Researchers have found that those who feel more connected to nature tend to feel more connected to all of humanity. (Annie K/Unsplash)

People who feel more connected to the natural world are more likely to support reconciliation

Many Canadians want to know what they can do to honour Indigenous children and further reconciliation, in light of the recent discovery of more than 1,000 unmarked graves at the sites of former Indian Residential Schools.

But what does “reconciliation” mean?

Over the last several years, our team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers have been exploring what this word means to people in Canada. In doing so, we have come to understand that our relationship to the natural world is an important, yet often overlooked, part of furthering reconciliation.

When thinking about reconciliation we first thought of elements such as truth telling and education, acknowledgement of harm, reparations, healing, strengthening relationships and taking action to address harmful systems. After reading through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) final report, however, our thinking expanded.

We realized that Indigenous Peoples hold a broader view of what reconciliation must involve.

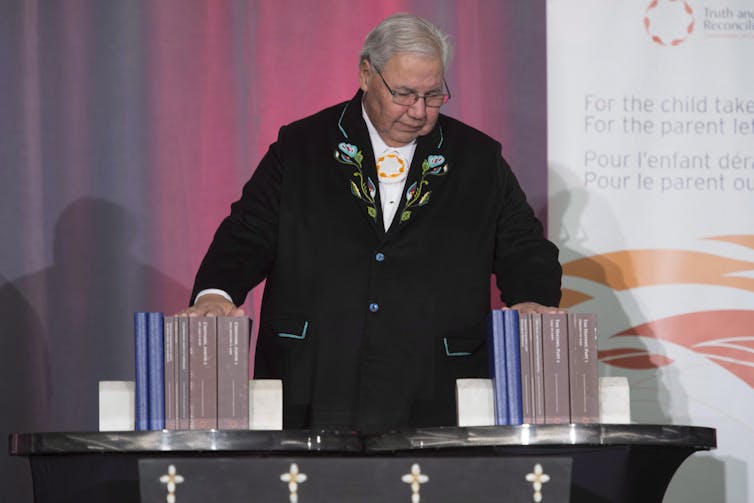

Murray Sinclair places his hands on the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, following its unveiling in 2015. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Indigenous laws and spirituality place high importance on our relationship to the natural world. Reflecting these values, commissioners reported that survivors across the country repeatedly spoke about how “our relationship with the earth and all living beings” are relevant to reconciliation. Survivors felt that if “human beings resolve problems between themselves but continue to destroy the natural world, then reconciliation remains incomplete.”

Our team recognized that if we wanted to come to a holistic understanding of reconciliation, we had to move beyond our conventional, human-centric lens.

Attitudes toward nature, animals and other humans

Both traditional Indigenous knowledge keepers and social psychological researchers have made strikingly similar conclusions about the connection between how people relate to each other and how they relate to the earth and other living beings.

Indigenous knowledge keepers have reiterated how racism and other societal ills such as climate change, pandemics, violence and mental illness are connected. They tell us that our disconnection from the Earth and a mindset based in domination is at the root of these problems and to address these societal ills, we must reestablish our connection and relationship to the natural world.

According to Elder David Courchene, when we “develop the attitude of working together with the common spirit of loving the land, then that love can grow and extend to humanity itself.”

Social psychologists, too, echo this perspective. Researchers have found that those who feel more connected to nature tend to feel more connected to all of humanity. They hold that framing animals as similar to humans not only increases moral concern for other animals, but increases concern for other humans. And social dominance orientation, or one’s preference for hierarchy among groups, accounts for the relationship between speciesism and ethnic prejudice.

Reconciliation, the natural world and moral expansiveness

Considering traditional Indigenous perspectives and social psychological research, we wanted to understand whether people’s support for reconciliation was related to their attitudes toward nature and other animals. And if this was the case, why? To do this, our lab conducted a research study with 233 undergraduate non-Indigenous Canadian students.

At the core of our project is the idea that moral expansiveness, or the breadth of entities a person feels moral concern for, is important for motivating support for reconciliation. People who are more morally expansive tend to feel concern toward a range of entities that seem dissimilar — this might include coral reefs, bees, chickens and members of other social groups.

Researchers have found that those who feel more connected to nature tend to feel more connected to all of humanity. (Ludovic François/Unsplash)

We expected that moral expansiveness would explain the relationship between people’s attitudes toward nature and other animals and their attitudes toward reconciliation. We measured people’s feelings of connectedness to nature, animal-human continuity, or how similar people see animals and humans, moral expansiveness and attitudes toward reconciliation.

Our results showed that people who felt more connected to nature also supported reconciliation more. This was in part because they included more entities within their circle of moral concern. Among women, we also found a similar pattern for animal-human continuity.

So what does this mean? These findings imply that attempts at reconciliation or other social justice efforts may work especially well in natural settings.

Education, a key component of reconciliation, does not have to be limited to traditional classroom settings — it can also take place on the land. It may be possible to expand people’s circle of moral concern and, in turn, promote reconciliation through connecting people to nature. It may also be valuable to educate people on the similarities between humans and other animals.

A call for action

Given our current reality — that we live within a changing and destabilizing climate — it is important to move beyond our human-centric approach to addressing social issues.

To honour the children who never returned home from Indian Residential Schools and further reconciliation, we must protect the children who are with us today.

This means respecting those we are connected to and ultimately dependent on — “all of our relations.” We can do so by supporting Indigenous environmental protection efforts, call upon our governments to take meaningful action on climate change and reduce our personal carbon footprint. Doing so will be good for people and all other life and entities on Earth.

Leora Strand and Katelin Neufeld were part of the research team this article references, and contributed to the production of this article.![]()

Aleah Fontaine, Ph.D. Candidate in Clinical Psychology, University of Manitoba and Katherine B. Starzyk, Associate Professor and Social Justice Laboratory Director, University of Manitoba.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.