He was about 30 feet from CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s desk when something sparked.

Vincent Cheung [BSc(CompE)/03], a member of Facebook’s Artificial Intelligence-New Experiences team, shorted a circuit while working on a prototype intended to transform how we video chat.

“That’s why you shouldn’t let software engineers touch hardware,” Cheung jokes.

There’s still a burn mark on his desk at the Silicon Valley headquarters. It’s a story the 40-year-old father of two shared on his personal Facebook page in a moment of appreciative awe as he watched his daughter Kylie, at two-years-old, call her grandparents who live a country away. The toddler did so on her own volition, using the video chat technology her dad helped bring to life. When Cheung was a kid growing up in Winnipeg, pushing a button to instantly connect with his grandparents in Hong Kong was unfathomable.

“It was really amazing today when she was rude to my parents and started walking away without saying ‘Bye’ and then later, after we talked about it, she decided to call them back by herself to apologize and ask if they could still be friends,” Cheung posted. “When I started the project five years ago, I thought that it would be useful but didn’t really grasp what we achieved until now. We literally built the future.”

His prototype launched in 2018 as Portal, Facebook’s first foray into hardware, often marketed for the ease in which little kids and grandparents can navigate its operating system, as well as its smart camera which zooms in and out to continuously frame the shot, leaving you free to walk and talk. Suddenly, everyone’s in the same room going about life without having to fiddle with their phone.

When Portal first hit stores, Cheung took a photo of Kylie at Best Buy, sat on a display next to the device. “When your firstborn meets your firstborn,” he posted on Facebook.

He can’t reveal how many of these table-top units have been sold worldwide but reports suggest sales jumped at least tenfold during the pandemic.

We don’t even realize that we live in the future now.... We don’t realize that all these relatively small changes over the past 25 years have now accumulated to the point where we literally have technology that we saw on The Jetsons growing up.

Zuckerberg himself chimed in on Cheung’s post: “It’s pretty amazing. I remember your first prototype and that original innovation makes the whole thing possible.”

It was early 2016 when Cheung—who, as an inquisitive young boy spent Saturdays in his parent’s downtown computer store, MicroAge—first starting exploring what’s possible. Long before COVID-19, the race was on to be first in this relatively new world of video chat. Amazon’s Echo smart speaker was gaining traction and there were rumours Google and Apple were also set to break through as well.

“There was some concern within leadership at Facebook…‘Is this the next computing platform? Is this something that we need to invest in?’ So I was asked to take a look at this space, figure out what can we do here,” says Cheung via Portal, while working from a makeshift office in the guest bedroom of his California home.

Another challenge the team faced: They knew there was some mistrust of Facebook, so how would people react to the company wanting to put an actual device inside their homes? And what would that device even look like?

