Radar technologies were used to aid in selecting ice core location. The radar penetrates the ground to detect different layers of ice. This process is not as precise as the ice core itself, but since ice-core drilling is a long, expensive, endeavor, and time and resources are limited, reconnaissance is done far prior to any drilling. Radar is used to get a rough idea of the ice layers in the region which aids in site selection.

How have sea ice and climate varied in the Canadian Arctic during the last 20,000 years?

Follow along as scientists drill ice cores in Nunavut to find out

To answer this question, Professor Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, Canada Excellence Research Chair, and team are looking to drill an ice core on Müller Ice Cap, Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut. You can follow along as they post updates to their blog.

Measurements of climate conditions in the past are critical context for current climate change. We know that the Arctic is warming much

Müller ice cap in Nunavut, Canada .

faster than the rest of the planet. This warming is destabilizing ice both on land (glaciers and ice caps) and on the ocean (sea ice). Sea ice in particular is important for people and animals who live in the north, as it affects travel and the ability to hunt and fish. Ice cores are some of our best tools to determine how ice and climate have varied over long time periods.

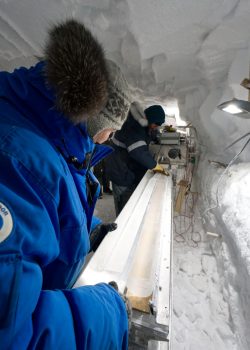

An ice core is a long, thin stick of ice drilled through a glacier or ice cap. Over the course of months or even years, hundreds or thousands of 2–3 m long, 10 cm diameter sections of ice are drilled and brought to the surface. The result is a record of the ice through time; at the top, there is fresh fallen snow just turning to ice while at the bottom the ice is composed of snow that fell thousands of years ago and of air that was trapped in that snow. After all this ice is drilled, it is shipped back to laboratories for detailed analysis.

By measuring properties of the ice itself, and of air bubbles trapped in the ice, there are well developed methods to determine both what the atmospheric composition was and how warm the atmosphere was at the location of the ice core in past. Recently, proxies have been developed to determine sea-ice conditions in the area of the ice core at the time the snow fell, providing a critical missing piece of information about the climate system in the past.

The Müller ice core will be drilled through about 600 m of ice on Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut. The core will be unique because of its high latitude and elevations. These conditions combine to create a record of ice that has not been contaminated by melt and contains old ice. Since the core will come from so far north, the sea-ice proxies in the core will give information about past conditions in the Arctic Ocean itself. This information will help determine if the current declines in sea-ice extent in the main basin of the Arctic Ocean have any precedent.

Before investing the time and money to recover an ice core, it is important to find an area with thick, undisturbed ice. Currently, Dr. Dahl-Jensen and a small team are on their way to Müller Ice Cap to measure its thickness using radar. Over the course of three weeks, they will drag a radar around the surface of the ice cap, identifying where the ice is thick and well layered. They will measure how much it snows in the area in order to determine how old they can expect the ice to be in the core. You can follow along with their progress at mullericecore.org.

With the groundwork laid this spring, a larger team will go the ice cap for three months in 2024 to recover the ice itself.

A large ice coring drill similar to that which will be used on Müller Ice Cap. The drill recovers about 3 m of ice with every trip down the hole, recovering about 30 m per day when operations are running smoothly.

Dr.Dorthe Dahl-Jensen examines an ice core .