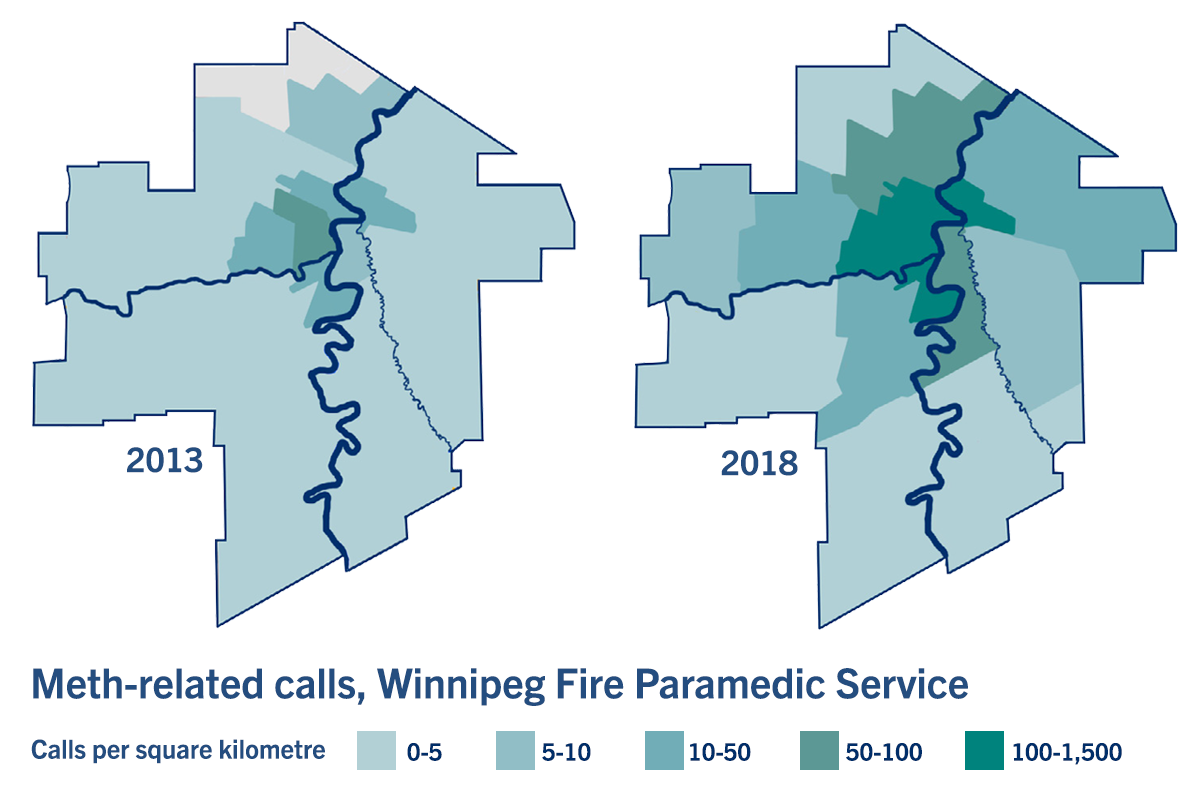

'This is not just an inner-city health issue,' says researcher Dr. Nathan Nickel about meth use in Winnipeg. // GRAPHIC BY MANITOBA CENTRE FOR HEALTH POLICY

Rise in Manitoba meth use seen in soaring rate of ER visits, paramedic calls

The number of Manitobans whose methamphetamine use brings them into contact with the health-care system is climbing dramatically, a University of Manitoba study shows.

From 2013 to 2018, there was a nearly sevenfold increase in the number of Manitobans who had an initial contact with the health system related to methamphetamine (meth) use, researchers at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) in the Rady Faculty of Health Sciences found.

In Winnipeg, the number of emergency-department visits involving meth use rose more than sevenfold (from 134 to 1,001 visits) between 2013 and 2018.

Meth, a highly addictive stimulant, can cause severe health complications, including heart attack, stroke, seizure and death. Users may experience psychosis that causes hallucinations, delusions or paranoia.

The MCHP study of health data aimed to better understand patterns of meth use in the province. It revealed that people who consume the illicit drug are much heavier users of the health system than the average Manitoban.

In Winnipeg, in the year following someone’s first documented use of the drug, they went to a hospital emergency room an average of six times, compared to only one visit every three years by other Manitobans. In the same period, people who used meth were about five times more likely to be hospitalized than other Manitobans.

Those who used the drug also had significantly more doctor visits and more contacts with paramedics.

“Our findings highlight the rapidly increasing need for services among Manitobans who use this drug,” said the study’s co-leader, Dr. Nathan Nickel, associate professor of community health sciences.

“We’ve quantified that meth plays a role in an escalating number of 911 calls and visits to emergency rooms. Recent studies have also documented a dramatic increase in meth-related trips to Winnipeg’s mental health crisis response centre and rising demand for addiction treatment programs.

“By learning more about who uses the drug, we can help the system respond to this population’s health challenges and develop strategies to reduce and prevent meth use.”

To conduct the study, the researchers analyzed de-identified (anonymous) health data stored in a repository at MCHP. They assembled a cohort of about 4,800 Manitoba adults who had used the drug, then traced their interactions with the health system.

“Because we could only track people whose meth use was documented through health-care encounters, we know the actual number of Manitobans using the drug is higher,” Nickel said.

Those who used meth were most likely to be aged 18 to 34. They were about equally split between men and women. More than half lived in low-income neighbourhoods.

In Winnipeg, data from the Fire Paramedic Service showed that in 2013, paramedics were mostly being called to downtown areas for meth-related emergencies. Over the next five years, meth-related paramedic services spread to many other areas of the city. “You can see by the maps in the study that this is not just an inner-city health issue,” Nickel said.

Another key finding, the researchers said, is that people who use meth are far more likely to have one or more mental disorders than other Manitobans. Their rate of being diagnosed with a mood or anxiety disorder, for example, was three times higher than among other Manitobans.

“Although we don’t know from the data whether their meth use preceded their mental disorder or vice versa, our findings indicate that caring for people who use meth is complex because their challenges are often multi-layered,” said Dr. Mariette Chartier, assistant professor of community health sciences and co-leader of the study.

“Studies have shown that people’s life circumstances can predispose them to turn to meth as a way of coping. As Manitoba’s health-care planners work to support people who use meth – and relieve the growing burden on front-line services that we’ve documented – it’s critical to address underlying factors that influence both mental health and substance use, such as poverty, insecure housing, racism and trauma.”

The researchers will continue to examine meth use in a project funded by Health Canada. They plan to document the lived experiences of Manitobans who use meth and study their health outcomes.

The full study is available online.