*UM mourns the loss of Justice Murray Sinclair, a valued member of our community, who passed away Nov. 4, 2024. He spoke with UM Today The Magazine for this story in February 2023.

Dear Sarah.

It’s how Murray Sinclair began compiling what would become his memoirs. It was the opening of a letter—the first of many—he started writing two decades ago this year, to his then-baby granddaughter after a health scare that had him questioning his longevity.

“I was feeling vulnerable and I thought, ‘Well, she’s never going to know anything about me or my family or my history, or anything about what I think.’”

Each letter continued the same way: “I want you to know about…”

His brothers were high on that list, and the laughter in their childhood home on the St. Peter’s reserve near Selkirk, Man. So was learning to fish and hunt with his grandfather, Jim, who liked to say: “You could get one day’s work out of one boy, but you couldn’t get any work out of two.”

Sinclair’s favourite photo shows him, at five, with his younger brother Henry Jr. (Buddy), smiling in their rubber boots. A closer look reveals a young Murray wearing both right feet and Buddy, both left. “We’re one person,” says Sinclair [LLB/79, LLD/02], with a smile.

Their grandmother, Catherine, and their aunts raised the four siblings following the death of their mother, Florence, from a stroke not long after Buddy was born. Alongside the twin-like boys in this treasured photo: their sister Dianne and older brother Richard. All of them were smarter than he was, says the former judge and Senator, who retired as one of Canada’s most prominent voices against racism and injustice.

Sinclair admits this decades-long journey of advocacy took a physical toll. Not long before our interview, he was waiting in a Winnipeg ER with a racing heart. His kids want him to slow down. “My daughters will tell you what an insubordinate father I am,” he says.

During six years as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Sinclair figures he sat down with roughly 5,000 Survivors of residential schools, listening in-person to each of their stories of abuse. The details were harder to absorb than he anticipated.

“Whenever they cried, we cried with them. We didn’t really appreciate just how heavy it was going to be. Winnipeg was our first major set of hearings and after that session was over and we were debriefing I can remember one of the commissioners saying, ‘My God, are they all going to be like this?’ And they all were.”

I don’t think of my life as a single incident or that there’s one incident that’s more important than another. They all came together to create who I am.

Sinclair had declined the role when first asked in 2007, having worked on an intense public inquiry a few years earlier. He led hearings into the deaths of 12 babies who were victims of a flawed cardiac surgery unit at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre in the mid-1990s. The majority of them came from vulnerable circumstances; more privileged parents could send their children out of province for better care.

“The unfairness of all of that was pretty rampant and so I was still emotionally very affected by that,” says Sinclair, who at the time made a bookmark by hand, burning the children’s names into a strip of leather as a reminder. “I couldn’t remember the order in which they died. I couldn’t remember their names. It became more and more emotionally important to me to have that handy, and to hang on to that after the inquiry was over.”

His career of telling the truth about broken systems—and who they fail—almost didn’t happen. The man tasked with being witness to the testimonies from the thousands of Indigenous people harmed in residential schools, mostly by Catholic priests, almost became a priest himself. His grandma, as a young woman, was intent on becoming a nun but when she decided to leave the convent she could only do so in exchange for a pledge to foster this commitment in a child. Sinclair grew up understanding he would fulfill on that promise (she didn’t let him date until his 20s, in preparation). When he finally pushed back she conceded, but had him vow he would do something good with his life.

She and her grown daughters had already planted the seed for education. When Sinclair asked for a bicycle for his twelfth birthday, an aunt bought him a set of encyclopedias—she’d then quiz him once a month on the content. That was his gamechanger, he says. With $1,000 his grandma saved, he’d go on to pursue university, but the UM law grad wasn’t always convinced he wanted to be part of a system that felt so discriminatory.

