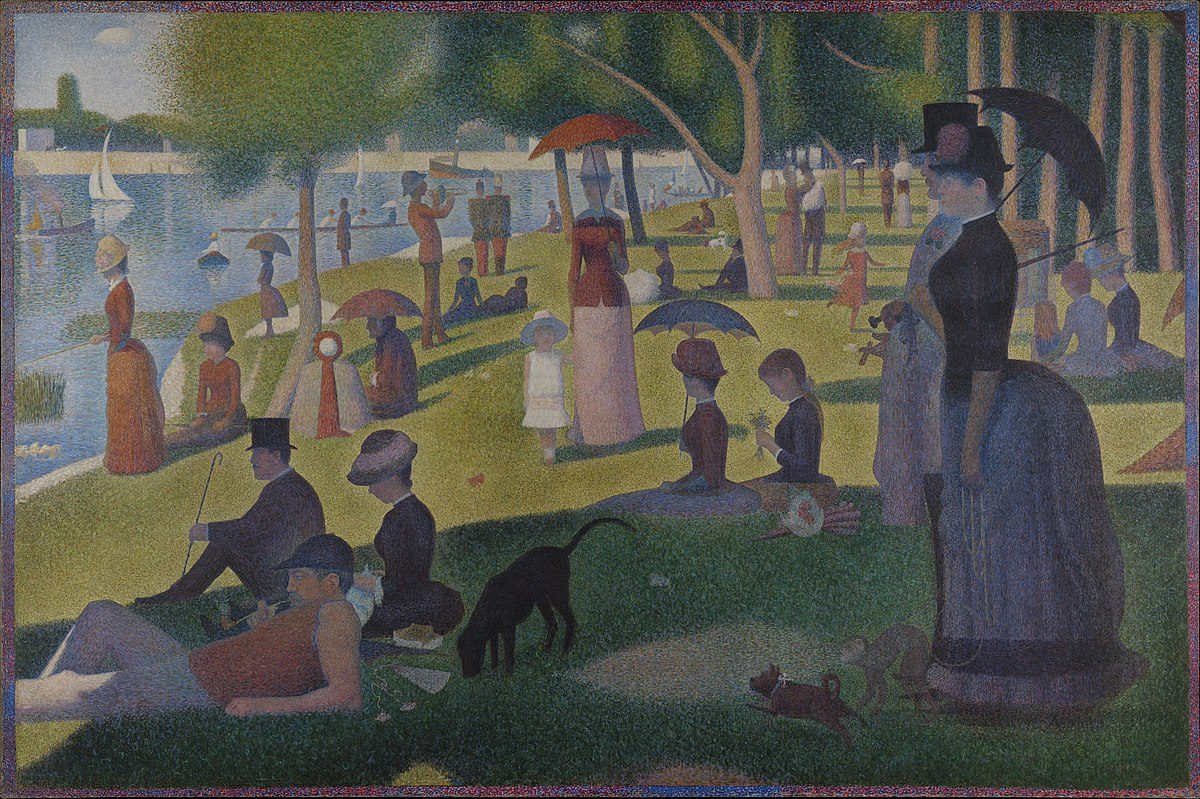

A Sunday on La Grande Jatte by By Georges Seurat (1884), courtesty of the Google Art Project

Connecting the dots: Powerful research tools locate trends, improve care

If you stand too close to a painting by pointillist artist, all you’ll see is a collection of dots.

But step back far enough and you’ll see how each one – meaningless on its own – fits with the others to make up a greater whole. Patterns emerge and the picture clears. The more dots you have, the sharper the focus. For a researcher like Alexander Singer (CCFP/09), director of the Manitoba Primary Care Research Network (MaPCReN), medical data works the same way.

As part of the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN), Canada’s first multi-disease electronic medical record surveillance system, MaPCReN offers researchers like Singer the ability to digitally extract information from patient files across the country.

When you connect all the dots, patterns of disease emerge, along with trends in care delivery and prescribing. Primary care data from clinical practices is a powerful tool that is changing the face of research, says Singer.

One of the biggest changes with using health data is speed and volume, he says. When he was a resident, he spent two weeks working in the basement of the Health Sciences Centre working on a chart audit. “There were hundreds of charts,” he recalls. “I had to look through about 300 to find the 90 that were eligible, then take all the information out of those charts.” Then came data analysis, with additional time to write it up. “When you do that kind of work manually, it’s very time consuming.”

Now an associate professor, Department of Family Medicine, Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, he typically works on multiple projects all at the same time, right from the comfort of his own desk. His study on antibiotic usage includes over 80,000 patients, but it took a review of 250,000 charts to find the relevant prescriptions. Because they were digital, processing the data took less than a day. “It’s not that this study of that kind was impossible before,” he points out. “It’s hard to get big numbers – it takes a lot of money and it’s very hard to scale.”

The practical implications of MaPCReN are profound, says Singer. With the ability to review patient care, right from testing to diagnosis, along with any prescriptions written and the outcomes of care, researchers can help healthcare providers improve the way they practice medicine. “We can report back and say, ‘Did you know you’re doing lot of antibiotic prescribing for conditions that look like they’re viral?’” The opportunity for feedback allows for quality improvement, which is a benefit to both physicians and patients.

Long-term, Singer hopes MaPCReN can play a role in helping to relieve an overburdened healthcare system by getting out ahead of chronic disease. “Rather than saying we need to constrain a resource, what if we could treat the problem upstream?” he says. For example, end-stage kidneys disease requires dialysis multiple times per week. “We know diabetes and hypertension drive the need for dialysis. If we can improve their management, that could improve the health of our patients, but that also improves the health of the system if we can avoid costly and burdensome treatments by preventing progression of the diseases that cause them.”

Ultimately, Singer believes what MaPCReN can deliver is a big-picture view of health in Canada, with a focus on doing better at all levels. “If we do that we’re going to see better outcomes and healthier communities.”

Dr. Alexander Singer (CCFP/09)

Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences; Director, Manitoba Primary Care Research Network (MaPCReN)

Research: Use of Primary Care Data, Informatics and Quality Improvement