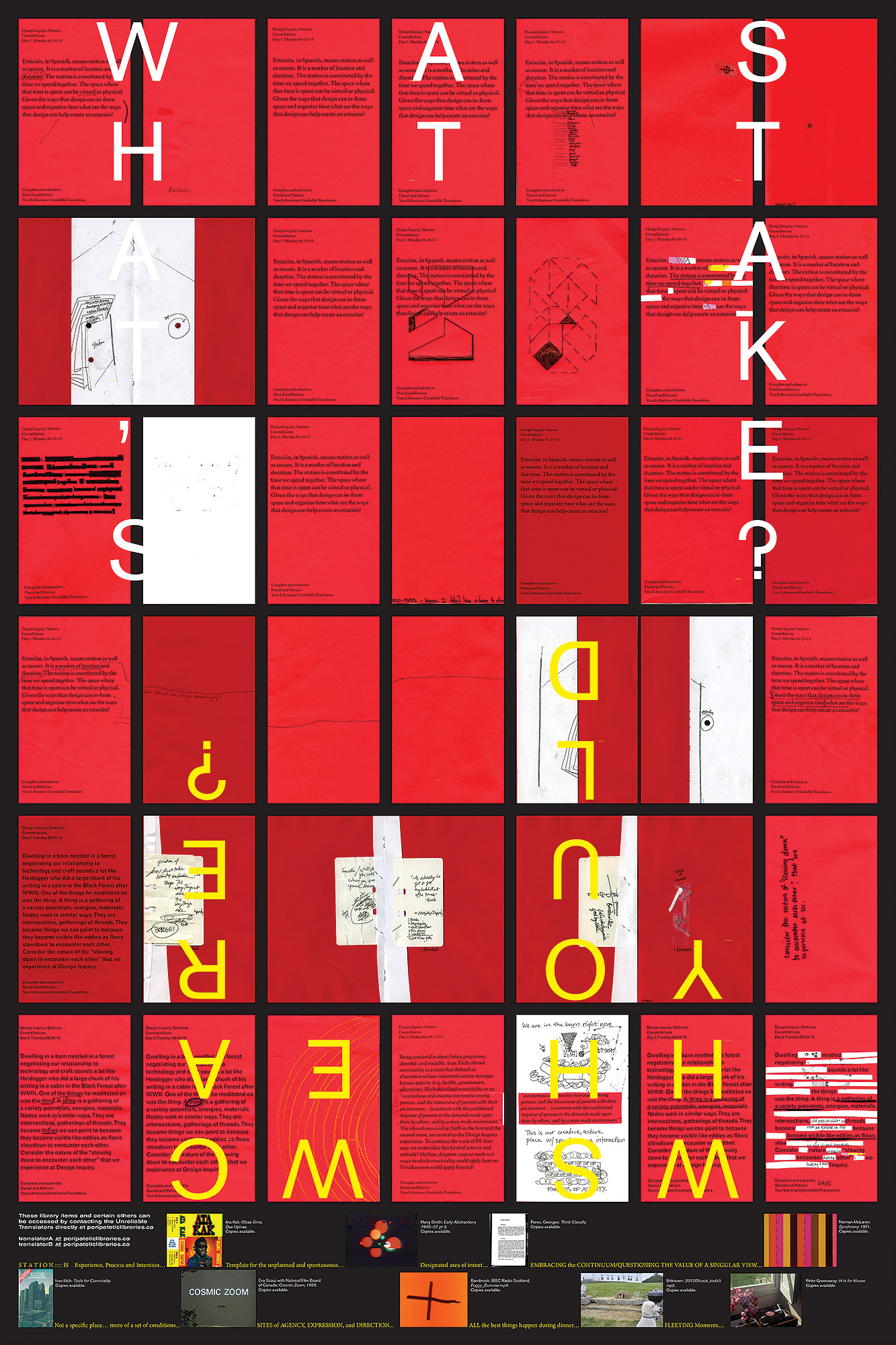

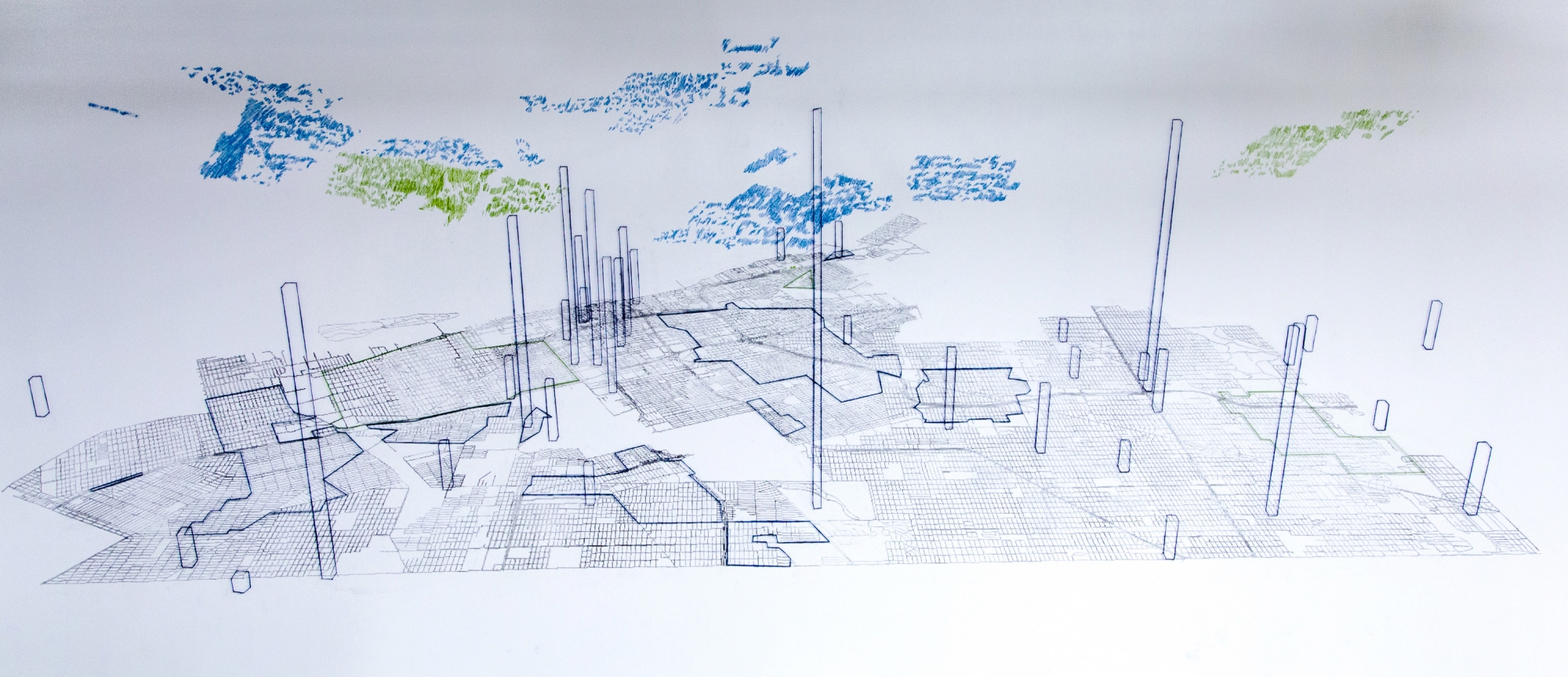

Public Design Unit (PDU) I am here: Mapping Detroit Water Shut-offs Projection Map Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit Photo: PDU

