Voices of Pandemic Past

Spring 2021

Wayne Chan, a research computer analyst, makes for an unlikely historian.

This University of Manitoba alumnus and staff member, who is normally focused on data analysis at the Centre for Earth Observation Science, turned his curiosity toward the forgotten pandemic of 1918-19. During his investigations, Chan [BSc/93, BA/00] uncovered little-known stories of rural Manitobans forever changed by the Spanish Flu.

These excerpts from his recent article in the Manitoba Historical Society’s Prairie History journal bring to life a hardship and a hope to which we can all now better relate. Putting pen to paper is something everyone should consider, he insists.

“You may believe that your personal observations of life during COVID-19 are mundane,” writes Chan, “but they may be invaluable to historians years from now. The future will thank you for your efforts.”

Evelina “Eva” Adams (née Sinclair, 1898–1990) was a twenty-year-old, newly-trained nurse at Neepawa when the flu arrived. Her 1982 autobiography recalled harrowing experiences that followed // Photo by Gerald R. Brown

The pandemic was a trial by fire for medical staff who were just starting their careers. Twenty-year-old Evelina Adams was a nurse in Neepawa when the flu arrived. When the second wave hit in the spring of 1919, she was sent to the farm of Arthur Murray, whose eight children were stricken. Worst off was 14-year-old Kenneth, who had developed pneumonia. As Evelina recalled in 1982, “The boy was very ill, and in those days we did not have antibiotics to fight this condition; the doctor and I did our best but after two days and one terrible night he died.” Over 60 years later, Kenneth’s sister Norma remained grateful for the help of Evelina and the doctors who tried to save her brother: “Even at this late date we remember and we thank them with all our hearts,” she said in 1983.

Many survivors recalled their local doctor working night and day during the pandemic. Ethel Bruce’s husband, Dr. Edwin Bruce, was the physician for Swan River Valley. When Ethel was interviewed in 1978, at the age of 97, she remembered that “… he was scarcely ever at home, but went from one house to another, keeping in touch by telephone. At one time he was three days and nights without sleep, and would have to get out of the car and run up and down the road to keep awake so that he would not end up in the ditch.”

Then, as now, congregate living spaces were often the sites of outbreaks. In St. Boniface, the ranks of the Grey Nuns were decimated as they tended to the sick and ended up contracting the illness themselves. In the words of Sister Beaupré, “The most commonly used vocabulary in November has been made up of the words: sick, dying and dead…. At St. Joseph Orphanage in Winnipeg, one hundred and two orphans and all the sisters, except for three, are paying tribute to influenza. The three who are still standing are doing so only by their strength of will.”

