‘Would I Live or Would I Die?’

Fall 2021

Dahn Hiuni [BFA(Hons)/88] is a Los Angeles-based playwright, visual artist and academic, with plays produced in New York and art exhibited widely in the U.S., Canada and abroad. His most recent show, The AIDS Portfolio, offers a decades-long retrospective of his HIV-related work.

I enrolled in the School of Art at the University of Manitoba in the fall of 1984. I was 18 years old—a time usually associated with wonder, anticipation and hope. It’s also a time for one’s budding romantic life.

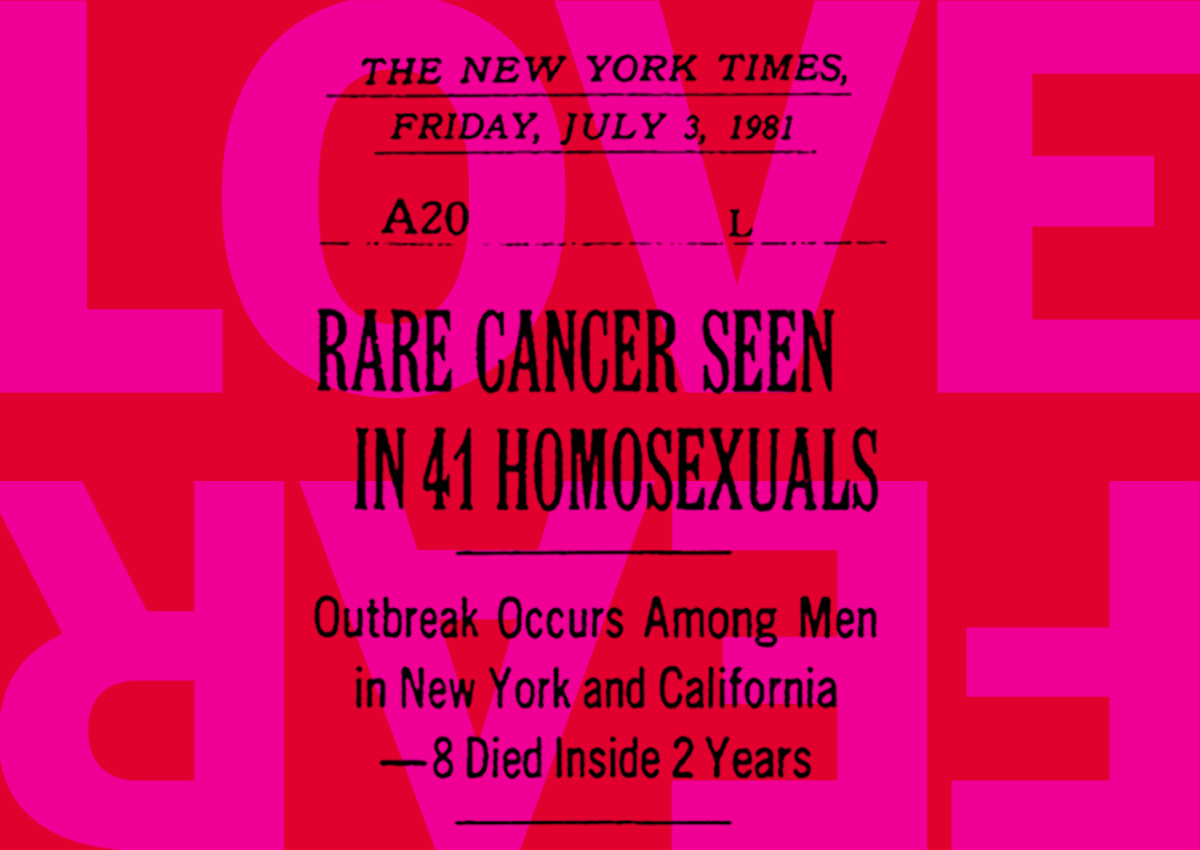

But my 18th year was marked by something else: persistent, unmitigated terror, triggered by a modern-day plague. This scourge seemed to be affecting my community—gay men—in particular and I found myself facing a new reality: Would I live or would I die young?

