It was the same answer every time. And it was crushing.

Zahra Moussavi [PhD/97], a University of Manitoba researcher leading a study into a potential new treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, would ask Bridgit, a participant, how old she was.

Bridgit would respond: “I’m in my 20s.”

Do you have children? “No, but maybe one day.”

At 82, Bridgit had four children and three grandchildren—and a husband desperate for her to remember.

She had enrolled in Moussavi’s study of an experimental brain treatment for its potential to slow the disease’s progression, or perhaps even reverse it. Moussavi is a biomedical engineer; she applies engineering skills and technologies to solve health-related problems. Up until then this type of electrical pulsing to trigger the brain, called rTMS or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, had been used for other conditions like depression and Parkinson’s disease but it was the first time it was being applied to dementia in Canada.

On day seven: a breakthrough, when a frustrated Bridgit said she wanted to stop. She’d had enough. While the procedure isn’t painful it can be uncomfortable. Patients wear a head piece mapping the brain while a hand-held coil delivers 25 bursts to a specific spot—it feels like someone poking at your head with their finger. Bridgit’s husband tried coaxing her to continue, reminding her why she wanted to do this: so she could remember the kids.

“Then she said, ‘But I do remember my children,’” recalls Moussavi, who promptly followed up by asking if she could tell her their names.

“She said, ‘Of course. They are Susan, Sam and Donna.”

Bridgit had named two of her children and one of her grandchildren. Although imperfect, her recollection was a big moment—the win the family was after—albeit fleeting.

“By the next day,” Moussavi says, “she was back to her normal age: 20.”

It was the kind of joyful recall Moussavi had hoped to achieve with her own mother, Soroor. She says her mom, leading up to her death in 2013, no longer recognized her.

“I didn’t expect a miracle,” the researcher says. “I just wanted to see my mom for even 10 minutes the way she used to be.”

I didn’t expect a miracle. I just wanted to see my mom for even 10 minutes the way she used to be.

