Self Portrait

Fall 2021

When multidisciplinary artist Lori Blondeau shared her mother’s experience of residential school as performance art, her mom was right there in the audience.

For the exhibit, the UM School of Art assistant professor—and 2021 recipient of a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts—sat quietly in a chair behind a makeshift chain-link fence, knife in hand, shaving the bark off a poplar branch. The daughter of activists, Blondeau is Cree, Saulteaux and Métis, and this inaugural performance was part of her master’s degree at the University of Saskatchewan.

To gallery spectators, she recited how her mother told her she hated the smell of disinfectant and bleach in the brick building she spent most of her days cleaning. She had told her it was her grandmother who most often came to see her—it was too much for her own mother to bear—and they were forced to visit with a fence between them. Her grandma would toss over a sweater and she would bury her face in it, breathing in the aromas of home: poplar burning in the wood stove.

So when Blondeau’s mom could smell the wood shavings in the gallery, she broke down.

“I had to stop the performance,” Blondeau recalls.

She and her sisters took her mom aside to a private area and asked if they should end it early. She said, “No.”

When Blondeau came back out, the performance was to continue by her locking audience members inside the fenced area she had created. “But when I looked at everybody in the fenced area, everybody was crying and I thought, ‘I can’t. I can’t lock them in here. They’re already having a hard time.’ That really changed a performance. I never lectured about that piece because it was too raw for me.”

photo courtesy of University of Saskatchewan

▸ Watch Blondeau’s recent WAG performance of Are You My MotherBut as an artist and as an educator Blondeau says she’s learned how important it is to reveal her vulnerability. This felt particularly true during the pandemic. On the one-year mark of teaching remotely, she felt she needed to be totally candid with her students about the toll of being distanced from human interaction for so long.

“It was really emotional for all of us and I cried. And it was just about being able to feel vulnerable with them and letting them know that I was feeling the same things as them,” she says. “It was just those moments of vulnerability and me feeling okay to be vulnerable as their teacher, you know? The art they made was incredible—and just how safe they expressed that they felt within the class.”

In her own award-winning works, whether it’s performance or photography (she always puts herself in the image), activism meets art. Here, Blondeau reveals the powerful personal stories behind her pieces that span decades.