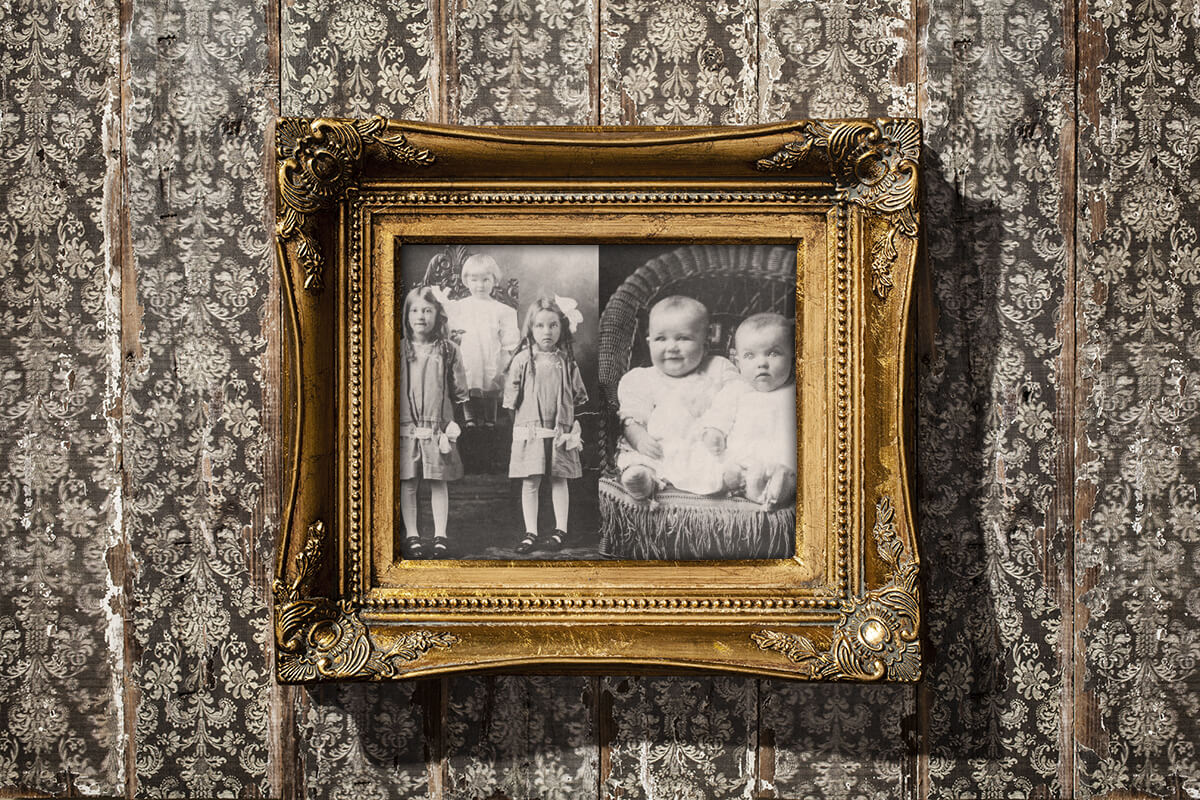

The five children of Louis and Marie Halwas, shown left to right, Donna, Laleta, Ella, and twins Wilfred and Lily, all died in the span of three days in early 1919, along with their mother. All are buried in the Freefield Cemetery // Reprinted by permission of the RM of Riding Mountain West and Gerald D. Halwas

The amount of loss within single families was sometimes staggering. In the former RM of Boulton, just west of Riding Mountain National Park, Louis Halwas lost his wife Marie and all five of his children, aged between one and 10, in the span of three awful days in early 1919. All are buried in Freefield Cemetery. These situations were unfortunately far from rare—numerous town histories mentioned families that suffered multiple losses. It is difficult to see how anyone could have overcome these devastating losses, but Louis Halwas soldiered on, remarried a year later, and began a new family. His descendants continue to live in the Riding Mountain area.

Not only did families have to deal with the loss of their loved ones, they had to act as undertakers on occasion. Michael and Anna Chorney and their eight children had emigrated from Poland to settle in the Beausejour area in 1904. Like countless other families, tragedy struck the Chorneys in 1918. As related by Josephine Naaykens (née Modrzejewski), “On November 24, 1918, the Chorneys lost two children. Roman, a young man of 22 years, died at 5 p.m. and Olga, age 18, died that same evening at 11 p.m. With so many people ill and no undertaker at the time, the pioneers had to take care of their own loved ones. Michael built the coffins with the help of the Modrzejewski family. Anna had to dress them and they both laid their children away. Their graves were dug by the family and their loved ones were lowered to their resting places. They did not cover the graves immediately because another child, Teenie, was also very ill at the time and they thought perhaps she too would die. However, her fever broke and the family went back to the graveyard and covered Roman’s and Olga’s graves.”

Indigenous communities in the north were not spared. In 1979, Felix Mahzenekezhik, a resident of Norway House, remembered that “a lot of our people died in 1918 with the flu. There were young people and old people and babies dying every week.” Nearly one-fifth of Norway House’s population was lost in a six-week period. Because the frozen ground was too hard to dig graves, the dead were wrapped in sheets and laid on rooftops to keep them away from dogs until the spring.

Simply staying warm was an issue when the entire household was ill. John McRae, who was eight or nine at the time and living in the Melita area, recalled, “In those days there was no such thing as automatically controlled heating systems in the homes and the coal and wood burning stoves and furnaces had to be replenished and ashes removed by hand whether you were sick or well, and in the case of the farm families, coal had to be hauled from town by horse drawn sleighs. When, as sometimes happened, all or most of the members of a family were sick at the same time, just keeping warm was a problem and if there was livestock to look after on a farm it served to compound the problems to be overcome.”

In an era when telephones were still not common, help could seem impossibly far away. At Oak Point, near the southeastern shore of Lake Manitoba, Julius Zacharias was sick with the flu, but dragged himself out of bed to seek help for his wife, who was in labour and also ill with the virus. “I walked to the first neighbour. I was so weak. I had not eaten in three days. It was not a mile, but I sat down many times in the snow and rest[ed]. When the neighbours saw me, they were amazed that I had come in such condition.” The neighbours accompanied Julius back to his home, where they were able to safely deliver the baby. But it left Julius’s wife in such a weakened condition that he thought there was no hope for her: “… I sat down, weary and was very sad. There were five little children and not much to eat and if my wife died there would be no money for the burial. Now I know I looked up to Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith….” Julius’s prayers were answered—his wife survived.