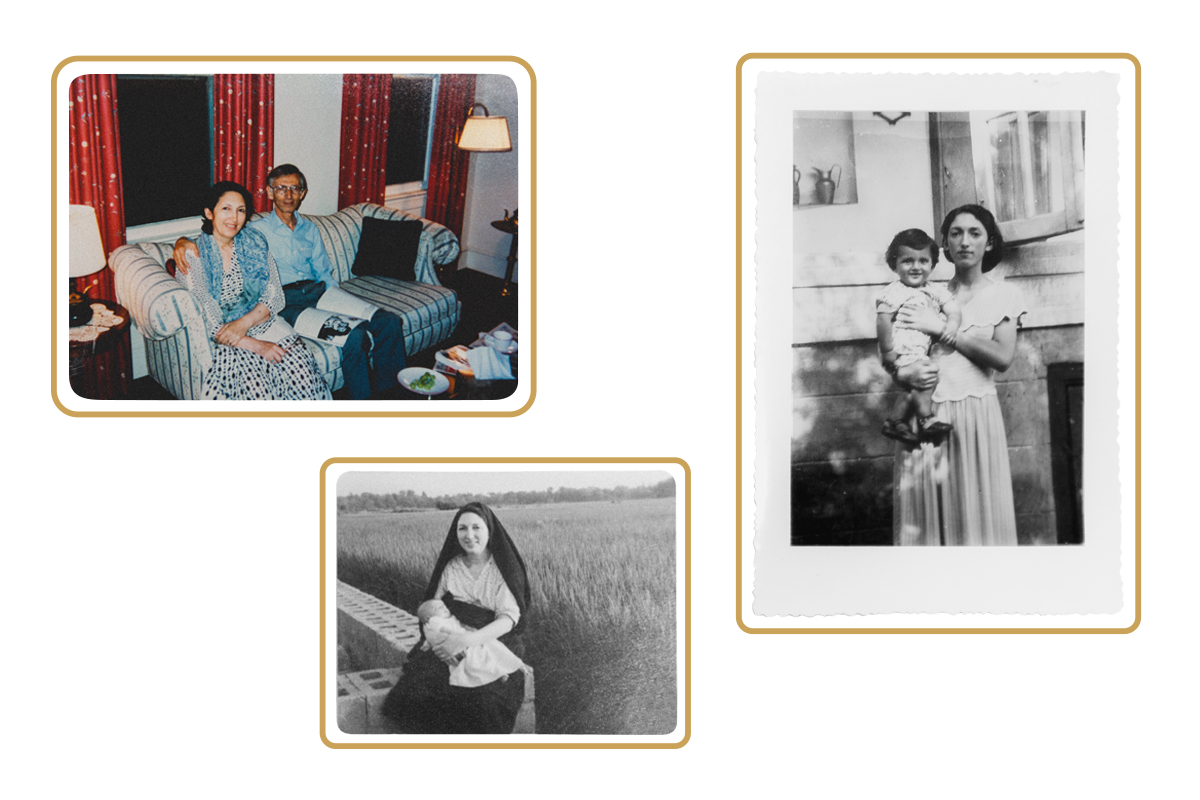

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: Zahra Moussavi’s parents; her mother, holding her brother; and holding her son

Can we really hit the rewind button on Alzheimer’s disease? Moussavi says yes. After years of research in what she calls an underfunded field of study, her findings offer hope and also sound the alarm on the importance of beginning treatment to activate those brains cells not yet destroyed by disease before symptoms progress beyond repair.

With an aging population, the number of Canadians living with dementia is expected to nearly double by 2031. The key to mitigating the effects of one of the country’s fastest surging diseases is catching it early, insists Moussavi, who is the director of the Biomedical Engineering Program in UM’s Faculty of Engineering.

Back in 2011, Bridgit was the very first patient in her pilot study. Bridgit’s memory retrieval may have been short-lived but its small success was what pushed Moussavi to explore deeper—and those first results across participants were promising. For as long as they were receiving treatment her patients didn’t decline, and some improved.

But the sample size was a mere 10 people and there was no control group, so Moussavi couldn’t yet say if their progress was from the stimulation that comes with simply getting out and routinely interacting with her friendly staff, or if it was spurred by the rTMS.

Nevertheless, a spark ignited so it was deeply disappointing when funding dried up after three years. Moussavi would spend nearly as long trying to secure further resources to launch what became, in 2016, the largest clinical trial of its kind in North America. This study, in collaboration with McGill and Monash Universities, continues today and will more fully speak to the benefits of rTMS treatment beyond the placebo effect for participants in the early and moderate stages of the disease. Psychiatrists, clinical psychologists and neurologists also make up this collaborative effort.

For those for whom the treatment is working Moussavi provides maintenance sessions, mostly funded by private donors. But not everyone responds. For those who don’t, she found an alternative in transcranial alternating current stimulation, or TACS. This technique, done every four months, attaches electrodes on the left frontal cortex and uses a current to boost excitability, paired with cognitive exercises. Two years into the study this treatment is also revealing a new way to turn back time or, at the very least, freeze it.

“I have seen significant improvement after the treatment. More than 90 per cent of participants improved significantly and those who did not improve did not decline,” Moussavi says. “The TACS is really doing something—it’s boosting the results of the cognitive exercises.”

While her latest investigations are more substantial in scope and approach than that early pilot study, the delay in getting here had ramifications. People were lost along the way, says Moussavi, who is forever advocating to treat Alzheimer’s patients soon after onset. (She once made an exception, for compassionate reasons, and enrolled a man in her study who had been diagnosed at a particularly young age—52. He was already unable to say more than a simple sentence; the treatment proved unsuccessful.)

“It was very sad,” says Moussavi. “It’s very frustrating because I have seen that we can help as long as the patient is at the early stage. These patients are on a slippery road downhill. If you lose the opportunity—that window of the first five or seven years—you have lost the opportunity.”

A more recent setback came when COVID-19 restrictions shut down Moussavi’s lab. Given she’s an engineer and not a physician, her treatments were deemed non-essential. “Three of our enrolled patients whom we did the treatment on, they declined so rapidly that they ended up in the nursing home during the pandemic. And one of them—one of our patients who was responsive to the treatment—he committed suicide,” she says. “It’s extremely frustrating. Because we can help.”

Moussavi knew something was wrong with her mom, even when doctors insisted she was fine.

“I noticed Mom was getting overly anxious when it was dark when we were driving, or when I was driving to a place and I took a scenic route for her to enjoy. She seemed to be becoming more and more anxious because it was a route she didn’t know.”

