Advancing Antimicrobials

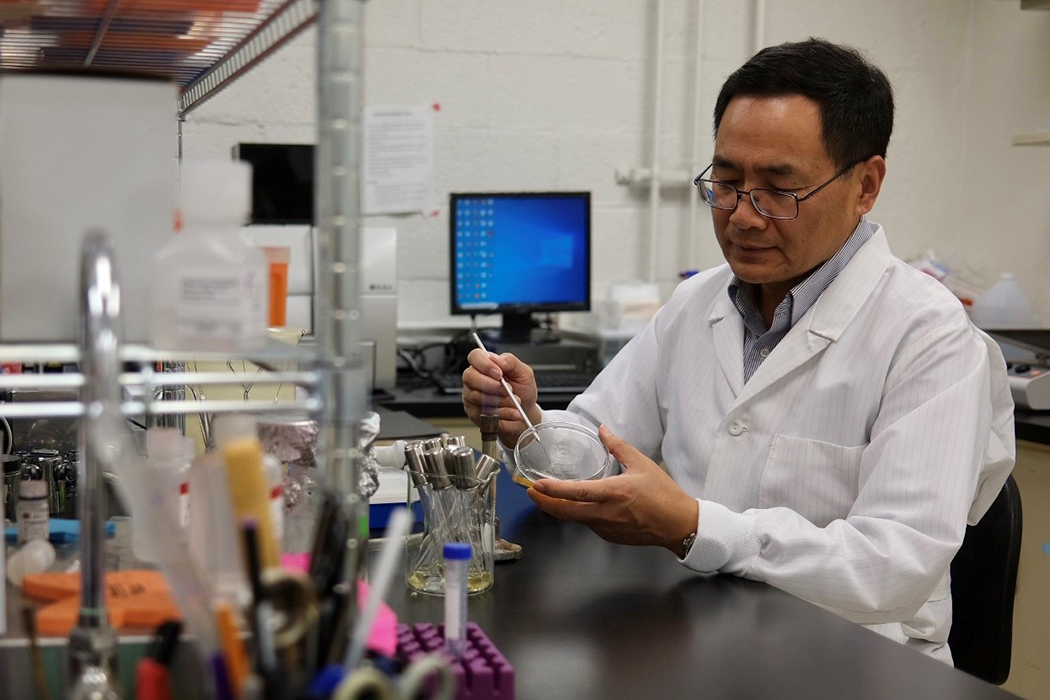

What Dr. Kangmin Duan studies is microscopic, but the problem he’s working on is colossal.

The microbiologist researches how bacteria cause infectious diseases and become resistant to antimicrobial (antibiotic) drugs.

The increasing resistance of bacteria to antibiotics poses a global health threat, he says.

“Antibiotics used to be wonder drugs. But now, because of antimicrobial resistance, the treatments aren’t working in an increasing number of cases. We need to find new medicines.”

The Chinese-born Duan is a professor of oral biology in the Dr. Gerald Niznick College of Dentistry, with a cross-appointment in medical microbiology and infectious diseases in the Max Rady College of Medicine. He is also a researcher with the Children’s Hospital Research Institute of Manitoba and belongs to the Manitoba Chemosensory Biology Research Group.

Many of his studies in journals such as Molecular Microbiology have shed light on Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a multidrug-resistant bacterium that causes serious infections, such as those in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis.

New antibacterial drugs that work in standard ways will inevitably fall victim to antimicrobial resistance, Duan says. So his lab is taking an alternative approach: targeting the mechanisms by which bacteria cause disease. The goal is to develop medicines that render bacteria harmless instead of killing them, because it’s the drive to survive that causes bacteria to become drug resistant.

“We aim to develop drugs that inhibit the virulence of disease-causing bacteria, rather than the viability,” Duan says. “To do that, we’re experimenting with ancient herbal medicines.”

Duan grew up seeing traditional Chinese medicines successfully used to treat symptoms that resemble those of infectious diseases, from skin problems to diarrhea.

Researchers have found bacteria-killing agents in these herbal remedies, he says, but so far none has been developed into an antibacterial drug because of low efficacy or high toxicity.

Traditional Chinese medicines seem to work, Duan says, and he wants to understand what mechanisms are at play. A study he co-authored last year, published in Antibiotics, looked at the effectiveness of a chemical compound found in Chinese herbs in reducing “virulence factors” of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The compound significantly reduced mortality in mice infected with the bacterium.

“These results are encouraging,” he says. “This compound is a promising drug candidate.”

Duan started his scientific education at China’s Northwest University. He then moved to Australia to earn a master’s and PhD at the University of New South Wales.

He was a professor at Northwest University and an adjunct professor at the University of Calgary before joining UM in 2010.

He says he enjoys being part of the oral biology department at UM because of the collegial atmosphere and the researchers with eclectic interests.

Alongside his antimicrobial research, he is currently studying how bacteria interact with each other in microbial “communities,” and how they interact with human hosts.

He is also working on a project with oral biology colleagues to understand whether tooth resorption – the progressive loss of the inner tissue of teeth or the material covering teeth’s roots – is associated with microorganisms in the mouth.