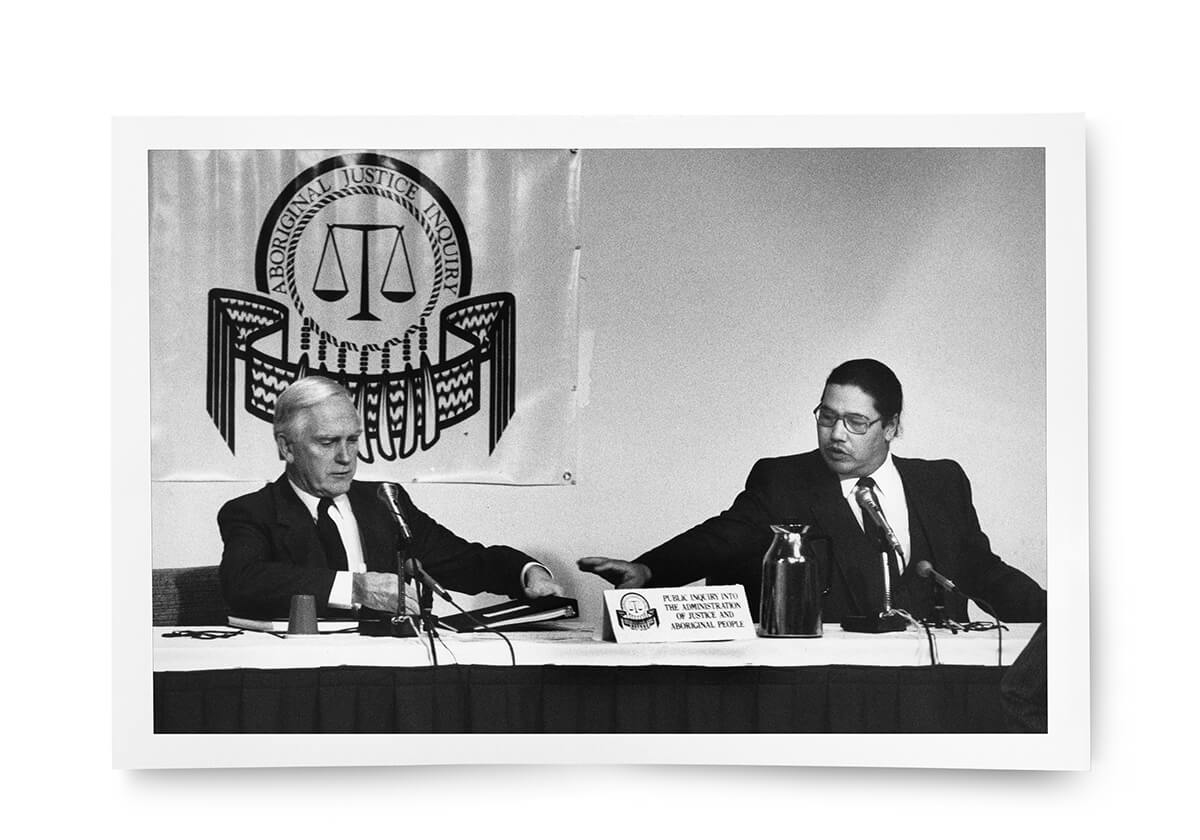

As an Anishinaabe lawyer, who sometimes got mistaken for the accused, Sinclair pushed through and would become Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge. He led the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry into the role racism played in the investigations of murdered Cree teenager Helen Betty Osborne and the police shooting of Indigenous leader J.J. Harper. Today he says the majority of the 296 recommendations in that 1991 report have gone unfulfilled—and he’s not surprised. But still, he says, it moved the needle.

“I pressed hard for us to have…an impact on the level of awareness among non-Indigenous people towards the fact that the justice system is not perfect, and that the justice system can and had been used to eliminate the rights of Indigenous people and to negatively affect them. And the data supported everything that we said,” says Sinclair.

Photo by Dave Johnson/Winnipeg Free Press

For all his inquiry on behalf of others, he’s found it too painful to probe an unresolved crime in his own family—the killing of his eldest brother, what may be his most cutting loss. Richard joined the Canadian Navy and would lose his life at 19, not in combat but at the hands of fellow soldiers on a train returning to their docked ship in Halifax. Richard was like a dad to his siblings as their father, Henry—who was dealing with the trauma of a severe injury from the Second World War, and the sudden death of his young wife—had left the family.