Freehand

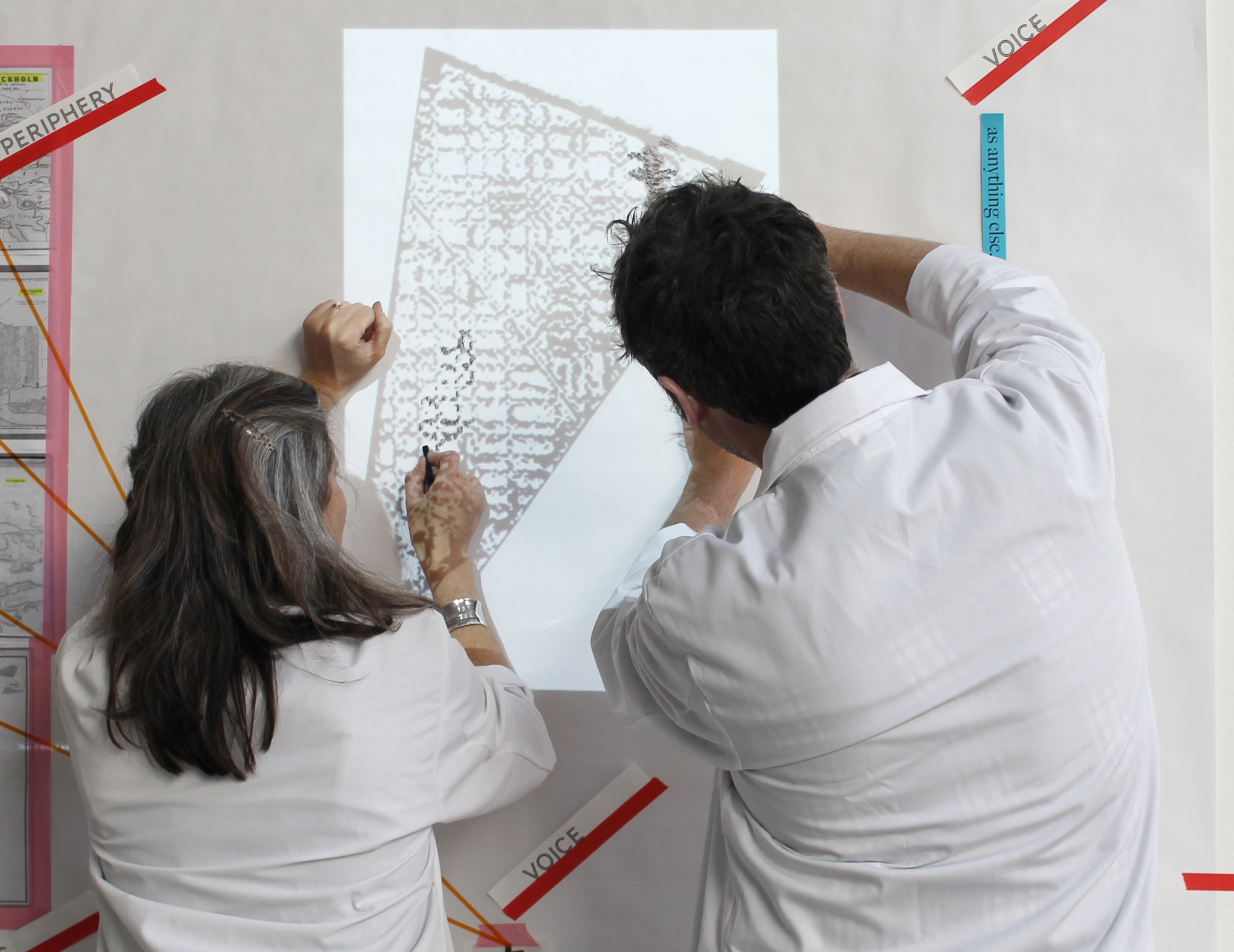

Different Data Nordic Design Research Conference Exhibition Stockholm, Sweden | Photo: Joshua Singer,

Different Data

It’s pervasive to the point of invisibility. From the daily media we view to the products we consume, from the clothing we wear and the spaces we inhabit to the vehicles that transport us on the road systems we use and the weather data we rely upon in planning our day, design plays a role in almost everything.

However, in its seemingly happily innocuous existence, it goes largely unnoticed. According to design professor Daniel McCafferty, “Design may be one of the most ubiquitous, yet least discussed—and possibly [least] understood—modes of communication.”

Public Design Unit (PDU). I am here: Mapping Detroit Water Shut-offs (detail) Projection Map Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit | Photo: PDU

Design is commonly credited with providing solutions, offering efficient and creative responses to challenges from the everyday to the profound.

And design purports to understand itself as a problem-solving enterprise, he underscores.