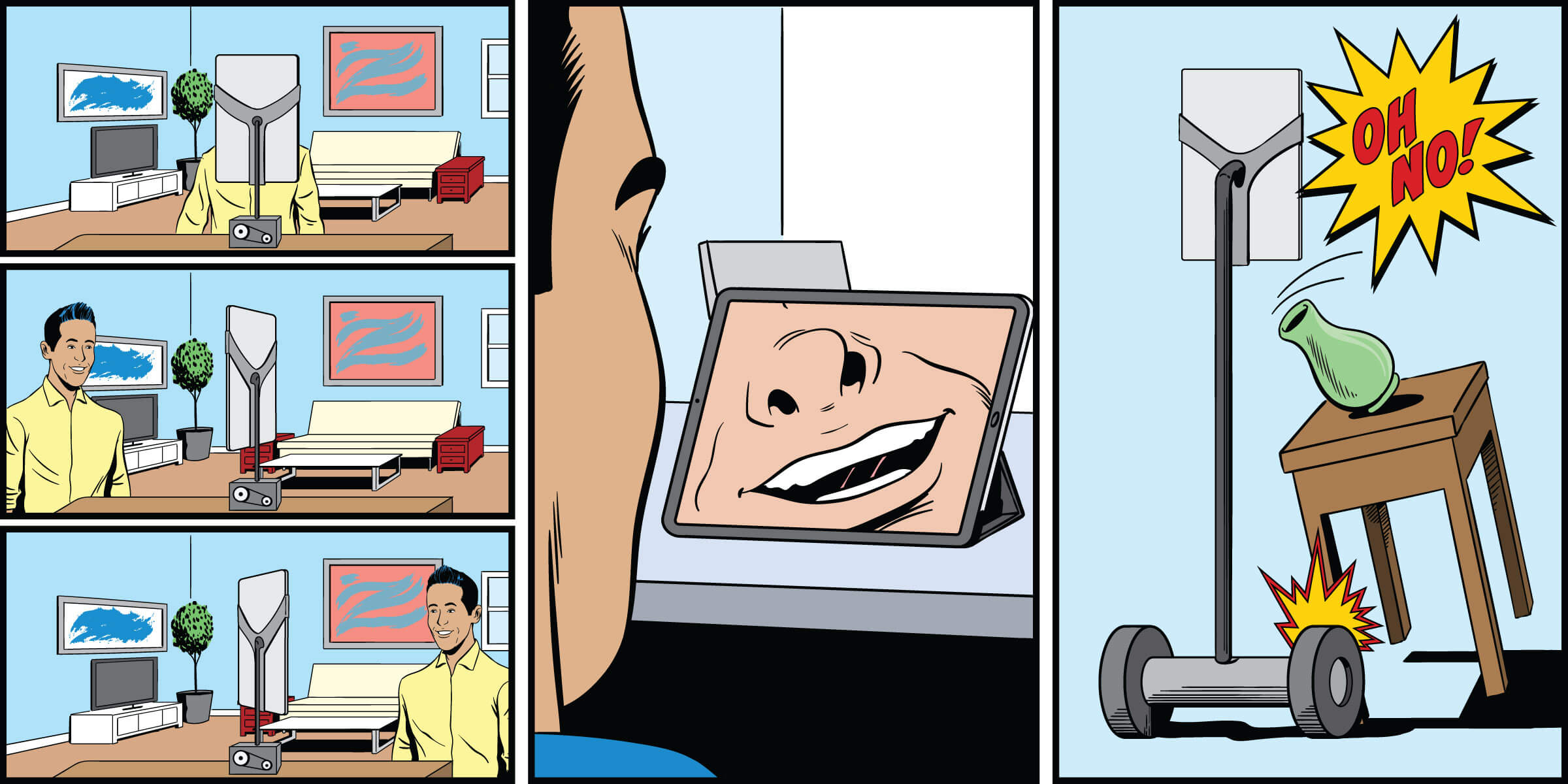

Cheung started playing around with face tracking. His first attempt was a tablet connected to a motor that would rotate as he walked around the room. He knew he wanted to build something that made video chat more comfortable, that wouldn’t crop out heads and that freed you from being preoccupied by having to hold a device at the right angle. He knew it couldn’t be a contraption that physically moved, which could potentially bump into things.

The solution? A really wide-angle camera that doesn’t make the subject tiny in the frame like GoPro, but would instead take its cues from Hollywood film principles. And it had to be 1,000 times faster than anything that came before.

The result was the smart camera feature—for which Cheung holds the patent through Facebook—that tracks and reframes the camera’s perspective. “If we zoom in on the person and frame them for you then that reduces some of that cognitive load…so you can just be more natural,” he says.

Some people are worried that if you talk about an idea that somebody’s going to steal it. But the bigger risk is that nobody cares about what you’re working on.

Facebook hired actors to walk around Airbnbs to get the data to develop AI that would track not just faces but tops of heads, shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips. It was important their sampling be diverse across gender, ethnicity and age. “Data sets are generally underrepresenting minority populations, older people, as well as babies and children,” says Cheung.

Creating a device to better connect with family back home was an especially good fit for developers in Silicon Valley, given almost nobody working there is actually from there. Cheung says Zuckerberg is a man of few words but he remembers the CEO’s initial reaction to their crude demo in 2017. There were some “wows” and then an assertive: “Let’s ship this thing.”

The tech behind Portal has since been picked up by Google, Amazon and Apple. “It was pretty cool to have that impact on the entire industry, where I invented this thing that, you know, is something that kind of defines these newer devices for video-calling experiences,” says Cheung, sitting in front of a wall with taped-up phrases like “Be bold” and “Build social values.”

He later developed Portal’s augmented reality storytime feature, which means a grandpa can appear on screen as the big bad wolf while reading Little Red Riding Hood.

Cheung focused on perfecting the software while collaborating on the hardware design with Regina Dugan, the former director of DARPA, the research and development agency of the United States’ Department of Defense credited with developing the first prototype of the internet (Dugan invented a portable device to detect landmines). He says working at a place as large and as influential as Facebook meant he could access cutting-edge research before its release—if you wait to act on findings once they’re published you’re eons too late.