Modern life has often been decried for the loss of social cohesion within communities; so, it has been heartening to hear stories of neighbours coming together during the COVID-19 crisis. This was certainly true in the last pandemic. In a history of the former RM of Silver Creek, Evelyn Avery said, “… that was when the word ‘neighbourliness’ had its true meaning. When whole families were sick in bed, there was always a neighbour or neighbours who would bring homemade soup, bread, and other foods for those who were ill, and care for them, and the menfolk looked after the farm animals, then when that family recovered, they in turn did these neighbourly tasks for another family who was ill.” There were even cases where children who were orphaned by the pandemic were adopted by neighbours.

Some of the folk remedies touted a century ago seem quite odd now. Aside from the oft- recommended shot of whisky, people wore bags of camphor around their necks and some gargled with kerosene. Others wore garlands of garlic to ward off the disease. Dmytro Melnyk recalled an incident with his father, who had to mind the post office in Hodgson because the postmaster had taken ill. “He had to report to the Fisher Branch station agent as to how he was progressing. One day, father spoke to McCarthy, the CNR agent. He almost got chased out of the CNR station because he smelled of garlic, but father explained to him that, that was what was keeping him going. In about two weeks, McCarthy’s sister was sick in bed. McCarthy asked Dad to get him two pounds of garlic, and he and his sister made beads of them and wore them.”

Decorated airman Alan Arnett McLeod (1899–1918) endured the ravages of the First World War only to die of the flu within days of arriving home // Photo by Wikimedia Commons

The influenza pandemic claimed more lives than the First World War did, and some who managed to survive the front lines were cruelly taken by the disease on their return home. While flying a bombing mission over France, Stonewall’s Lt. Alan McLeod and observer Lt. Arthur Hammond were attacked by eight German fighter planes. They managed to shoot down three of them before both men were wounded and their Armstrong Whitworth biplane caught fire. The aircraft crashed, but Alan was able to drag Hammond to safety. For his actions, Alan was awarded the Victoria Cross. He returned to Stonewall a hero, only to die of the flu a little over a month later on Nov. 6, 1918. He was 19.

Remarkable stories! And great accompanying images. The frames really draw you in.

Fascinating. I’ve always been curious about the 1918-19 flu epidemic as I knew that my great-aunt’s husband and baby daughter both died within 3 months from it. It seems incomprehensible to me that people were able to survive such devastation, without modern medicine.

Brings out the humanity of the Spanish Flu so it’s not just an abstract disease. Thank you for the research and the story.

So very sad. Thank goodness for modern medicine. Many people don’t realize what our current pandemic would be like without scientific advancements.

Amazing history, sad.

My mother who was the eldest of 8 McLeods of WoodBay MB was in her,early 20s when the Spanish Flu hit Manitoba. She went from farm to farm caring for the families this pandemic struck. She never became ill herself but lost her cousin and best friend. She would tell the story to me and tear up every time. Wood Bay no longer exists but was about 6 miles south east of Pilot Mound. My dad a WW1 veteran did not become ill either. I never imagined such a pandemic would occur in my lifetime

I am very grateful for all the medical care provided today. I myself am a polio survivor and well remember being in the hospital in an iron lung as many were, the hospital was full of very sick people. I can’t thank the wonderful nurses and doctors enough for their dedication in extremely trying times. Reading this article makes one thankful for all that we have today.

Congratulations to Wayne Chan for unearthing these pandemic encounters from so long ago. May we learn from these lessons of courage, resilience and intelligence as we face new health challenges.

Many thanks to Mr. Chan for this very informative article. I knew of the Halwas family from my husband William who grew up at Inglis Manitoba. Those of us that are in our 70’s know of family members who were lost in the Spanish flu. Those, like William, who survived the Polio epidemic in the 50’s are well aware of how devastating a pandemic can be.

It is good to be reminded of the importance of community in times of crisis. It helps to get through the bad times and heal for the future. I remember hearing my great great uncle’s story at a family reunion 40 years ago. They were not forgotten. Thank you for the pictures and the article.