Moussavi explains how egocentric spatial orientation declines with age but it’s much more pronounced at the onset of Alzheimer’s. “That was one of the main red flags for me.”

She also noticed her mom, who married at 15, and after four children went back to school and graduated at age 46 with a 3.8 GPA, was not as articulate as she once was. Her vocabulary had decreased.

“She used to be a very sophisticated lady—very smart. And she used to have a lot of comments on political issues. She was well educated, well read.”

Moussavi took her mother to a neurologist, who did a MoCA assessment—a common test for dementia—which she passed with no problem two years in a row. “MoCA is not helpful at the onset of Alzheimer’s, especially among those who are well educated. They can disguise their symptoms. My mom aced it. She got 30 out of 30.”

It wasn’t until seven years past onset that anyone believed her mom had Alzheimer’s and physicians could diagnose it based on plaque on her brain using MRI. Moussavi would go on to develop her own test to access people’s spatial abilities, delivered using virtual reality, and those who failed—those she was able to track down four years later—did in fact develop dementia.

With gaps in current diagnosis tools, people are often not diagnosed until they are five to seven years past the onset. By that point, they may no longer be able to read or write. Moussavi says one man from her study who underwent rTMS for two weeks could once again write a coherent paragraph.

“He was so excited,” she says. “The paragraph was about a memory—a memory of his vacation.”

John and Nerina Robson in Turkey, during a stop on a 2018 cruise

The birth of his son. The day he and his wife brought their adopted daughter home. The moment they met their baby grandson. That walk in Venice together, when the beautiful voice of the gondolier nearly brought them to tears.

“O sole mio,” sings John Robson [BA/62, BSW/65, MSW/66].

These are the memories he holds on to most tightly. The retired social worker became a participant in Moussavi’s rTMS study seven years ago—a few years before he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

He had noticed changes to his short-term memory; he would forget he had done something or that he needed to do something. He also felt like his astute sense of direction was fading.

These days he loves going to see a movie with his grandson, now 14 years old. The movies have gotten more grown up over the years—John used to fall asleep watching all the kid-friendly fare, jokes his wife, Nerina.

“They were not that entertaining,” says John, “but it’s a joy.”

“John’s attitude has always been very positive,” says Nerina. “Right from the beginning, I said to him, ‘We’re going to do whatever we can to delay and have a good life.’ And we’ve done that. I keep telling him that one warning sign that I’ll see as tragic is when he forgets my name. And he says, ‘That’s not going to happen.’”

“No, it’s not,” John affirms.

Every four months John attends daily treatments with Moussavi’s team. Nerina says she believes it’s slowing his symptoms.

“The wife of one man who was there said to me, ‘This is a huge commitment to come here every day. It might not do any good.’ And my response is ‘And it might. And isn’t it better to do something than not to do anything?’ And, consequently, his decline has been very slow. It’s there, but it’s slow.”

Nerina says people diagnosed with dementia are quickly forgotten.

“Too many people want to put people in storage and I really believe we need more stimulation and progress and therapies that are attempted, like what Zahra is doing. I don’t think our provincial government is doing enough or anybody is doing enough to support the research. This is a huge issue for our citizens in Canada. Nobody is talking about it as the real epidemic that it is.”

