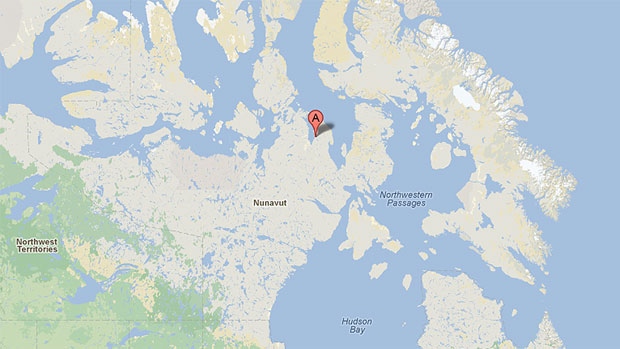

Introductory panel from the exhibition, "We Were So Far Away . . . The Inuit Experience of Residential Schools," organized and circulated by the Legacy of Hope Foundation. Nunavut landscape, 2008. Photographed by Marius Tungilik. // Image courtesy of Legacy of Hope Foundation

Northern pedagogies: U of M faculties rise to the occasion

Even before advancing Aboriginal education became a fundamental pillar of the U of M’s Strategic Planning Framework (SPF), there were many U of M faculties working to increase the cultural responsiveness of their pedagogies to issues faced by northern and Indigenous communities. Here are two stories about how faculties are working today.

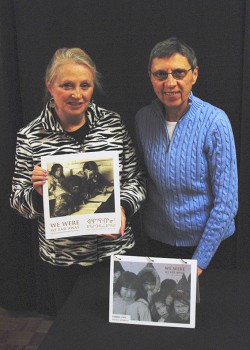

Associate professor of Nursing Elaine Mordoch with Nunavut-based community health nurse Millie Dietrich, pictured with materials from the exhibition.

Recently, the College of Nursing in the Faculty of Health Sciences hosted a Legacy of Hope exhibition about Inuit Residential School survivors, called “We Were So Far Away.” The exhibit ran from Nov. 10 to 14 with week-long events and speakers planned by associate professor Elaine Mordoch and her nursing colleagues, assistant prof Donna Martin and students Kendra Rieger, Crystal Cook and Cindy Van Eindhovens. Most recently, Mordoch has been studying how inter-generational trauma affects school performance of mature Aboriginal students. By highlighting these and related themes in her teaching, Mordoch helps to prepare the next generation of nurses to give expert mental health care.

The week of the exhibition also included a visit by Nunavut community health nurse, Millie Dietrich, who spoke on panels and in classes to nursing students about the challenges and rewards of nursing in northern communities. Her presentations touched on issues of mental health, northern nursing, cultural safety and learning to work with a community.

Kugaaruk, where she has lived since 2006, is a very traditional community that retains its language and culture — it’s part of what drew Dietrich there.

Having worked in Northern Canada for much of her career, Dietrich, like Mordoch, believes that acknowledging the social, historical and cultural determinants of and attitudes towards health and wellness is critical for nursing and health care professionals, where relationships are key.

She says that Kugaaruk, where she has lived since 2006, is a very traditional community that retains its language and culture — it’s part of what drew Dietrich there. She had previously worked in Northern Manitoba for about 15 years, and before that, in hospitals.

After about 15 years of working in Northern Manitoba, she realized that she was seeing a lot of mental health issues and and addictions and so she returned to school. After a Bachelor of Science in Nursing, she continued with post-graduate work in mental health, and then worked for a while with the Mental Health Crisis Stabilization Unit in Winnipeg. When she learned there was a need for mental health nurses in Nunavut, she decided to take a post.

For Dietrich, the wonder and beauty of the North were added motivation.

The wonder and beauty of the North were added motivation, says Dietrich. “We see animals and mammals that you don’t see down here [in the South] — and to me, that’s part of the North. Because when you see a caribou for the first time … you’re in awe. And when you see a muskox for the first time … well, that is a prehistoric animal. I saw a herd six feet away and [I thought] I can’t believe what I’m seeing, you know? And there’s narwhals and walruses and the beluga whales and the bowhead whales — you just don’t see those anywhere else but up in the Arctic. And certainly the northern lights — they’re absolutely gorgeous…. The land is so pristine. And depending where you live, sometimes you’re surrounded by mountains and sometimes it’s just plain flat tundra — but that itself has beauty. And in summertime, when … you see flowers come up in the tundra, [you wonder] ‘How does this happen?’ Those are the rewards.”

Working in an expanded role — as is the case for many nurses working in the North, due to a lack of doctors — means that her plate is full.