And so, in the early mornings before Ivan Eyre’s [BFA/57, LLD/08] drawing class, I would make my way to a Corydon Avenue clinic, the only one testing for this new virus. In the waiting room, my heart would be jumping out of my chest, my blood electric with stress, fearing I would test positive. I would then race to make it to class on time, to make beautiful drawings.

What followed was an agonizing two-week wait for the results. This was before American and French scientists had even devised a test for HIV, so the procedure involved being pricked with a dozen needles containing small amounts of various infectious diseases to see if you had an immune response. It was a very primitive approach in retrospect, but that’s all there was. I remember driving through Osborne Village on a cold October night, heading home from campus, and hearing the news that Rock Hudson had succumbed to this awful disease. I thought, ‘If a big movie star like Rock could die, surely I could die.’ At the same time, I was hopeful a high-profile celebrity’s death would help move things along.

Right away I knew an epidemic that’s sexually transmitted and disproportionately affecting gay men was not going to be good, neither from a public health nor a public relations perspective. Naturally, the disease became highly politicized, bringing out the worst in many—discrimination, homophobia, bigotry—couched in, and justified by, supposedly moral and religious conviction. It would be a mess for years to come.

This public health plight was very much about one’s private life: I was young, I wanted to date, I wanted to experiment, I wanted to fall in love. Why, for goodness’ sake, was this happening right when I was ready? Suddenly, having sex could literally kill you, and everyone was a suspect and a target. I remember thinking, ‘Well, at least I’m not in New York or San Francisco; it’ll be a while before this thing reaches Winnipeg.’

Dahn Hiuni’s works [clockwise from left]: Abstract for Ravel, mixed media on canvas, 1986 / Safe Painting (paint tubes in condoms on canvas), 1988 / Demonstrator, Montreal, 1993

Despite the hovering uncertainty, I continued with my studies and did well. I changed my direction from graphic design to painting, and I loved it. I was surviving, it seemed, from semester to semester. I remember being in the painting barn when I heard that Michael Bennett had died, the great choreographer and director of A Chorus Line, and my personal hero. An entire generation of vibrant, brilliant men—disproportionately from the arts communities—were dying in their 30s and 40s, and would continue to die until more would be done about this disease.