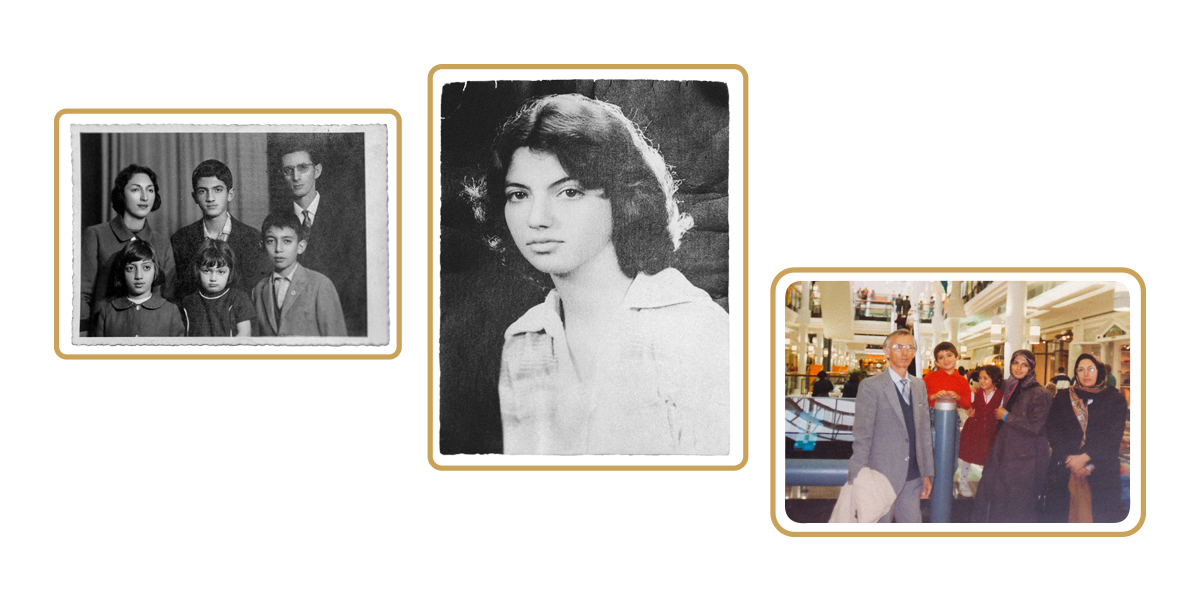

LEFT TO RIGHT: Zahra Moussavi as a child (centre) with her parents and siblings; as a teen; and as a young mother with her children and parents

How the brain works has long fascinated Moussavi, whose early life in Iran was a mix of happiness and hardship. She grew up near the Caspian Sea, feeling free as she lay in the lush, green backyard among the chickens, snails, worms and flowers.

“In the most stressful times of my life, I speak to those childhood memories. It’s my zone. I go back and feel that and smell it and it gives me a strength. It makes me feel young,” she says.

In her 20s, she would endure eight years of war in southern Iran. With universities closed, she headed to hospitals to volunteer, helping any way she could, often injecting pain medicine into those injured.

She recalls walking down the street on a sunny spring day in 1981, in the small city of Dezful, when she witnessed the gruesome death of a teenage boy. A missile landed and a piece of metal debris struck him as he rode his bike; the injury left him decapitated. His lower body continued to pedal for some time before collapsing to the ground. Beyond the horror of this tragedy, Moussavi says witnessing the marvel of the spinal cord and its ability to continue to give signals stayed with her.

“I was just seeing it in slow motion,” she says. “It was the war—these war scenes—that made me interested in the human body.”

It was the war—these war scenes—that made me interested in the human body.

How our organs communicate is complex, as is how we store memory.

In a brain with Alzheimer’s, there is excessive tau and beta amyloid proteins, which destroy the communication channels between neurons. The pulses of the rTMS treatment try to counter that by stimulating the neurons to communicate with one another again.

“Millions of neurons are being activated simultaneously in order for us to even lift a finger or say a word,” says Moussavi. “When you activate the neuron more and more, repeatedly, the brain may even create new synapses—that is called brain plasticity. And that’s the hope of rTMS. That we may awake brain plasticity.”

By its very nature, Alzheimer’s forces those afflicted to live in the moment. Could there be something freeing about not being bogged down by should-haves or past traumas? If only that were the case, Moussavi says.

“Our past memories are part of our identification—it informs who we are. If we lose those memories that have formed us we will feel lost at sea. People who can’t remember usually feel like they’re lost in time and space. And it’s such a frightening feeling because they cannot make sense of things—they see things are happening and they cannot make sense of it.”

Photo by Thomas Fricke

Moussavi’s dream is to open a first-of-its-kind centre in Manitoba for the early diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. It would be home to new diagnostic technologies, including the latest she’s developing in her lab. Electrovestibulography measures the vestibular system’s response while functional near-infrared spectroscopy measures the brain’s blood flow—these could help to better predict which treatment is best suited for a particular patient.

“Then perhaps we can optimize a strategy, not go by trial and error,” she says.

This research hub would also promote aging with a healthy brain, encouraging stimulating in-person activities like salsa dancing, as well as virtual reality opportunities at the push of a button. “It could be virtual gardening; they could plant seeds and harvest.”

