Newdale soil, Manitoba's official soil.

Dec. 5 was World Soil Day. It deserves celebration

This story was originally published on May 5, 2015.

Soil is not itself alive, but is made of life and gives life. Ancient in some locales and days old in others, no matter where it lays it’s the cradle of creation for all terrestrial life – not figuratively, but literally, in the grand biblical way.

“Just don’t call it ‘dirt.’ The thing about ‘dirt’, it doesn’t give respect to something that does so much for us. It’s demeaning to soil,” says Mario Tenuta, professor of soil science in the Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences.

“Dirt is something in your house you pick up with a vacuum cleaner. When you’re outside, the stuff the plants are growing in, the stuff that sustains life, is not dirt by any means. Give it some respect, the most respect. Even creation stories, such as in the Bible, start with ‘from earth to earth, dust to dust’ – well, it’s unfortunate it says dust because it should be from soil to soil, but they are giving you the incredible importance of soil right up front.”

The United Nations General Assembly has declared 2015 the International Year of Soils, offering us a chance to celebrate this remarkable substance.

Soil is forgivably overlooked because its wonders exist on a scale we can’t see. You can dive into oceans and see new worlds. Visually, you fall in love. With soil, you can’t do that. You can’t walk into it like a forest. You always need microscopes to see its beauty and so the masses miss the fun.

And fun it is. Humbling too. Perhaps of all Earth’s substances, none offers such a lesson in humility.

Biologically: Ceaselessly toiling in soil’s darkness through every hour of every age are varieties of life so diverse and abundant they bankrupt the imagination. All live in constant warfare too. The bacteria alone build ferocious armories, and humanity desperately needs access to them if we wish to continually develop drugs to defeat antibiotic-resistant superbugs. But where to begin?

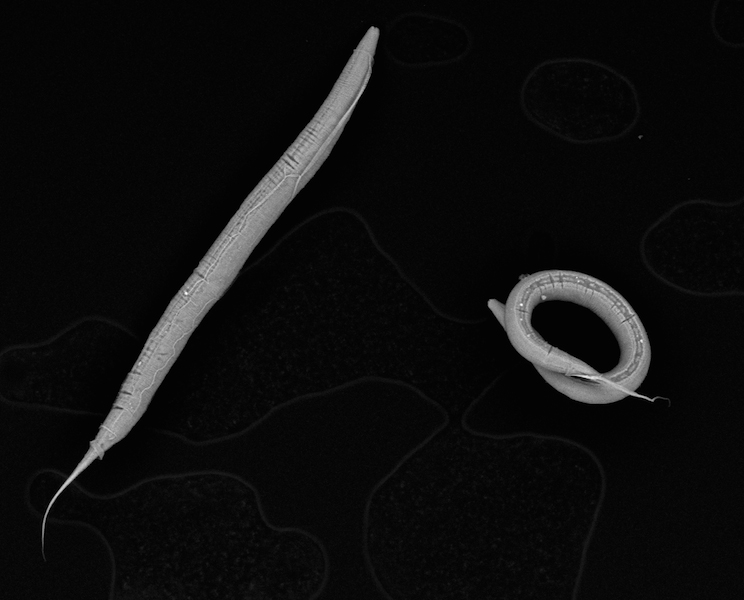

Scoop some soil in your hand and no matter where on Earth you squat you hold billions of bacteria and fungi, nearly all of which science has not yet described. In that scoop wriggle tens of thousands of nematodes too, the most abundant and diverse multicellular animal on the planet. They are some of the most intensely studied animals too (they were the first to have a complete genome sequencing, and some have even gone to space), yet only 35,000 species have been described out of the estimated million thought to exist. Their roles, and the roles of virtually all other soil organisms, will remain mysterious for many generations to come.

Nematodes live in every soil. Their role is crucial to soil yet we no little of who they are and what they do. // Photo: Prof. Eriwn Huebner, Biological Imaging Facility, U of M

Geographically: More than 700 soil series (“series” is the soil world’s equivalent of “species”) have been described in Manitoba, but soil scientists have surveyed – not even in great detail – only a third of the province. Detailed surveys have been done on just 1/50th of this province’s land, and mostly in the south for farming’s sake. In short, we know little of our soil.