Comments Dietrich, “Living and working in Nunavut — learning a lot about the culture, and they embraced us — there were a lot of mental health issues, certainly with depression and substance abuses, and, as I began to realize, there was the inter-generational trauma, too. A lot of people who were coming to me for counseling was all related back to the Residential School system and how it impacted on their lives today.”

In a population of 34,000 in all of Nunavut, there were a record 45 deaths by suicide in 2013, many of those in the male population between the ages of 15 and 25. Deitrich was invited to the U of M after Mordoch heard her present a paper on suicide at the Canadian Mental Health Nursing Conference.

Presenting her findings to U of M nursing students, she stressed the impact of inter-generational trauma traced back to Residential Schools. She touched on the complex dynamics of fast-growing population, residential overcrowding and cultural trauma. Dietrich emphasized the importance of building respectful relationships and honouring Inuit cultural wisdom in nursing care.

Nunavut is a huge territory — but there’s a small population, she notes. “These people had their childhoods taken away. Having been taken away from their parents … many of them were without role models, in terms of parenting skills or even coping skills.” That, she says, has had serious consequences for the generations that followed.

Dietrich: ‘I felt that it’s important that I share the challenges that we are experiencing up in Nunavut — especially the high rates of suicide among the [young] male population…. It’s very sad.’

“I felt that it’s important that I share the challenges that we are experiencing up in Nunavut — especially the high rates of suicide among the male population between 18 and 25. It’s very sad. For most of them, the lethal means is hanging…. This year, the youngest death was 11 years old. It’s hard to get your head around it.”

For Dietrich, even the harshness is offset by the rewards. Her experience of working in the Arctic has been deeply gratifying, she says, in part because the community is warm and inclusive. “Living and working in a culture, you are very accepted by the community because they are so appreciative to have nursing help and mental health help.

“The long winters and the darkness … that is harsh. But when it starts to become lighter and lighter, and there’s joy.”

–Mariianne Mays Wiebe

***

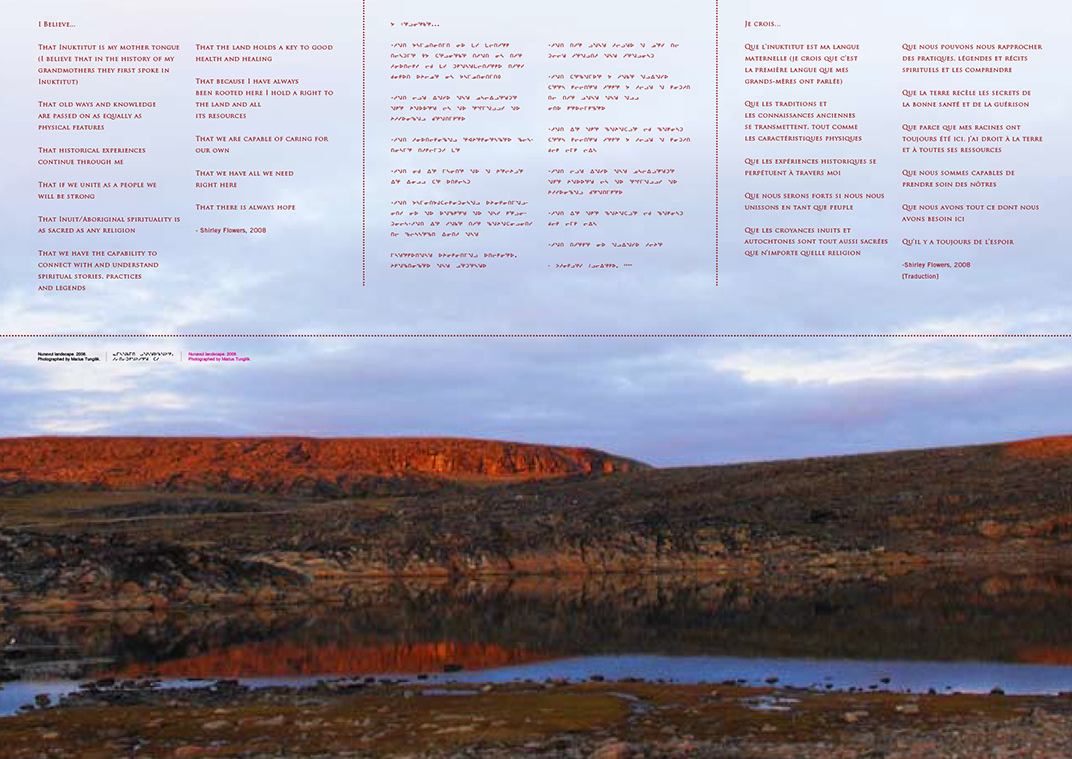

I Believe…

That Inuktitut is my mother tongue/ (I believe that in the history of my grandmothers they first spoke in Inuktitut)/ That old ways and knowledge are passed on as equally as physical features/ That historical experiences continue through me/ That if we unite as a people we will be strong/ That Inuit/Aboriginal spirituality is as sacred as any religion/ That we have the capability to connect with and understand spiritual stories, practices and legends/ That the land holds a key to good health and healing/ That because I have always been rooted here I hold a right to the land and all its resources/ That we are capable of caring for our own/ That we have all we need right here/ That there is always hope