The key to maintaining brain health is to not only stimulate the mind as much as possible but do so in different ways to generate new neurons and synapses between the neurons, she says, noting this could mean something as simple as switching from doing crossword puzzles to sudoku. So-called “super-agers” are those with greater numbers of synapses in their cognitive reserve. After retirement, Moussavi plans on flexing her cerebral muscle by going from professor to student and enrolling in a first-year university math course.

There are 52 genes involved with Alzheimer’s disease but only two of those genes are guaranteed predictors you’ll develop it, she says. And if you have those two genes they are always linked with early-onset. At 61, Moussavi says she avoided that fate but she could still develop the disease later in life.

“I do worry about myself. Part of this centre is for myself, too,” she says. “If I get Alzheimer’s then I will be a subject.”

A very interesting and informative article, it brings hope.

(Lonnie’s Dad)

Love the passion and understanding of how dementia feels by the researcher…here’s hoping this type of research starts to command the health funding it needs to provide life cycle health care.

Very interesting. I have a 52 year old son diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s in Regina, Sk. There appears so little is known. Need more research and government help.

My sister is 71 with ALZHEIMER. In 18 months she has declined from stage 1 to stage 6 (7 stages ?)I am her soul caregiver it is so hard and sad to see the rapid decline. It is too late for my sister, but hopefully there will be help for people with this terrible disease

Very interesting ….. My husband is 79 and was diagnosed with early onset 4 years ago. there was an MoCA assessment done and he scored 27 out of 30. Now he is scoring 19.

I was wondering if a combination of rTMS and CBD or canabis would be of benefit. The Israelis seem to be studying the effects of CBD and canabis with a bit of success. Maybe a joint investigation would shed more light on dementia.

Hi Lorraine

I will be happy to assess your husband and see for which treatment program he is eligible in case if you live in Winnipeg. Let me know.

I think CBD helps with psychotic aspect of the Alzheimer’s rather than improving any cognitive function but I’m not an expert in it.

Dear Mary Lou

if it is possible to have your son in Winnipeg for a month, I would be happy to assess him and see which treatment programs that we have would be good for him. let me know.

thanks Bob! by the way, we have started a new round of tACS and Cognitive exercises! take care

Zahra Moussavi, I wish you well in exploring/researching much needed answers.

In response to the heart tug, I will share briefly how through my own experience more than 10 minutes of quality interaction, rather repeatedly were still possible.

First by way of pertinent background, 6 months before my mother’s death in early 2014, she was diagnosed as having stage 7 of 7 dementia. However two of the best home care workers and I thought the doctor got it wrong as with our observant eyes we noticed she was still quite responsive even though for her last two years she was deemed palliative and did not make recognition with any of her other children or past friends that came by.

These years later, I’m still compiling answers to much frustrating puzzlement experienced at the time. As a new evolving definitive statement I believe Katie Chalmers-Brooks’ article expressed a very key understanding with “By its very nature, Alzheimer’s forces those afflicted to live in the moment. ”

In short, that statement puts the telling finger on how and why, even until two days before her death, we continued to have meaningful interactive contact with her.

I’ll detail but two or three events.

Until her death, with about a dozen different homecare aids over a two week schedule, I could see she responded to each aid differently. Engaging with most but unique to how they dealt with her, or guarded with the one who did not feed her safely without having to choke on her food.

Or about two weeks before her death as per our usual, mom and I were having supper with mom receiving total feeding assistance from an aid when a previous homecare worker attended for the two person job of putting her to bed. The two workers had never met before and a very jovial encounter with much laughter took place when at some point the previous worker went around my mother’s wheel chair and facing her with a big smile still on her face asked if she remembered her. I thought how stupid could she be, but in such an inclusive friendly environment to my great surprise my mother nodded. And this to an extent she had not done in years. And remember no responses to other family members for the last two years.

Then two day before her death, together with an aid, I was assisting mom but very unsure if I might be hurting her. Normally throughout the day she had her eyes closed but here within my moment of hesitation I noticed she was looking squarely at me and I asker her if I was hurting her. She shook her head!

To repeat, we did not tweak onto it at the time, but in retrospect when in a trusted INCLUSIVE safe environment that squarely involved her as well, then quite often when all that was needed was a tiny move or gesture, these words ring soundly true: “By its very nature, Alzheimer’s forces those afflicted to live in the moment. ” And when those around her were with her in that moment, the stage was set for meaningful interaction.

Should you be interested in much more that involved much more complex settings I will in reply provide my phone number.