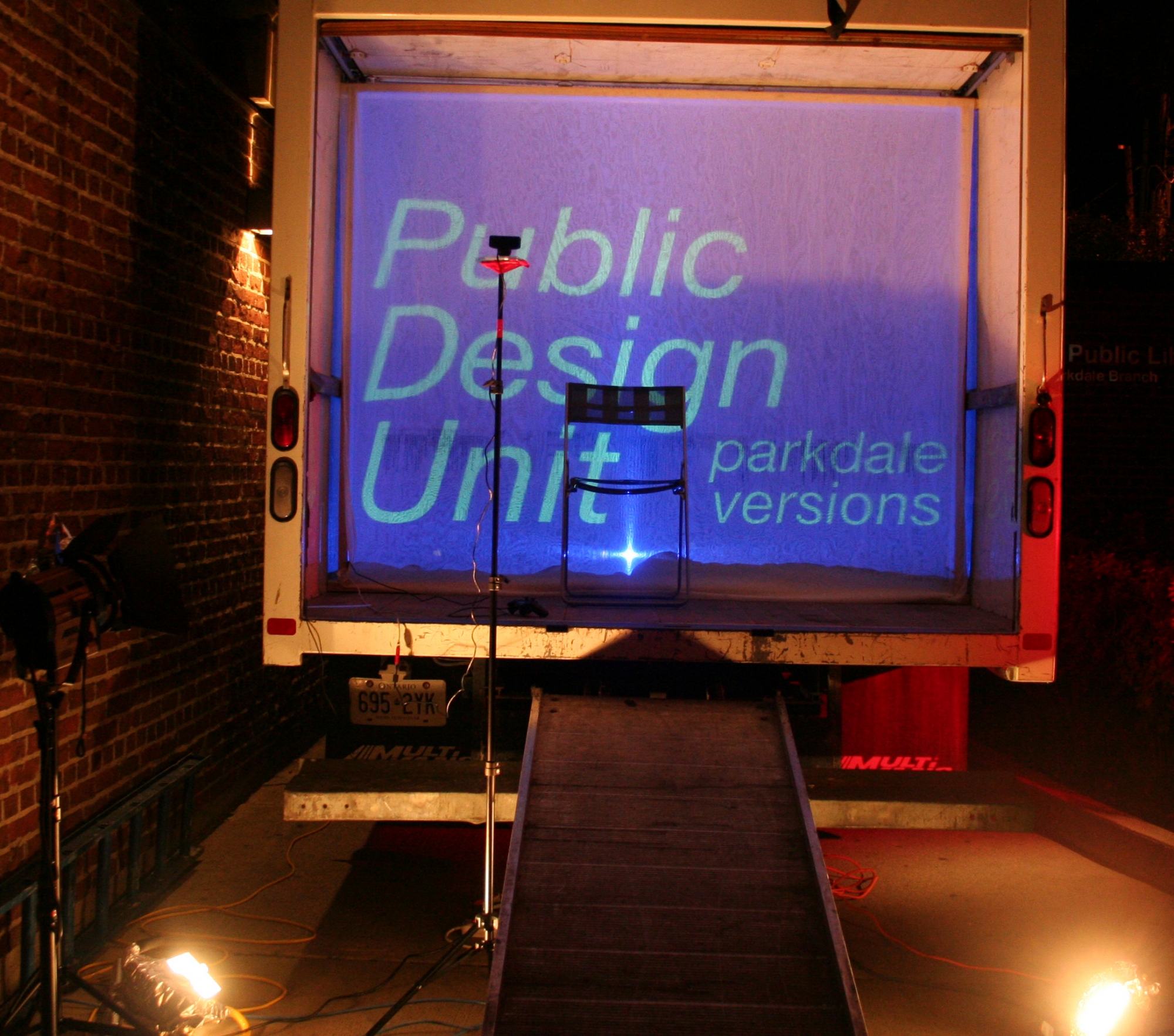

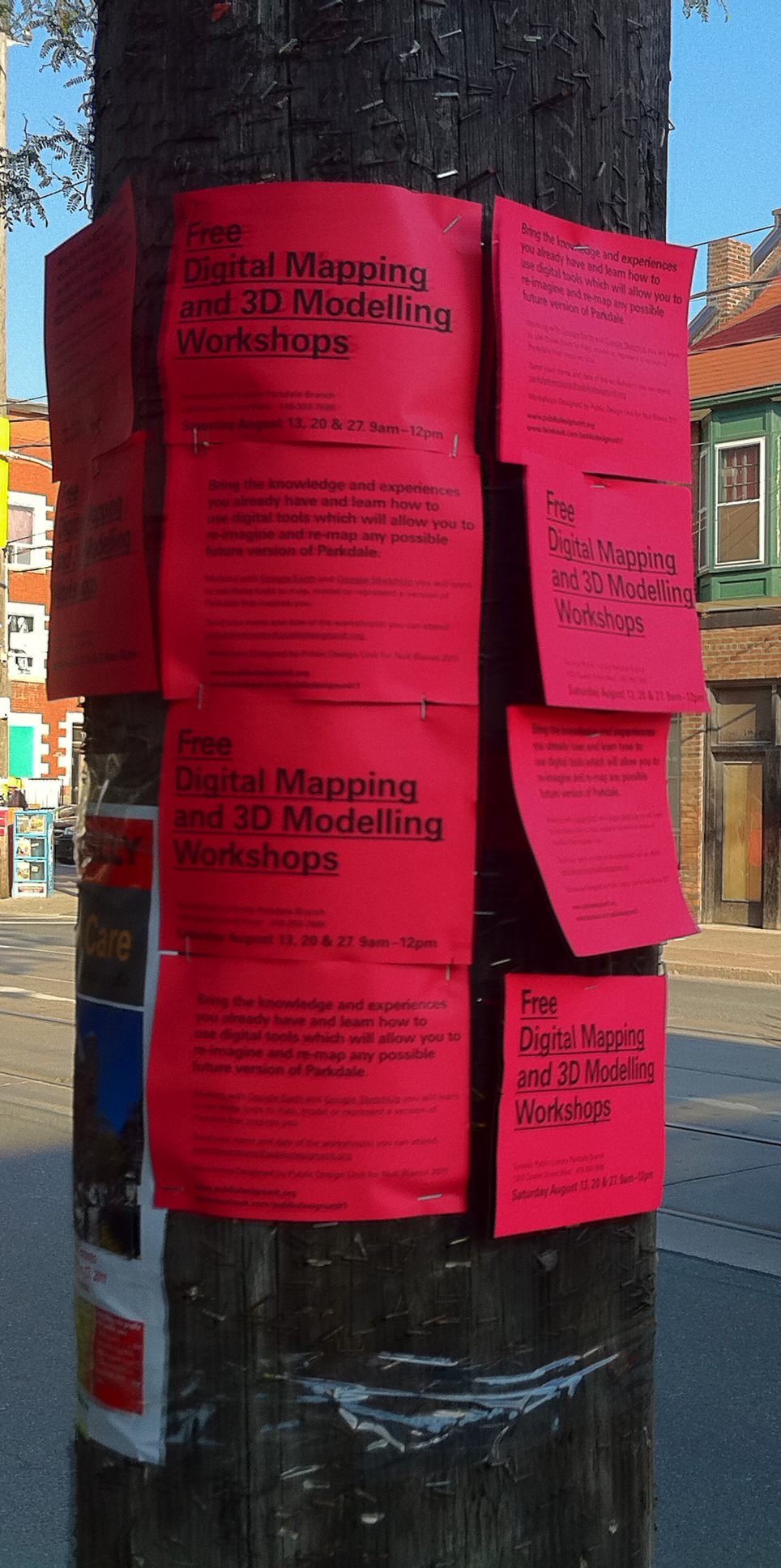

Public Design Unit Parkdale Versions, Peripatetic Libraries Toronto, Scotiabank Nuit Blanche | Photo: PDU

‘I feared that when designers see themselves as providers of solutions … that they bring a sense of right and wrong to the situations they are asked to consider. I think today it is fundamental for designers to be humble.’ – Daniel McCafferty

The common equation, for McCafferty, evinces a potential hubris about what problems are and how they can be solved (even best solved)—hubris that made him increasingly uneasy—and shrouds a number of other equally troubling issues. Not least is that design is too readily positioned as a tool of consumerism, put in service to commerce, money and power—another aspect that disquieted McCafferty, who has a history of involvement in punk and social activism. These opaque, underlying assumptions can limit design to an instrumentalized practice and a linear procedure rather than unlocking its potential as a process, he adds.