“The Navy guys were all attacked by Army guys and a number of them were badly hurt. My brother was beaten up and was thrown off the train and they didn’t find his body until the next day,” recalls Sinclair. “Originally, they charged three Army guys with his murder and then for some reason, that was never revealed to us, they dropped the charges against them. I’ve always looked at it as murder.”

Sinclair was 14 at the time and has no memory of the year that followed.

“He was the one who took care of us, kept us from being bullied at school. He would take us with him into town or wherever he was going to, you know, have a coke somewhere. He would take us along because he was that kind of a brother. He was the guy that I loved dearly…. In fact, I went into therapy for a while to figure out why I have no memory of that year after he was hurt, and it’s because I was so overwhelmed with grief.”

It wasn’t until Sinclair’s involvement with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that he learned his father was among those sexually abused in Residential School. He heard from his uncle how his dad, at age 10, was able to alert his grandma since she lived nearby. She managed to take back her kids and move away.

It would be understandable if Sinclair let negativity take over, but he describes himself as someone who does the opposite. “I don’t sit around weeping, feeling sad and feeling angry. People will tell you that I’m a very happy-go-lucky guy with a really strong sense of humour, and I use that to lighten conversations to help people transition from a particular mood that they’re feeling, to help people in their own path.”

When his niece called in tears after a breakup, declaring she “hated love!” Sinclair wrote her a poem to make her feel better. When he called one of his five grandchildren, and heard how she had just learned to sing the alphabet, he countered by freestyling a comical song of his own. He’s known in his family for his bad dad jokes, and telling long stories with ridiculous endings.

Sinclair starts each day with a prayer as he sings and plays a drum. His huskies—one of them named Stevie (he’s a Fleetwood Mac fan)—will join in by howling, as the breed is known to do, he points out. Sinclair finds direction in his spirit name, Mazina Giizhik, which means “the one who speaks of pictures in the sky.” As the story goes, Mazina searches for answers to help his people and, instead of listening to voices, looks up for messages from the Creator. “I watch birds. I watch little animals in the trees,” says Sinclair. “I watch the trees themselves and how they move.”

At 72, his insights continue to be sought for some of the country’s toughest conversations, most recently: how to move forward with the discovery of unmarked graves of children who didn’t survive residential schools. Sinclair says while some Indigenous families would prefer the remains of their loved ones be returned home, given the logistics and trauma of identifying those lost, when no coffins were used, and some graves contain more than one child, it may be best in some cases to instead protect the grounds.

I would never change anything because then I wouldn’t be who I am and I like who I am.

“I’m more inclined if it’s in an area where we can safely say that we know that this child is buried here, that to the extent possible we do not disturb that, but we do commemorate it in some way and protect it from future impact,” he says.

At the permanent home for the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, to be built on UM’s Fort Garry campus, Sinclair would like to see a re-creation of the physical space of a Residential School, similar to the immersive visitor experiences he’s found effective in archival buildings and museums elsewhere in North America.

He predicts Reconciliation, which he likens to redirecting a massive ship, is still two generations away. While non-Indigenous people participate in Orange Shirt Day and other ally acts, he reminds us that Indigenous people seek more than kindness and support; they seek rights to land and to self-governance negotiated in treaties long ignored in history books.

