Breast Cancer Quest

When Yvonne Myal [M.Sc./83, PhD/89] was a young child in Trinidad, she was distressed by seeing an elderly neighbour in terrible pain.

“She was dying of breast cancer at home,” Myal recalls. “I asked my mother, ‘Why don’t they take her to the hospital?’ But they couldn’t do anything for her. That really made an impact on me. Breast cancer has touched so many of our lives.”

Myal immigrated to Manitoba in her late teens and completed an honours degree in biology at the University of Winnipeg. She then came to UM to earn her master’s and PhD under the mentorship of Dr. Robert Shiu, a breast cancer researcher. She was greatly inspired by the potential of laboratory science to unlock the mysteries of the disease.

“I thought, ‘I can make a contribution here,’” the molecular biologist remembers. “This has been my life, and I’m still excited about doing the research.”

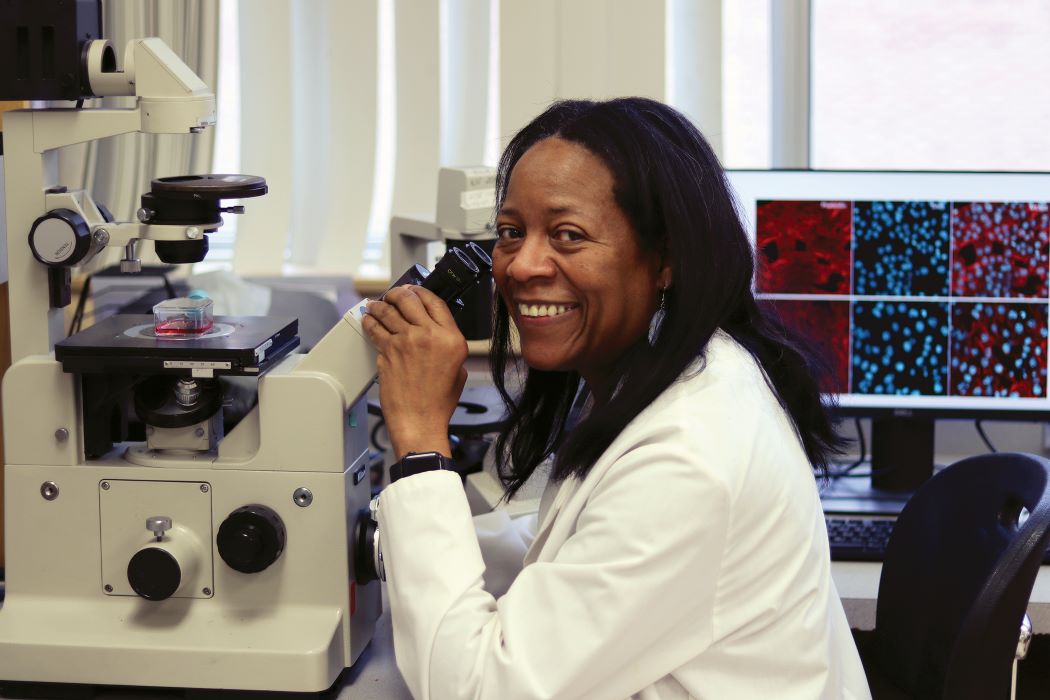

Now a professor of pathology who is cross-appointed in physiology and pathophysiology, Myal recently marked 25 years as a principal researcher in the Max Rady College of Medicine. She is also a senior scientist at the CancerCare Manitoba Research Institute.

For a quarter-century, her lab has worked to pinpoint and isolate biomarkers that are specific to breast cancer and to understand their role in the progression and metastasis of the disease.

Her research is currently funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the Cancer Research Society and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Since 2016, she has served as the UM delegate to the CIHR.

Myal’s long-term focus has been on two proteins that play roles in breast cancer. Notably, her lab has been a world leader in studying the human prolactin inducible protein (PIP).

“The gene expression of PIP occurs in more than 90 per cent of breast cancers,” she says. “Our lab is particularly studying it in triple negative breast cancer, a type that is very aggressive and has no current treatment.”

Myal was a doctoral and postdoctoral researcher, then a research associate, from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s – a period when cloning genes (isolating them and determining their sequence) was a laborious “from scratch” process. Still, she has wonderful memories of that era.

Her mentor, Shiu, had himself been mentored by Henry Friesen [B.Sc. (Med.)/58, MD/58, D.Sc./98], a renowned scientist who had discovered prolactin, a hormone involved in breast development and lactation.

Friesen’s lab, which was just down the hall from Shiu’s, had a huge team of postdocs from all over the world. “It was like one big research family,” Myal says. “Every day was an adventure.”

Myal became the first scientist in the world to clone the gene that produces PIP – a project that took her four years. Then she and Shiu were the first to develop a transgenic mouse model for PIP, meaning that they successfully manipulated the genes of lab mice for experimental purposes.

Myal and her team went on to genetically engineer the first knockout mice (mice with an inactivated gene) for studying PIP. More recently, they used CRISPR gene-editing techniques to create additional mouse models.

One of Myal’s important discoveries was that PIP plays a positive role in the immune system, defending the body against invading organisms. “We were the first to show that in saliva, PIP binds to invading bacteria and inhibits their spread in the mouth,” she says.

She went on to demonstrate that PIP inhibits the growth of primary tumours in the breast.

“But when breast cancer cells that have PIP leave the breast and travel to the lungs – which happens in triple negative breast cancer – they divide rapidly, compared to the cancer cells that don’t have PIP.

“We showed that in the lungs, the body’s immune system no longer has any impact on the multiplication of these cancer cells. PIP actually makes the cancer spread faster in the lungs. There are still so many questions to be answered about this protein.”

Looking back on the 1980s, Myal says many women in science faced difficult choices. At UM, grad students were strongly encouraged to move to more “prominent” universities for their postdoctoral work. But Myal’s husband had a career in Winnipeg, they planned to have children (their son and daughter were born in 1993 and 1995), and they decided to stay in the city.

When a tenure-track professorship opened up in the pathology department, Myal didn’t think she was qualified. “You kind of feel you’re not good enough because you didn’t go elsewhere,” she remembers.

Fortunately, a mentor urged her to apply. She got the job and founded her lab as a principal investigator in 1997. She has been recognized with many honours, including a 2011 YMCA-YWCA Women of Distinction Award in the category of science, technology and the environment.

Myal’s lab team has always been small and highly collaborative.

“Teamwork, mentorship and collaboration have served me so well,” she says. “Every time we get a paper published or one person has some success, we celebrate as a team. That’s the philosophy I’ve passed on to my students.

“I’m so proud of the accomplishments of my trainees. Many of them are excelling in health care, research, industry, and being recognized nationally and internationally.”

Having spent 40 years in Bannatyne campus labs since her master’s days, Myal values the university for its supportive research environment and its intergenerational chain of mentors and mentees.

“I’ve been very privileged with the great opportunities that U of M has afforded me,” she says.