“We probably had a two to three-year head start on some of these other companies. The technology that we were working on—even six months earlier—didn’t even exist,” says Cheung. “A lot of the best AI researchers in the world work here and we’re able to collaborate with them and actually build products that we hope at the end of the day actually help people.”

“My time at the University of Manitoba has actually led me here.”

In Cheung’s third year at UM, an undergraduate student research award had him exploring neural networks alongside electrical and computer engineering Prof. Witold Kinser. “This was, like, before people cared about neural networks,” says Cheung.

He was hooked and would go on to do his PhD in machine learning at the University of Toronto alongside computer scientist Geoff Hinton. “It was him and his students that basically invented deep learning and brought this to life. So, the whole reason anyone talks about AI now is because of this one group of which I was a part of,” says Cheung. “I only got into this space because of my time at the University of Manitoba.”

It was Hinton, along with computer scientists Yoshua Bengio and Yann LeCun, who kept working on this subset of AI when others passed it by, thinking it didn’t work, says Cheung. But with aligning advancements in computing and data, everything suddenly clicked. The trio became known as the Godfathers of AI.

“It actually all started to work in the early 2010s. And, you know, for the past almost decade now, has just been exploding in terms of use and expanding to different applications, different domains,” says Cheung.

Deep learning means a computer can understand not just that there’s a dog in a picture, but it can recognize the type of dog, where the dog’s looking and—if it were human—what language it speaks. But language is actually very tricky to capture with AI. Cheung offers a classic example with the sentence: You have a trophy and it doesn’t fit in the suitcase. But what if you instead said it like this: It didn’t fit because it was too big. Or like this: It didn’t fit because it was too small.

As humans, we understand which pronoun is referring to the trophy and which is referring to the suitcase. “But this is really difficult for a machine to understand. Like, you have to understand context,” says Cheung. “The field is really interesting and it’s progressing.”

Rest assured, he says, there is no impending risk of AI outsmarting humans. For evidence, he looks at his own kids. In the early days of developing Portal, Cheung would walk around the room while finetuning how the camera follows and zooms. “I would obviously get it wrong initially—it would start flipping out and start crashing. It did this a lot,” he says.

When Cheung’s eldest daughter was six-months-old, she’d be sitting on the sofa while he circled the room, training the camera. The toddler proved to be a far quicker study. “I was like…‘Oh, this is like smart camera 2.0 except this one was so much easier to build and was way better than the one on Portal,” he says. “It’s very quick how the kids surpass the intelligence of machines.”

When it comes to training computers through data, for machines to understand even basic concepts, you have to give them millions—even billions—of examples whereas a child only sees maybe a few examples.

“It takes a kid a little while to understand the first time they see a picture of a cat. But then later on when they get a little bit older you show them one or two pictures of a lion and then all of a sudden they can identify all the lions—whether it’s a drawing or real-life. They kind of make those associations but machines don’t have the same realization.”