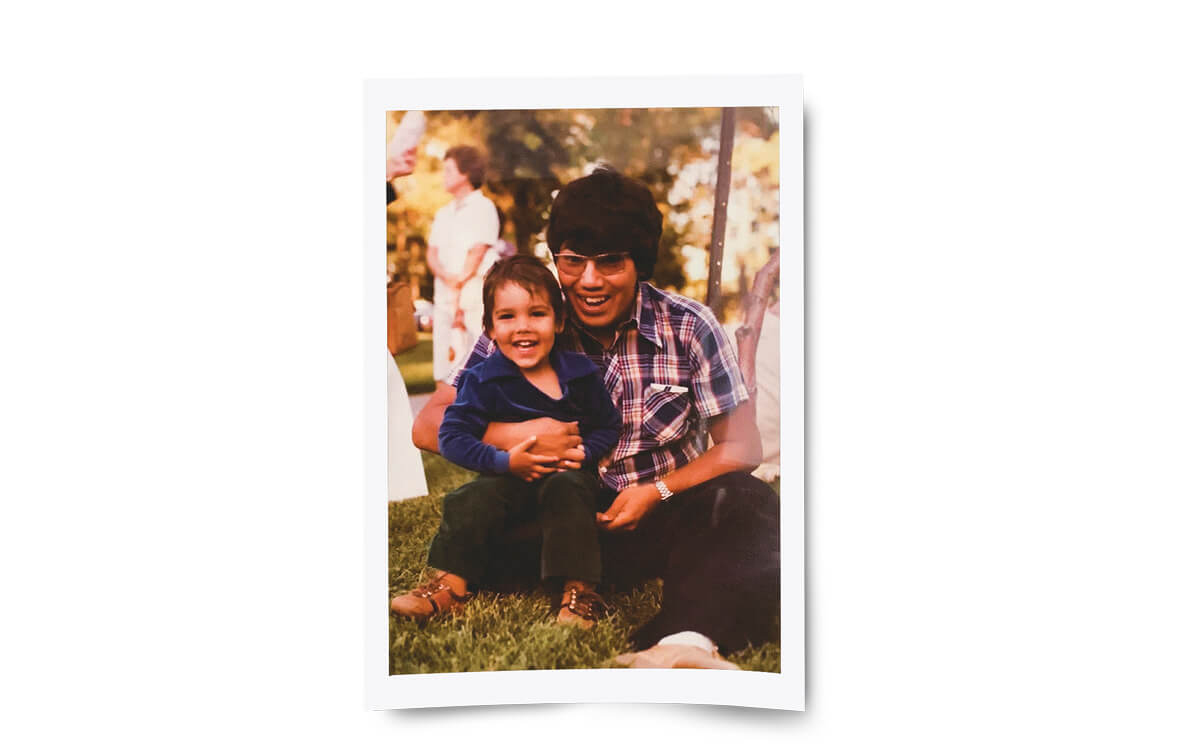

Murray and his son Niigaanwewidam, who today is an associate professor in Indigenous studies at UM // Photo supplied

When the Commission published their final report in 2015, with its 94 calls to action, Sinclair declared, “Education got us into this mess and education will get us out of it.” He still believes education is the most important step towards change—to reverse what non-Indigenous children were taught.

“We have to…recognize that our public school system was a system that taught white supremacy principles, founded on white supremacy: that white people were better than Indigenous people, than Black people,” says Sinclair. “The key to Reconciliation is to recognize that we created this through an education system that was totally wrong, but we can fix it and we can only fix it if we start to educate our children better.”

In addition to Sinclair’s three biological kids are two daughters he and wife Katherine adopted in adulthood, not through Vital Statistics but through ceremony. Each were struggling and searching for something when he met them in the community. One had lost her mother, didn’t have a relationship with her father, and sought grandparents for her children. The other was being raised by her grandparents but lost them both in a car accident, and was living on the streets. She has since gone on to Harvard University.

“They didn’t know what they were looking for. So, we helped them,” Sinclair says, from his home in St. Andrews, Man.

Today he brings his mentorship to young Indigenous lawyers at the Winnipeg firm Cochrane Saxberg and, last fall, he joined the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation and UM as a special advisor and Elder-in-residence. When he thinks about his memoirs, tentatively titled Who We Are, he thinks about questions he first heard when he was studying philosophy at UM: Where do I come from? Where am I going? Why am I here? Who am I?

But ultimately, he hopes future generations will look at his life’s work and grasp an important takeaway.

“That I cared.”

Awesome autobio. People will never understand what residential school did to our Nation.

Thank you Sir, for the important work you and your committee have done. The TRC, is a north-star, that can guide us all to better days ahead. Education is the key to unlock the chains of oppression. I have worked as a counselor with survivors and have heard many stories, which, encourages me to continue my work as an authentic ally! Mussi Cho!

Touching and powerful sharing of how and why a great human being is fulfilling his life’s purpose. May it inspire others to do likewise in the service of the global human family and future generations and for the survival and flourishing of the human race and all our relations. Thank you!