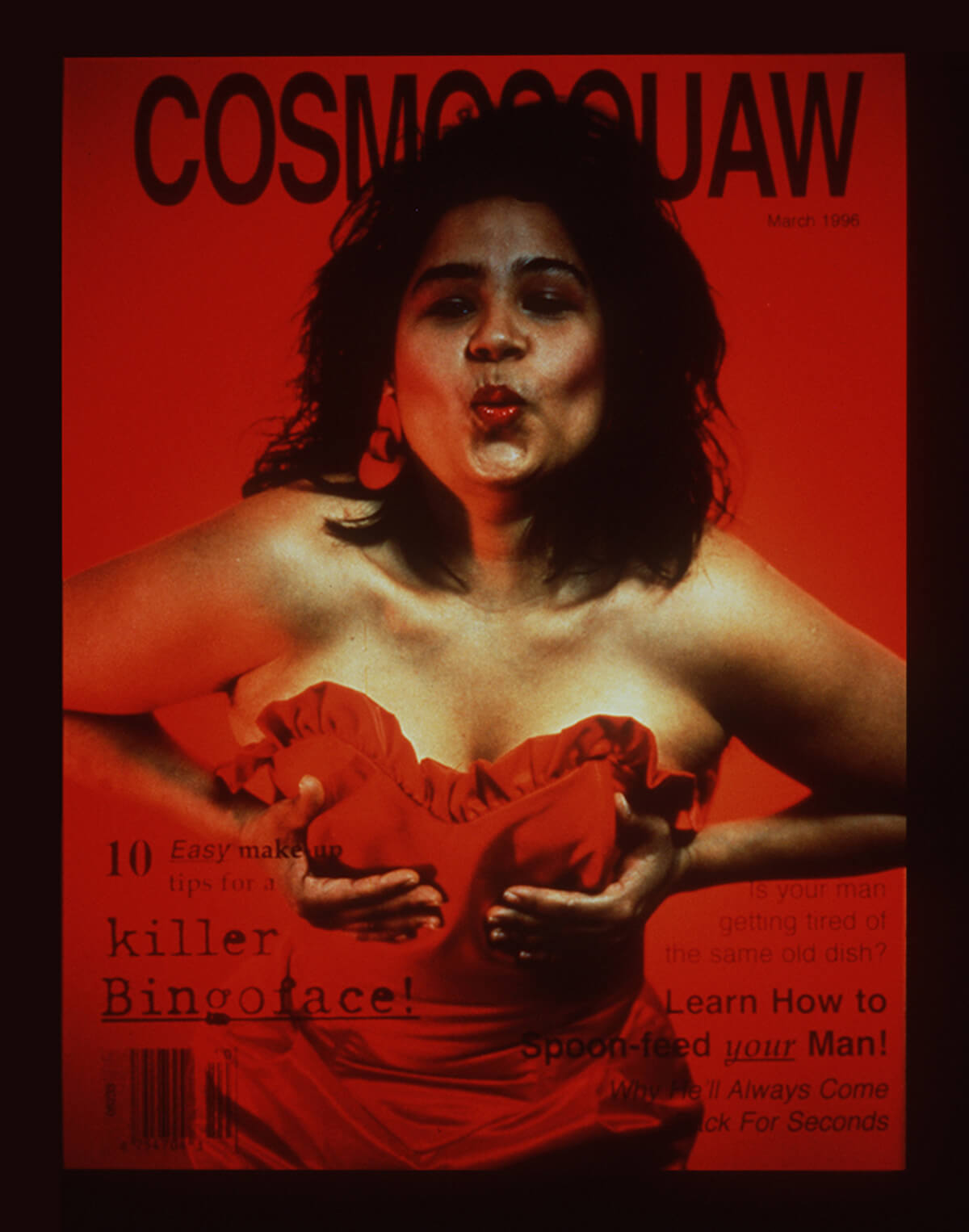

“I wanted to make a Cosmopolitan magazine but for Native women.”

Cosmosquaw (1996)

In the 1990s, Blondeau worked at a Montreal shelter for Indigenous women and had a co-worker who would often come in with the popular women’s magazine.

“I couldn’t understand why she would read it because it was a very white magazine.”

Blondeau knew then she wanted to do a parody of Cosmo for Indigenous women, put herself on the cover, and call it Cosmosquaw.

“I grew up in Regina, which was a very racist place to grow up, and I grew up being called ‘dirty squaw’, ‘ugly squaw,’ ‘f*cking squaw.’”

She recalls one particularly traumatic Saturday afternoon when she was 16. Blondeau was hanging out at a park with friends—all of them non-Indigenous—when a man from a distance yelled to her, “You f*cking ugly squaw!”

She left for home in tears and relayed what happened to her grandma, who told her “squaw” was a word that carried a lot of beauty and power, simply meaning “woman.”

“That was the first time I had to really think about: What did squaw mean?”

Blondeau learned the word comes from the Rappahannock people, a nation in New York state who were among the first to be in contact with white people. “As settlers started coming west and there was more resistance, the word became bastardized and then it took on this negative connotation for Indigenous women. I want to—I’m not going to say ‘reclaim’ because I don’t think that we need to reclaim any word that comes from an Indigenous language—but re-appropriate it.”

It made perfect sense to pair “squaw” with “cosmos,” which means at one with the universe.

“That’s what I think an Indigenous woman is.”

“It’s like the rocks are having their press conference.”

Stones from my Kokum’s House (2021)

While watching so many televised COVID-19 Manitoba media briefings from the living room of her Point Douglas house, Blondeau pondered—and became nostalgic for—ideas of home.