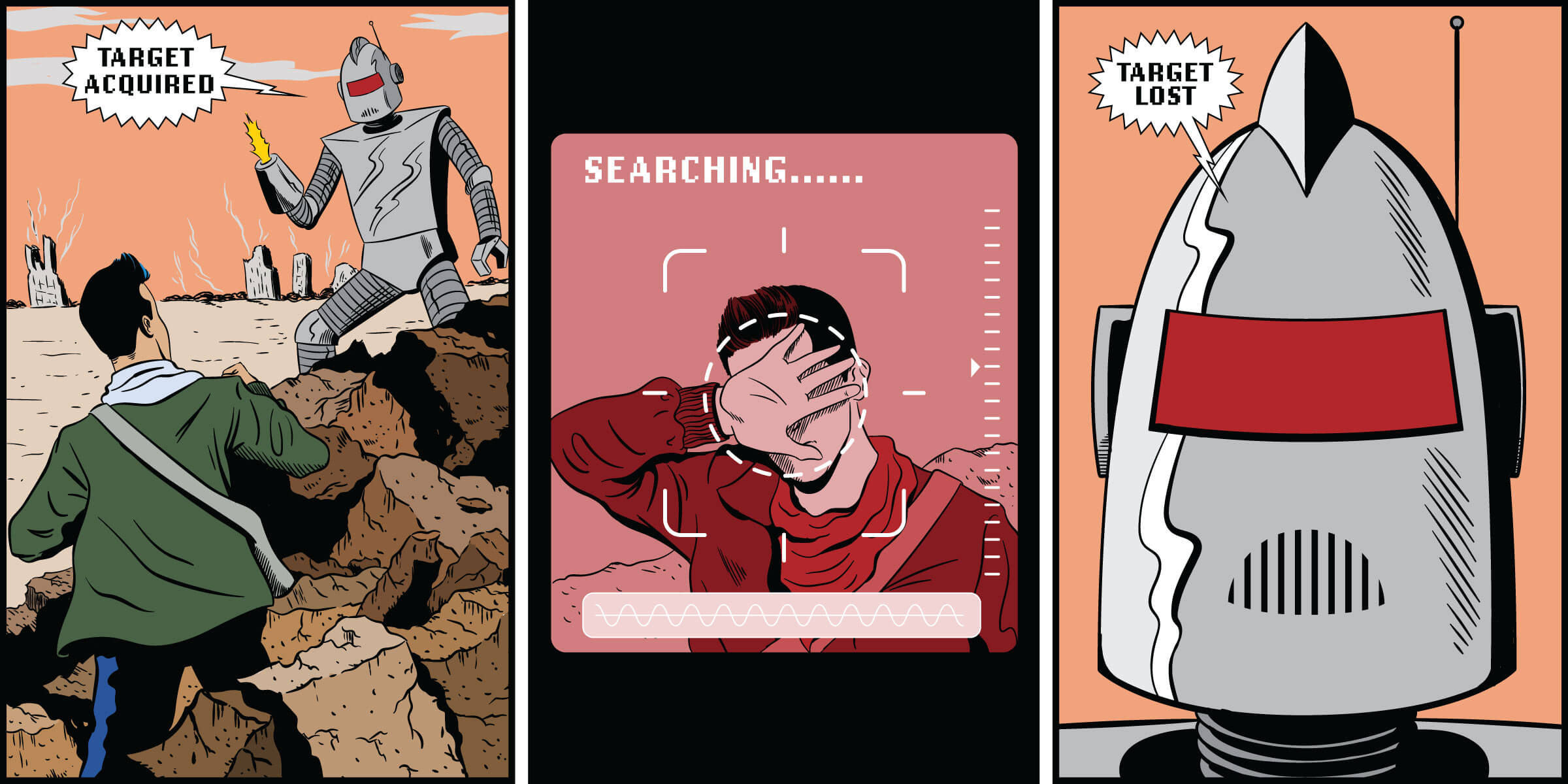

While much is said about the lurking dangers of AI, people working in the field are far less afraid, Cheung says. “AI is really, really dumb. It’s really dumb right now. It doesn’t understand. There’s no way it can become self-conscious and start taking over the world. It’s just not possible to do that right now. It might try to do that somehow if you program it to do that but there would be really easy ways to just break it.”

Say a robot is trying to hunt and kill people, you could just put your hand on top of your face—“Like this,” says Cheung, with his palm at his nose. “And all of a sudden you just disappear from the world and the robot would be, like, ‘I don’t know where Vincent is anymore.’ It’s really easy to trick them and kill them at this stage in AI.”

What does concern Cheung, though, is the biases within the humans feeding data into AI systems. Suppose you’ve developed an AI system that calculates hiring. “The AI system is going to do what it was trained to do and it will just hire more white males in their 30s, for example, even though a better qualified candidate might be a minority female in her 50s. It was just that they were never shown an example where the female in her 50s was ever hired because the human had these inherent biases that prevented them from doing so,” says Cheung. “So that’s where I think a lot of the danger is.”

He likens this AI to children who are home-schooled, and then shielded from everything in the world, who only know what their parent teaches them. No longer can you have a racist parent produce an unracist child or a parent who doesn’t recycle but a child who does. “If you’re not careful, the fallacy of humans is just going to get perpetuated in our children of AI,” he says. “They don’t have these safety nets to correct themselves. That’s the biggest short-term danger.”

The software itself is innocent. “At the end of the day, humans are at the root of the evil.”

Cheung says he has to stay mum on what he’s working on now for Facebook, offering only a vague mention of “next-generation of experiences” and what they believe will be tomorrow’s computing platform. It could be in commerce or in creativity, he hints, before dangling a final carrot.

It’s something, insists Cheung, that will “really make people’s lives better.”

I read this issue cover to cover because it was full of interesting articles. It was great to read about Justin Langan’s video project interviewing First Nations elders. He attended the high school in Swan River where I have taught. Thanks for all the info!

Kevin Penner (B.Ed. 88)