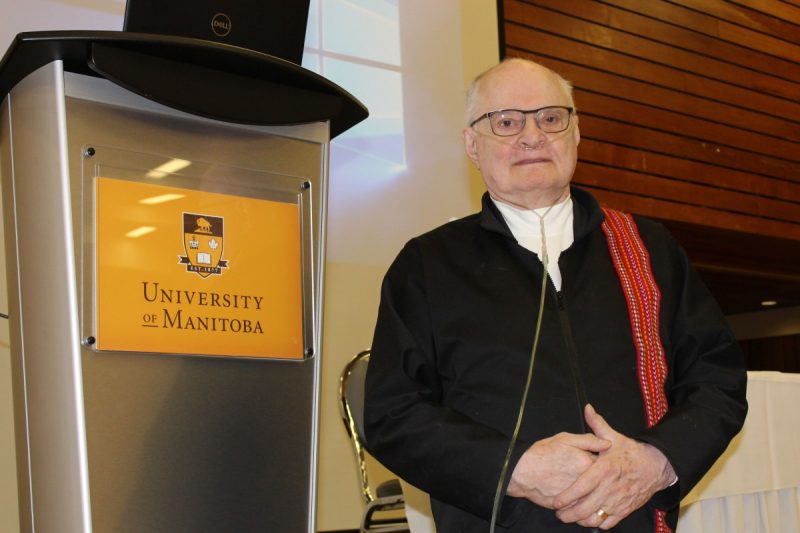

Fred Shore demonstrates the complexities of loading a musket during your buffalo hunt.

Indigenous storytellers share history and experience

Accessing culture through stories

Indigenous storytellers share traditional experiences and history, in a way that is personal, accessible, and educational.

On March 25, eager listeners gathered for the second of two sessions of Indigenous Storytelling: An Alternative Path to Understanding Truth and Reconciliation presented by the Access Program and sponsored by the Indigenous Initiatives Fund. The first was held on Feb. 13.

The March event featured three storytellers and elders: Fred Shore (Métis), Martha Peet (Inuit), and Wanbdi Wakita (Dakota).

Fred Shore, Métis storyteller, elder and professor of Native Studies at U of M

Stories to teach

“My stories come out of my teaching,” says Fred Shore, Métis storyteller, elder, and professor of Native Studies at U of M. “When I started teaching, I discovered history could be boring. So I started telling stories to make it interesting.”

But he doesn’t make it up. “I think stories have to be both interesting and verifiable. I draw from oral history I have collected for years, and read between the lines in history books, to tell an interesting story.”

For example, in one story, he explores how you hunt buffalo on horseback with a muzzleloader. And the process is not an easy one. Imagine riding a horse at 35 mph in a herd of buffalo, bouncing around, trying to get the ball and powder down the barrel to load your gun. Of course, Shore has not actually done this himself, but he collected the details to tell us how it’s done.

“In exploring the logistical organization of the buffalo hunt, my objective is to show people the Métis were highly organized and really knew how to do things. A lot of people assumed the Métis were an ignorant bunch of savages. But they went after buffalo to bring back pemmican and sell it to the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Northwest Company for cash. My purpose is to show the economic foundation of the Métis Nation.”

For Shore, storytelling is about putting the details of people’s experiences together and adding a little excitement to it, so “you can almost hear the horses pounding down the road.”

It’s important to talk about these things, Shore says. “A story is being used to teach about who the Métis are, where they come from, and why they are the way they are.

“I love telling stories. That’s my thing. Where did I learn to do that? There are many teachers in my family. I am also part Irish, so, of course, I have the gift of the gab.”

Martha Peet, Inuit elder and storyteller

Personal experiences

For Martha Peet, Inuit elder and storyteller from Taloyaok, Nunavut, telling stories is about sharing her own experiences and the traditional Inuit way of life.

Taloyaok was founded in 1948 when the HBC established a trading post. Five nomadic families moved in, including hers. Peet was born in 1950. “I was there from the beginning. I lived in an igloo in the winter and a tent in the summer. My job as a child was collecting cotton in the summer, for the wick on the seal oil (soapstone) lamp (fueled by blubber). I always had chores. I carried water twice a day from the lake. I made bannock and tea. We boiled our meat, seal and caribou,” she says.

A storyteller for over 30 years, Peet enjoys sharing stories about her life, where she is from, and the Inuit way of life of years ago including the importance of animals and traditions.

Martha Peet in her mother hubbard.

Martha Peet, with the coat her mother made for her.

The past

“I tell stories from my past. It is so important to keep the Inuit way of life strong, and keep it going. I never stop being homesick for being on the land, picking berries and plants, camping and fishing. It’s what we grew up with, what parents teach their children. I speak from my experiences. The ways the nomads in the areas, including my parents, went seal hunting, spring fishing, hunting caribou in the winter. They followed the animals year-round.”

When people hear her stories, Peet says, they are surprised but happy to learn how traditional her early life was, even as recently as the 1950s. “In the 1950s, we were living in igloos and eating traditional foods all the time. It is like yesterday to me.”

Of course, now the community is modern and home to 1,000 people. Many kids speak English, but many also still speak their own language with their parents, and parents continue to make caribou coats and mitts. Yet, eating habits have changed and there are more illnesses, she says.

“Storytelling is important because it’s the way people learn about our past, how I was born and raised, the environment, the hardships and pleasures of my experience up in the arctic. There are different plants and berries that don’t grow here. I long for those. When you get hungry out on the land, you eat plants and roots.”

Peet learned many of her grandmother’s stories through her sister, for she was very young when her grandmother died. “I remember the values taught to me. They were set into my life. I remember my dad hunting, my mom sewing. I always remember. Everything is so important. I was taught how to carry a rifle. The lessons stayed with me my whole life.”

She also retains fluency in her language, by continuing to speak with other Inuit people, doing translations, and keeping up-to-date. “I keep researching for new words for new concepts that did not exist before, like global warming. There are some things you can only teach on the land in your own language.”

Wanbdi Wakita, Dakota elder, storyteller, and Access Program Unkan (Grandfather)-in-residence

An important tradition

Wanbdi Wakita, Dakota elder, storyteller, and Access Program Unkan (Grandfather)-in-residence, notes the importance of the storytelling tradition and bringing it to campus. “I am pleased this community is starting to recognize Indigenous people still have a big contribution to make to this world, and there is an interest to listen to the stories.”

The Access Program at the University of Manitoba provides holistic support to Indigenous, newcomer, and other U of M students, empowering them on their path to success.