – into deep groundwater aquifers. To tackle those surface-subsurface runoff interactions, Manitoba’s Watershed Systems Research Program (WSRP) has set up a network of hydrological observatories to deploy instrumentation in the Prairie Pothole Region, the steep Pembina escarpment, and the flatter Red River and Winnipeg River Valleys. For instance, research in Broughton’s Creek Watershed focuses on how surface and subsurface pathways facilitate the exchange of water and nutrients between rivers and seemingly isolated pothole wetlands. In the South Tobacco Creek Watershed, the aim is to understand how subsurface water flows through connected bedrock fractures before discharging into surface waterways, thereby increasing flood water volumes. As for sites in the Red and Winnipeg River valleys, they are used to compare the dynamics of subsurface runoff in clayey, sandy and peaty soils.

With such a variety of study sites, one goal of the WSRP is to identify which landscape characteristics are responsible for the spatial variability of surface and subsurface runoff, and subsequently revise the structure of runoff prediction models. Another goal is to figure out whether water and pollutants are flushed out of Prairie watersheds in a matter of hours, days, years, or decades. This information will be critical to inform managers on the delay between the time when nutrients responsible for eutrophication are applied on land, and the time when those nutrients are expected to emerge in Lake Winnipeg. This information, however, will only become available (and reliable) after solving the previously mentioned Prairie problems… one at a time.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.