Storyteller

Spring 2021

Michael Posner [BA/68] is an award-winning writer, playwright and journalist, and the author of the bestselling Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years, Vol. 1. His previous eight books include the Mordecai Richler biography The Last Honest Man, and the Anne Murray autobiography All of Me, both of which were national bestsellers. He was Washington bureau chief for Maclean’s magazine and also managing editor of the Financial Times of Canada. He later spent 16 years as a senior writer with The Globe and Mail.

I only met Leonard Cohen once.

I use the word ‘met’ with the most elastic of interpretations. It was about 2006. I was leaving a hotel in downtown Toronto one afternoon, and he was pacing the sidewalk outside, wearing a beige London Fog raincoat, and waiting—I presumed—for a limousine to pick him up. I looked at him and he looked at me, and our eyes then conducted a brief, silent conversation. ‘You’re Leonard Cohen,’ my eyes said. And his eyes replied, ‘Yes, I am, and I know that you know that I am.’

Soon after, I wrote him a note—an email to his famous address, baldymonk@aol.com. The address was Cohenian word play, alluding both to the Zen centre on Mount Baldy, an hour east of Los Angeles, where he had long practiced and, indeed, been ordained, and to the shaven head that monks traditionally sport.

I had recently finished a book on the late Canadian novelist Mordecai Richler—an oral biography—and thought Cohen might lend himself to similar treatment. Oral biography occupies a small but inviting room in the libraries of non-fiction. It’s biography delivered not through the focused, interpretive lens of the author, but in the myriad voices of the people who actually knew the subject. Instead of a single point of view, there are scores—even hundreds—of points of view that are often in conflict. This approach forces the reader to decide where the balance of truth might lie.

I laid all of this out in my pitch note to Leonard. Having his consent would open many doors that might otherwise remain closed. His reply was prompt, succinct and gracious, but gently dismissive. He was then embroiled in litigation with his former personal manager—she’d been accused of siphoning some $5 million US from his bank accounts—and he simply did not have time to engage in such a project. Perhaps one day down the road, he intimated.

It was not to be. Down the road, Cohen soon embarked on what became his most successful period of international touring, lasting the better part of five years—in part to replenish the shrunken coffers. Thus, it was not until he passed, in November 2016, that it occurred to me to resurrect the oral biography idea. I would have to proceed without his blessing, but—I believed—there would still be many people, not previously heard from, who would be eager to tell me their stories, memories and observations of Leonard.

Cohen was once asked about how he translated the Gabriel Garcia Lorca poem Little Viennese Waltz into the poem/lyric that became his song Take This Waltz. He said it had taken him 150 grueling hours to complete and that, had he known when he began that he was beginning a trek along the Great Wall of China, he might never have started.

I don’t know if I would say precisely the same thing about the process of compiling Leonard Cohen—Untold Stories. But I do know that one interview typically led to two more, and two more often led to four more, and pretty soon I had amassed a great deal of new information and dozens of interviews. By December 2019, about three years after I began, I was somewhere north of 500 interviews. Indeed, the original manuscript came in in excess of 600,000 words. Fortunately, Simon and Schuster then decided to carve it into three separate volumes, to be issued over three years. And although it was in many respects a grueling exercise, I can honestly say that I enjoyed virtually every moment.

If this book, and the two to follow, succeed in delivering Leonard Cohen in all his multi-faceted complexity, perhaps I might one day be so lucky as to again behold his ghostly presence on the street, watch him raise his finger to his fedora and offer a brief salute.