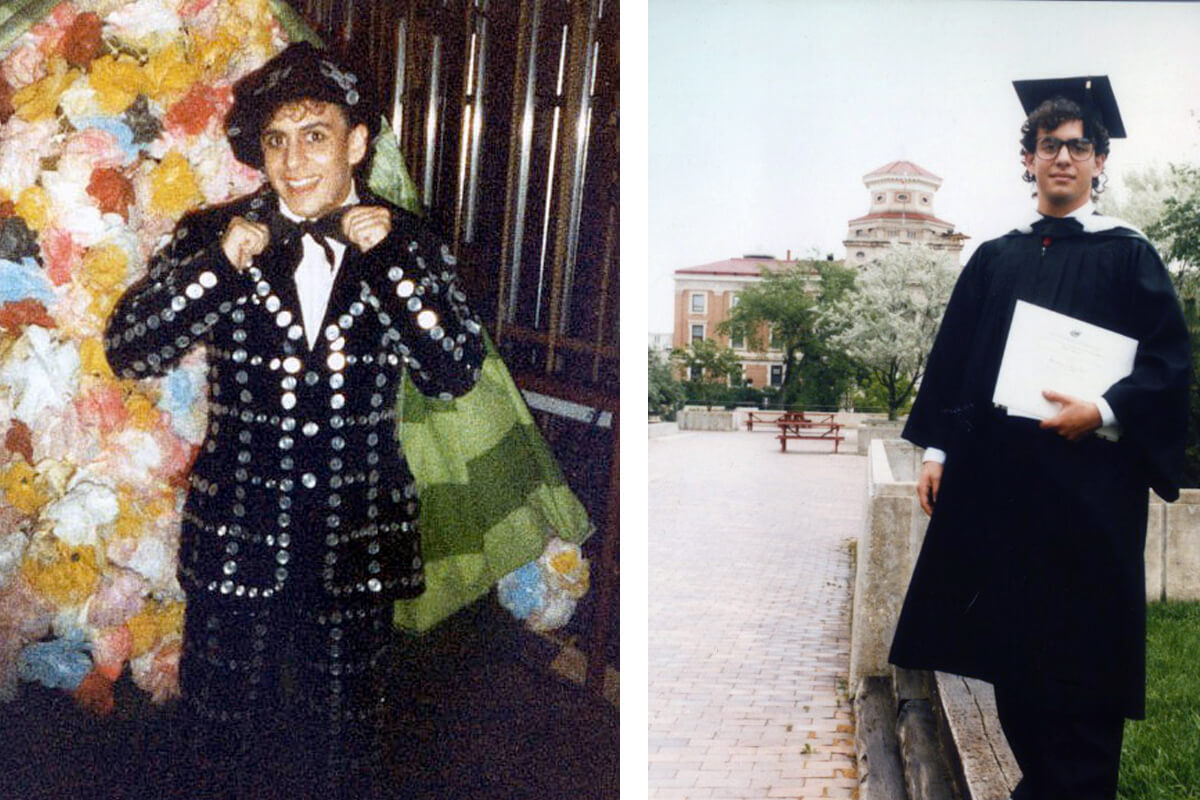

Aside from my art studies, I also loved theatre—musical theatre in particular. By day I would be on campus in the Fitzgerald building, and at night I would be performing at the Hollow Mug Dinner Theatre by the airport, singing and dancing to the joyous tunes of Cole Porter and Rogers and Hammerstein. In the summer of 1987 I was cast in the chorus of Rainbow Stage’s My Fair Lady.

Dahn Hiuni as a busker in My Fair Lady at Rainbow Stage in 1987, and upon graduation the next year

It was my first big professional production and, in retrospect, some of the most wonderful times of my life.

It was also how, at 20, I met my first boyfriend. He was from Toronto and he played Freddy Eynsford-Hill, the naïve young suiter of Eliza Doolittle. Most every performance, I would watch him sing “On the Street Where You Live” from the wings, fancying that he was thinking about me rather than Eliza. (The street where I lived was Assiniboine Avenue…) He was 30. He had an exquisite tenor voice. But he would be dead within five years.

On top of the grief and constant fear, I faced the philosophical-aesthetic dilemma of what I was going to make art about at such a time in history. I had gravitated toward abstraction, but I realized that making pretty, abstract paintings seemed irrelevant and self-indulgent in a time of crisis. My Jewish identity also made me think of my ethics and responsibility toward Tikkun Olam, the imperative to “repair the world.” And so I started to make art about the crisis, in particular how the disease affected art and artists. I guess I became a political artist, but one who tried to speak metaphorically, so as not to alienate his audiences.

Art Imitates Life, Performance on World AIDS Day, 1994, Penn State

In this performance art piece, I shuffled across campus at Penn State University, where I was a grad student, and used an IV bag of my own blood as the paint on a white canvas. Removing the IV from my arm and using it to pierce the canvas, I let the blood soak in as I walked away in silence.

I lost several friends to AIDS. From the late 1980s ’til this very day my art and writing is shaped by these experiences. I focus more on playwriting now than visual art, but the message is the same: compassion. This was my plague and my nightmare, but everyone is going through their own. The common takeaway is kindness, understanding, compassion for all.

Of course, one plague per lifetime would have been enough, but here we are again. In America, when the coronavirus pandemic quickly generated a warm and fuzzy slogan “We are all in this together” I couldn’t help but feel a little resentful because that was definitely not the case with HIV. But we have evolved. Perhaps now we know not to blame people for their illness (the elderly, the immunocompromised, the Chinese.) I’m glad I survived and lived to see the day where this is the case.

We all know this won’t be the last pandemic we see. The more we encroach on nature and on animal habitats, the more zoonotic transfer will occur. (It is likely HIV jumped species in Africa sometime in the 1940s, when hunters increased their slaughter of green monkeys for bush meat.) Instead of focusing so intensely on who is getting infected, we should focus moreso on the disease’s source and cause. This way we could all help each other to lead more sustainable lives on this Earth, with less blame. Here’s to your health. Here’s to everyone’s health.