‘The bias works to portray design as a tool for commercial activity, one where risk, chance, duration, uncertainty, play, have little worth.’ – Daniel McCafferty

So, what if, instead of propping up the problem solver definition, design did something else entirely? What if instead of offering objective answers, design was a method of engaging with and caring about others, of discerning problems? What if design freed itself from its conventional context and became a way of thinking, a way of questioning and gathering insights?

Adding inquiry, self-reflection and relationship to design is what McCafferty’s research, pedagogy and practice are all about. He calls it “problematizing” design.

‘Problems solved will always yield new, unforeseen problems arising from any given solution. The social world is a relational world.’ – Daniel McCafferty

Problematizing Design: ‘Designer As’

To shift the problem-solving equation to something more generative, Dan McCafferty looked at alternate ways of understanding design in a project entitled “designer as.” Most recently, he’s been adding the word “gardener,” and thinking about design as nurture.

It’s easy to see the appeal of this formulation. Instead of defining—and containing— a problem by capping it with a clean and simple solution, it releases entirely different possibilities for design—and for ways of thinking about problems and objectives— opening the field for engagement, cooperation and cross-pollination, for spurring productivity and shared growth.

‘The project asks what would design do, whom would it serve, how would it change, if the metaphor was designer as gardener, design as nurture. The work produces results that are naturally vulnerable to dismissal; they are contingent on a willingness to reflect, consider. They are merely proposals. They are, of course, not solutions.’ – Daniel McCafferty

He says the project speaks to an intensifying desire by some within design to sustain its role as “an agent of change,” but pushing beyond its usual boundaries in order to better address today’s complex problems and foster collaborations in areas of social and health services, data science and more.

It aims to critically engage from a decolonial and anti-racist perspective, refashioning design pedagogy and practice in ways that counter Eurocentric norms, including amplifying a diversity of voices rather than replicating existing structures and attendant privilege of the few with power, which design could quite easily be accused of doing, he says.

In 2017/18, McCafferty created the Indigenous Designer in Residence program so the School of Art could host Sébastien Aubin, an Indigenous graphic designer and artist from Montreal. During a six-month residency, Aubin’s research and body of work culminated in the exhibition “Sébastien Aubin: no brighter at the middle” at the School of Art Gallery. Aubin also collaborated with students and faculty, and helped open up discussion on the decolonization of curriculum and research practices.

Impact Beyond Problem-Solving

After grad school, McCafferty cofounded a design research group called Public Design Unit (PDU) with other similar-minded practitioners. Working outside of the template, the project broadened design’s impact.

The project deliberately confounded traditional frameworks, from timeframes to workspace, opening up the design process to the public by setting up at the local library. The group worked on one long-term project rather than several, and lengthened its time in the community—“recognizing that designers are often brought in to solve a problem, then they leave, without understanding the impact of their work, or seeing if and how it has changed anything,” says McCafferty.

PDU was interested in applying a critical approach to design and design process. This meant that we wanted to work against every convention in design that we could.’ – Daniel McCafferty

Throughout the project, the designers were accessible to the community and their work was visible. After spending several weeks getting to know the neighbourhood better and speaking to the people who lived there, the group ran community workshops.

They emphasized participation and local vernacular over designer control, using open source software and default typography and preferring less technically specialized tools such as Google Earth.

‘When design operates in service to capitalism, exclusively, the problems it solves … are related to what [philosopher and sociologist] Bruno Latour might call matters of fact—rather than to matters of concern.’ – Daniel McCafferty

McCafferty uses an open source programming language called Processing that allows the user to create generative videos, diagrams, visualizations and data videos. The politics and the ethos of open source projects match his DIY/punk past; ideas about disruption present in his current work stem from those earlier days.

“The appeal of this programming language and learning how to write code for creative exploratory and visual purposes, rather than for functional practical outcomes, is that it forces a rethink in terms of how work is developed and visualized,” he says.

The impulse is one that seems to come to him naturally.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.