David G Newman

I have known about Murray Sinclair since the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. I was 13. I was Native. Then I heard about his as a judge. Then I heard about him with the babies in heart surgery. Then I heard about him with Truth and Reconciliation.

Murray, Senator, Sir, Your Honour, grandfather, thank you for what you have given us as Indigenous youth in Manitoba. Hope, joy, thought.

We can, we do, we are survivors.

Marsee,a Métis – Anisinaabe sister.

Thank you Respected Leader Murray Sinclair. Its your voice and your discussions with us and your commitment to our peoples that have transferred much knowledge and kindness to our journey. From the my heart and from my development that you have attributed, I give and offer my thanks.

Thank you Respected Leader Murray Sinclair. Its your voice and your discussions with us and your commitment to our peoples that have transferred much knowledge and kindness to our journey. From my heart I am very joyfully appreciative, and from my development that you have attributed, I give and offer my thanks.

Thank you for all your work!

Thank you Murray Sinclair for all you have done to educate and spoken the Truth on the Residential School & the trauma we the Residential school children experienced attending those institutions. I look to you as my Role model to continue getting a education to teach the next generation for positive change .. Thank you for being You .

Thank you for all you do Murray Sinclair on a daily basis and for all that you have done leading us to this point in our lives!You are a true leader and my role model.

We have spoken heart-to-heart about growing up Indigenous and about our Grandmothers. You made me feel so good about myself and how you want to do the things I have done in my life, I felt so honored. I was the one who was blessed with your presents,that day we met by chance at Neechi Foods restaurant.

You have a heart of gold and the mind to match!

I do the work that I do because people like you have led the way!

Marsi

The Honorable Murray Sinclair is the multigenerational voice of those who do not have a voice. He is through his candid and sacred work the light that gives hope…

As I was reading this article I was reminded of a poster I had seen that referred to the ‘Joy of Resilience’.

This wonderful man has combined a passion for justice with kindness and humility. His life seems to have a blend of both joy and resilience.

That you for modelling actions worth committing to.

Thank You Murray Sinclair for a Beautiful Heart, of courage & Courage to speak the Truth for all who didn’t have a voice for their suffering!!

I love listening to The Honourable Justice speak. I love his talk about the doubts he had about whether he could be a good lawyer: He was told, “be a good man, etc., and you will be a good lawyer”.

Murray…I guess I remember you most in my work life as the truth speaker; then the wood carver who always took it upon yourself to make others laugh at themselves, even if you didn’t agree with the teacher’s direction. Our paths have not crossed in many years, but know that I will always consider you the friend who made me look at things differently. Keep well and continue to provide our society with your guiding light, and your wisdom.

I am deeply moved and inspired by the

work and wisdom of the Honourable

Dr. Murray Sinclair.

Thank you for making this article available

to us.

May we continue to learn from his vast

Wealth of insight gracious, forgiving Spirit.

Ever since I was young , I have took an interest in you Murray ! You are an amazing human and thank Creator for you and everything you’ve contributed to Our ppl

Megwetch

Myrna Assiniboine

I want to thank the creator for you Dr Sinclair.

Thanks so much for helping all of our people.

Mazina Giizhik (the One Who Speaks of Pictures in the Sky) will be greatly honored in the afterlife as his spirit will live on long after he is gone. The memories he left as Chair of the TRC will be a footnote in the history books due to his awesome influence that he left us with. The power an’ prestige of one man who left his mark is still being felt all across the board.

Sending warm Condolences to his family, children and friends this November, 2024.

I worked in native education for twenty years. I heard many stories of the mistreatment that had gone on in residential schools. After a time it felt as if I carried a pain body with me, that I knew this terrible truth that was not being spoken about. When the truth and reconcilliation commission happened and the stories were told it was like I was unburdened and I felt the pain body and sadness had lifted. My father who was in residential school in peace River had died in 1980 at 80 years old. He did not get to share with the others but would have been happy to know the stories were being told. I knew it would be a great burden on Justice Sinclair to hear so many stories, but only someone with a pure heart would be strong enough.

Thank you Justice Sinclair.