Chemically: Soil is the bed all terrestrial life rests upon, allowing photosynthesis to occur on land instead of just in the seas. It regulates atmospheric gasses and offers various Earth systems a depot to store chemicals, for good or ill. It may also prove an invaluable place for humanity to store carbon, offsetting the effects of climate change.

Physically: Shrink yourself to the microscopic scale and enter this benevolent and yet often violent ecosystem. Slide a nanometre to the left. You moved one billionth of a metre yet now stand in a different environment, perhaps too hostile for you to live in. No other ecosystem offers such a gargantuan supply of niches for life to exploit and diversify within.

Historically: A population boom in the late Middle Ages pivoted on the ability of northern Europeans exploiting their rich, heavy clay soils, which tantalized them for generations until they invented the heavy plough. Other cultures in other times experienced the opposite, abusing their soils to their own detriment. The village of Dazhai in central China in the 1960s, the Sahel swath running through western and north central Africa in the 1970s, Easter Island in the 18th century – history shows that soil is quickly lost and slowly regained.

“The history of every nation,” Franklin Roosevelt once said, “is eventually written in the way in which it cares for its soil.”

In the article “Our Good Earth”, however, National Geographic notes that our modern and political institutions are not set up to care about soil, which is why we have degraded 19 million square kilometres of soil – an area roughly the size of North America. If we expect to support 8 billion people by 2025, we need to care more about soil.

But what is it?

Soil, dully stated, is a mixture of decomposed rock, air, and water, and the air and water create pores throughout the mixture.

“But let’s jazz up the definition a bit,” says Tenuta, Canada Research Chair in Applied Soil Ecology. “I’m a biologist, so I would say a definition of soil is a mixture of minerals, gases and liquid that has been modified by the actions of organisms. So we have this wonderful material that’s added to soil and it needs to be in soil or else we can’t call it soil, and that is organic matter: the products of living organisms.”

Feces, animal workings, the remnants of plants and animals that bacteria and fungi decompose, rework and digest – this is the crucial ingredient in turning ground stuff into “soil”. It’s these components that give soil its black colour too.

Soil is not necessarily black, however. Australia’s vast red soil and that of Prince Edward Island, is red because it’s low in organic material and high in iron, which is red.

Manitoba’s soil is relatively new, dropped from a glacier about 10,000 years ago. Or more accurately, the glacier deposited parent material, mineralogical debris that transformed into soil once organic materials occupied it. Rivers and wind create new soils in this way as well, shuttling parent material to new places for new soil series to begin.

“The other means for this, and this happens every day in Manitoba, is by the retreat of Hudson Bay,” Tenuta, says. “Hudson Bay is slowly moving and every day we gain from Nunavut a little bit of land that becomes soil. We gain about 1.5 centimeters a year.”

When the burdensome load of the glacier dissolved, Earth’s crust began its long, slow rebound upwards, and now every day along Hudson Bay new parent material emerges.

“You can walk up to it and say, ‘That’s going to be new Manitoba soil.’ It’s pretty cool,” Tenuta says.

Joseph Henry Ellis first described Manitoba’s soil. A graduate of the Manitoba Agricultural College prior to its joining with the University of Manitoba, he became in 1927 the first head of the University of Manitoba’s Soils Division (to become the department of soil science) in the department of agronomy, a position he held until 1955.

Ellis gained notoriety for mapping and classifying Manitoba soils; upon his retirement in 1955, he had surveyed 18 million acres of farmland, the Western Producer reports. This enormous project proved invaluable in helping farms rehabilitate after the 1930s drought. Ellis, though, intended his classification system to be a temporary one, yet it proved worthy and helped form the basis for soil classification throughout Canada.

Ellis’s legacy lives on in textbooks, and it was a textbook that inspired Tenuta to pursue research in soil sciences. He was studying geography and botany in university and enrolled in a soil science course. He recalls buying and reading the entire textbook before going to the class. He found his passion.

“To me, it’s incredible that soil is what allows plants to grow. And that’s before you even get into the microorganisms. Soil does so much for us in terms of its position in the environment and in all the cycles. You name the type of cycle – carbon, nitrogen, water, any type of cycle – and soil is involved, with living organisms in soil utilizing and transforming the elements and compounds, which changes things,” Tenuta says.

“If you look at the atmosphere and aquatic systems, the key to their composition is the soil – it gets rid of our toxins, it is a source of nutrients, it sustains food production and lets us build our homes. It does so much for us. Surely it isn’t dirt.”

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.