AN EXCERPT FROM Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years, Vol. 1

(But first, some context…)

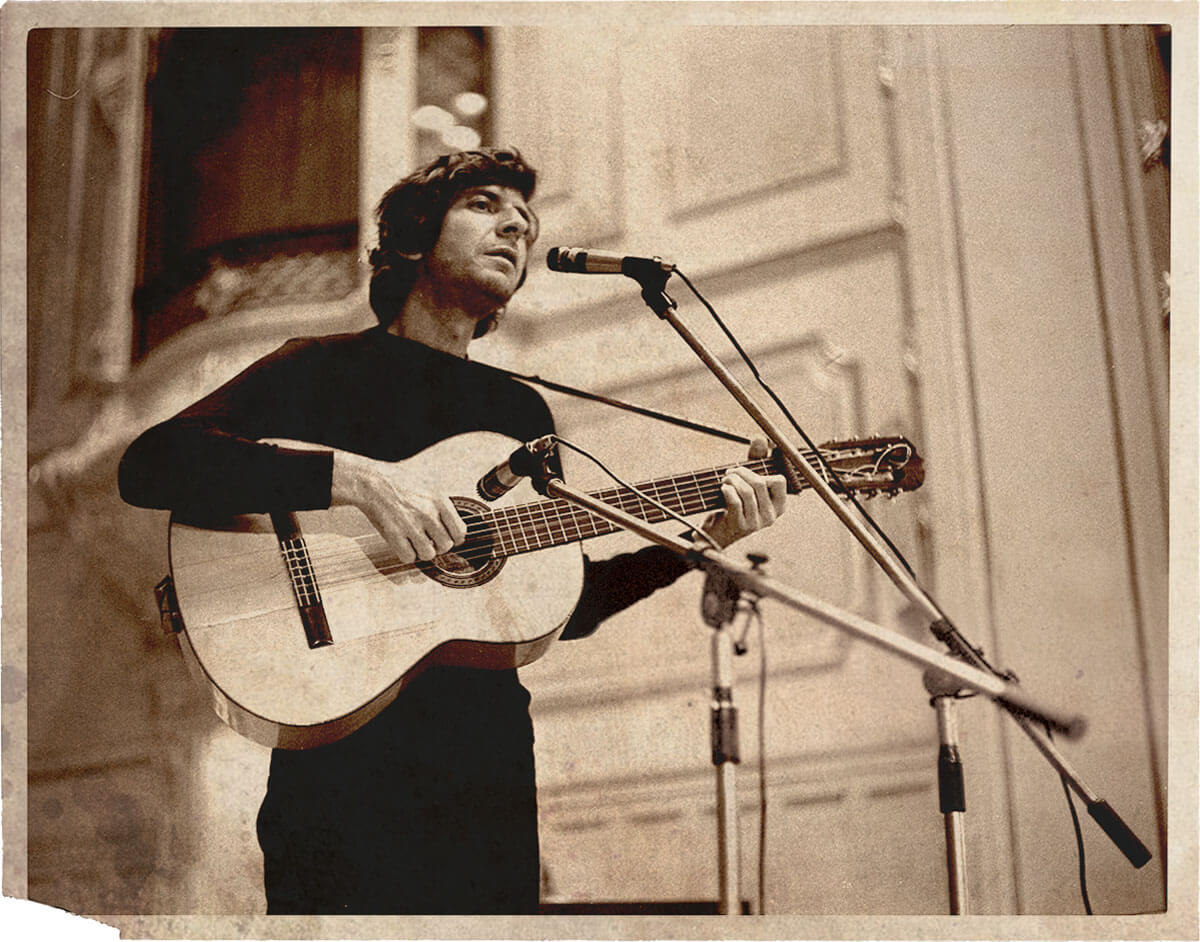

In December 1966, Leonard Cohen performed several concerts in Edmonton. It was his success there—what Dr. Kim Solez called “his first real taste of celebrity, groupies and standing room only audiences”—that cemented his determination to make the shift from poet-novelist to singer-songwriter. He articulated his ambition in a Dec. 4, 1966, letter to Marianne Ihlen, saying that he could not support himself and Marianne as a novelist and poet. He would have to be a singer-songwriter. In the letter, Cohen writes, “I must be a singer, a man who owns nothing…. I know now what I must train for…. Darling I hope we can repair the painful spaces where uncertainties have us. I hope you can lead yourself out of despair and I hope I can help you.”