– Shirley Flowers, 2008

The poem on the tundra banner (pictured top) for the exhibit, “We Were So Far Away . . . The Inuit Experience of Residential Schools,” organized and circulated by the Legacy of Hope Foundation:

***

Faculty of Education’s Northern Practicum

Northern Practicum students hope to gain understanding of Indigenous communities

Indigenous traditions, polar bear expeditions and unparalleled views of the aurora borealis — these are some of the unique experiences available to students who choose to do their teaching practicums in Northern Manitoba. And this year, the program has proven more popular than ever, with an increase in the number of students competing for spots.

In all, 11 Bachelor of Education students are participating in the Northern Practicum: four in Gillam with Barbara McMillan, four in Norway House with Frank Deer and three in Churchill with Richard Hechter.

That means the program, which began as a renewed partnership with the Frontier School Division in 2012-2013, has really grown in just a few short years, says Melanie Janzen, the Faculty of Education’s director of school experiences. That first year, the faculty placed four teacher candidates in Northern Manitoba.

“This year we had 16 applicants [for the 11 spots], so I was thrilled,” she says.

The program began two years ago with several goals, says Janzen: to increase the number of practicum opportunities available to teacher candidates in rural and Northern communities, to cultivate a renewed relationship with Frontier, Manitoba’s largest geographical school division, to break down stereotypes about working in the North and to raise awareness of Indigenous traditions and communities. And, last but not least, one of its goals is to provide a viable source of employment for U of M Education students.

Janzen says that those who have opted for the Northern Practicum have not only learned about Indigenous classrooms but also have been embraced by the local communities.

“Teachers have been getting hired by Frontier School Division [after they complete the practicum] which means that even Manitoba’s more remote communities are having the opportunity to hire new and vibrant teachers from within Manitoba instead of having to rely on hiring from Eastern Canada,” says Janzen.

Students often don’t consider the North when choosing practicums, says Janzen, but she adds those who have gone have not only learned about Indigenous classrooms but also have been embraced by the local communities.

“They’ve gone fishing, curling, they’re invited for dinners, they’re eating game and pickerel.

“It really breaks down stereotypes that our teacher candidates may have of Indigenous peoples and communities,” she says.

The students

Students headed out on this year’s Northern Practicum were anticipating a remarkable experience.

Sandra Eaton, in her second year, says her interest was piqued last year during her Aboriginal education course. Students took part in a variety of activities including beading workshops and spending time in a sweat lodge. Eaton sees the trip it as an adventure as she hasn’t spent a lot of time outside of Winnipeg.

“I’m excited to get to do that,” says Eaton, who is teaching Grades 7 and 8 in Gillam. She was trying not to develop preconceptions about the North before leaving, though she did get some good tips from McMillan, her adviser. During a seminar on culturally responsive curriculum prior to the practicum, McMillan told students that they might be surprised at how respectful and quiet students are in the North and that it may take them a bit longer to think about and answer questions.

Second year student Bailie Park-Payne said that she was most looking forward to teaching in Churchill because it’s a small, close-knit community.

Another second year student, Bailie Park-Payne, said before she left that she was most looking forward to teaching in Churchill because it’s a small, close-knit community. She’d like to learn as much as she can about Indigenous culture and develop a better understanding of the ways people live in the North. And the experience may set Park-Payne and her colleagues apart from other teacher candidates when it’s time to apply for jobs, she says. While in Churchill, Park-Payne is working with Hechter to develop a science curriculum that incorporates the northern lights in unique and interesting ways.

And, of course, there are the polar bears, too. She says the research centre there has its own tundra buggy so she’ll be taking her camera.

Seeing what land-based education looks like is one of the main reasons Morgan Schrader applied to the Northern Practicum. Based in Norway House under the advisement of Deer, Schrader plans to spend a fair bit of instruction time outside, connected to nature in the tradition of the community. As a Phys. Ed. and Early Years teacher candidate, she is hoping to learn about trap setting and some of the traditional sports that Frontier School Division promotes.

As well, no matter where her career takes her, “gaining that Aboriginal perspective is very much needed in any of the school divisions we are going into.”

–Allison Dunfield

Follow the Faculty of Education Blog here.