She had recently visited her family’s community of George Gordon First Nation in Saskatchewan, bringing back rocks from a spot of land that’s taken different forms over the years. The sod house her maternal grandparents built in the 1930s was eventually burned down, likely by partiers in the area, says Blondeau. Long before that, it was where her ancestors would meet.

They left behind teepee rings outlined with rocks that she remembers from family camping trips there as a kid. On this visit, she noticed remnants of a rock garden her kokum (grandma in Cree) had built around the house’s old perimeter.

“And I asked my mom if I could take one of her rocks and take it back to Winnipeg, which I did. And I didn’t realize how big the rock was until my brother dug it up for me.

“I’ve always worked with stones in my practice…and I think that comes from being influenced growing up and seeing those teepee rings and seeing that they are this evidence of our history on this land.”

Rocks are considered to be grandfathers, says Blondeau.

“It’s just about what they hold within them. Like, if rocks could tell the story, if they could talk, man, we wouldn’t have to be worried about our history as Indigenous people being misinterpreted.”

“I wanted to look graceful.”

States of Grace (2007)

For this exhibit—performed in Venice, Italy—audio played of Blondeau reading seven stories of birth, death and near-death. As the narrative filled the air near the famous canal, she braided her hair and then cut one off for each story told.

“For me, the word was really interesting, how it has this dichotomy to it. You either walk in grace or fall in grace.”

“It was about being like a monument.”

Asinîy Iskwew (2018)

A 400-tonne boulder known as Mistaseni (big rock in Cree) inspired this photograph. Despite protests from Buffy Saint Marie and others, the government blasted this ceremonial rock with dynamite in 1966 to make way for southern Saskatchewan’s man-made Lake Diefenbaker.

“They ended up blowing it up in the middle of the night, you know, when nobody could be there,” says Blondeau.

For generations, Mistaseni was a huge gathering place for the Cree, Assiniboine and Saulteaux people, with up to seven miles of teepees.

Blondeau draped herself in red velvet because it’s the colour of power, of blood, of life.

In 2014, divers found remnants of the rock under the water. Here, Blondeau stands on a recovered portion of Mistaseni.

“It’s a piece that’s just about sustenance and how fast, as Plains Indians, our food, our way of eating, changed.”

Sisters (2006)

For this performance piece, Blondeau sat in front of a video of her crushing berries with a rock. She also gutted a fish and ripped red cloth before stepping forward from the projection with a lunch box—and eating 12 McDonald’s cheeseburgers.