Not long after his Edmonton sojourn, Cohen flew to Winnipeg to perform in Taché Hall at the University of Manitoba—his first concert as a fully committed singer-songwriter. Cohen had appeared there three years earlier, reading poetry to guitarist Lenny Breau’s accompaniment. The student union’s events coordinator sent Cohen an invitation.

MENDL MALKIN: I asked if we could set up something like that again and the answer came back, “No, but he will come and perform.” I was expecting a poetry reading and I was totally in the dark about what the show would be.

JACK BIDNIK: Leonard arrived alone, wearing a grey trench coat. Nobody came out to meet him, so I and a few others greeted him and showed him to the backstage area. It was a small audience, about seventy-five. The atmosphere was a bit awkward because, although his songs had been sung by [Judy] Collins, few except the cognoscenti had heard of him. Then he handed me some sticks of incense to hand out, saying if the audience had these, we’d have half a chance. The sticks were soon lit, and I took my seat. Then someone noticed there was nobody to introduce him. This was ridiculous, so I got up onstage and announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Leonard Poet.”

MENDL MALKIN: Jack also said, “You may be wondering why I’m introducing Leonard Cohen. And the reason is, I’m the only one here wearing a tie.” He sang the whole concert—he did not read. Everyone was spellbound. It was magical.

MARTIN LEVIN: My strongest memory is of him singing “Suzanne.” Hypnotic. Don’t recall any Dylan betrayal effect, that he’d abandoned poetry for pop.

High school student Alan Mendelsohn also attended the concert.

ALAN MENDELSOHN: I was seventeen and we were all listening to The Beatles and Stones, the Lovin’ Spoonful, a far cry from Cohen’s haunting tunes. But I found it difficult to engage with him. He didn’t [then] have that charming stage presence—more like a brooder; mysterious. I don’t remember any patter. I don’t remember him relating or flirting with the audience. But he had a mystique. He was alone on stage with his guitar looking the role of a bohemian. The audience was in awe, transfixed by his persona. He sang “The Stranger Song”—I wasn’t sure what he meant but it sounded very deep.

After the concert, the NFB film, Ladies and Gentlemen, Mr. Leonard Cohen was screened.

JACK BIDNIK: I recall watching him watching himself in his movie, thinking how unusual a scene it was. We had some conversation on schizophrenia in poetry. He was somewhat bemused when I told him I was in favour of it.

MENDL MALKIN: Afterward, backstage, about thirty kids were asking questions. Someone asked him about building character and he recommended three things that were good for you—LSD, divorce, and a nervous breakdown. I don’t think he was on LSD at the time. He was too coherent.

JACK BIDNIK: Afterward, Jim Donahue, a folk singer, and I, and our two dates, drove Leonard Cohen to his motel. He then decided he would take a cab direct to the airport.

An insightful review in the university newspaper—by Michael Mitchell—noted that Cohen “made no attempt to put himself over…The audience was not graced with a smile, a sign of friendship or any emphatic gesture…The result was that the words themselves became stark, powerful and at times embarrassingly naked…The poetry spoke for itself. It alone was on exhibition. No attempt was made to sell it…It was an evening…devoid of the con.” If the Leonard Cohen of 1967 had drafted a foundational mission statement for his music, it would have come pretty close to that.

* Excerpted from Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years by Michael Posner. Published by Simon and Schuster Canada. Copyright © 2020. All rights reserved.

Where are they now?

UM students taking in the Leonard Cohen concert on the University of Manitoba campus some 55-years ago went on to successful careers. Alan Mendelsohn [BA/70] was a long-time documentary producer for the CBC before launching his own production company, Just A Minute Words & Pictures. Mendl Malkin [BA/69, MD/73] became a family physician and is now retired in Toronto. Martin Levin [BA(Hons)/69] became the books editor at The Globe and Mail and one of the most influential figures in Canadian publishing.