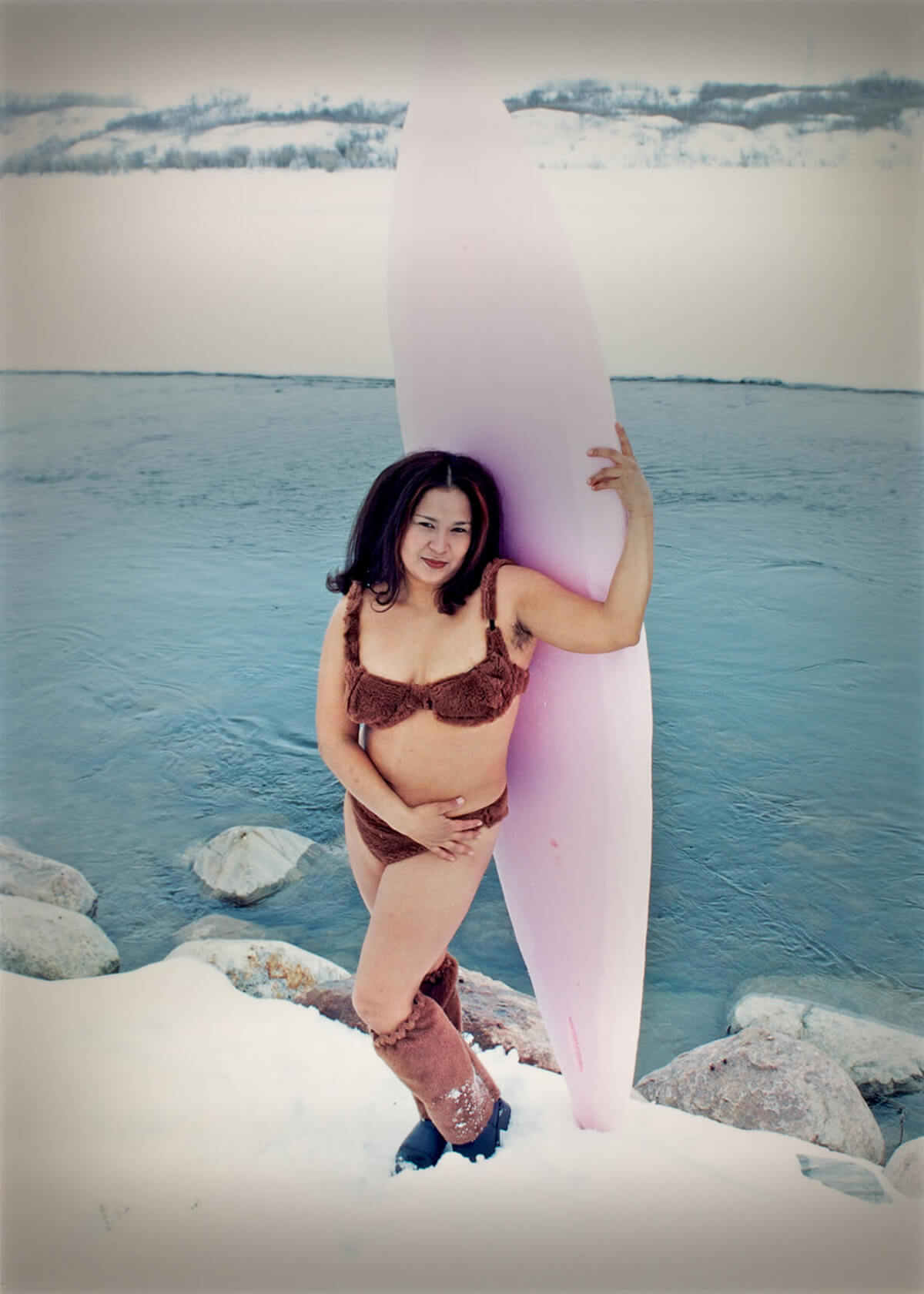

“Growing up in the 60s and early 70s, there was all these surfer movies, you know, with Elvis Presley, and I remember just falling in love with those and wanting to be a surfer.”

Lonely Surfer Squaw (1997)

Knowing only life on the Prairies, Blondeau always dreamed of “getting out of here” and let her imagination fly with this pop culture parody of one of the old movie postcards she collected.

The river stood in for the ocean and the snow for the sand.

“And when you’re on the Prairies, you’ve got to have a fur bikini.”

“Because I make work with my own body, I always think in those terms. Like, how would I place myself in a landscape and what am I trying to say?”

A Tribute to Demasduit (2021)

This 16-foot banner represents the story of Demasduit, one of the last of the Beothuk people who lived on the coast of Newfoundland during the 1800s. She was imprisoned by government and forced to draw seven maps of her peoples’ territory.

Each of the artists commissioned for this Toronto exhibit were given one of these archival maps as inspiration. Blondeau’s showed where Demasduit’s brother and sister-in-law were killed one horrible winter.

Art brings light to parts of history unknown to a lot of non-Indigenous people, says Blondeau.

“It gives me a language that I know how to speak and that I can bring to a very broad audience to tell a story or make a statement,” she says. “That’s just what I do. It’s work.”

Pease tell Ms. Blondeau that I absolutely LOVED this piece, I loved learning what she had to share: it was painful, but beautiful all at the same time. It is the most meaningful and appreciated performance art I’ve seen. Thank you for sharing this! I LOVE this magazine as well: I read it cover-to-cover and always learn so much.