The women move slowly, bent slightly as they tentatively enter the room at Panzi Hospital’s Maison Dorcas aftercare unit, as if making themselves physically smaller might ease the agonizing trauma they have endured.

Panzi Hospital in Bukavu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), was founded by gynecological surgeon and 2018 Nobel Laureate Dr. Denis Mukwege. It treats war atrocity survivors in a region where rape is a weapon of conflict and leaves women with devastating internal and external injuries, along with unimaginable psychological scars.

There is a room there where another kind of caring treatment happens.

A recording studio.

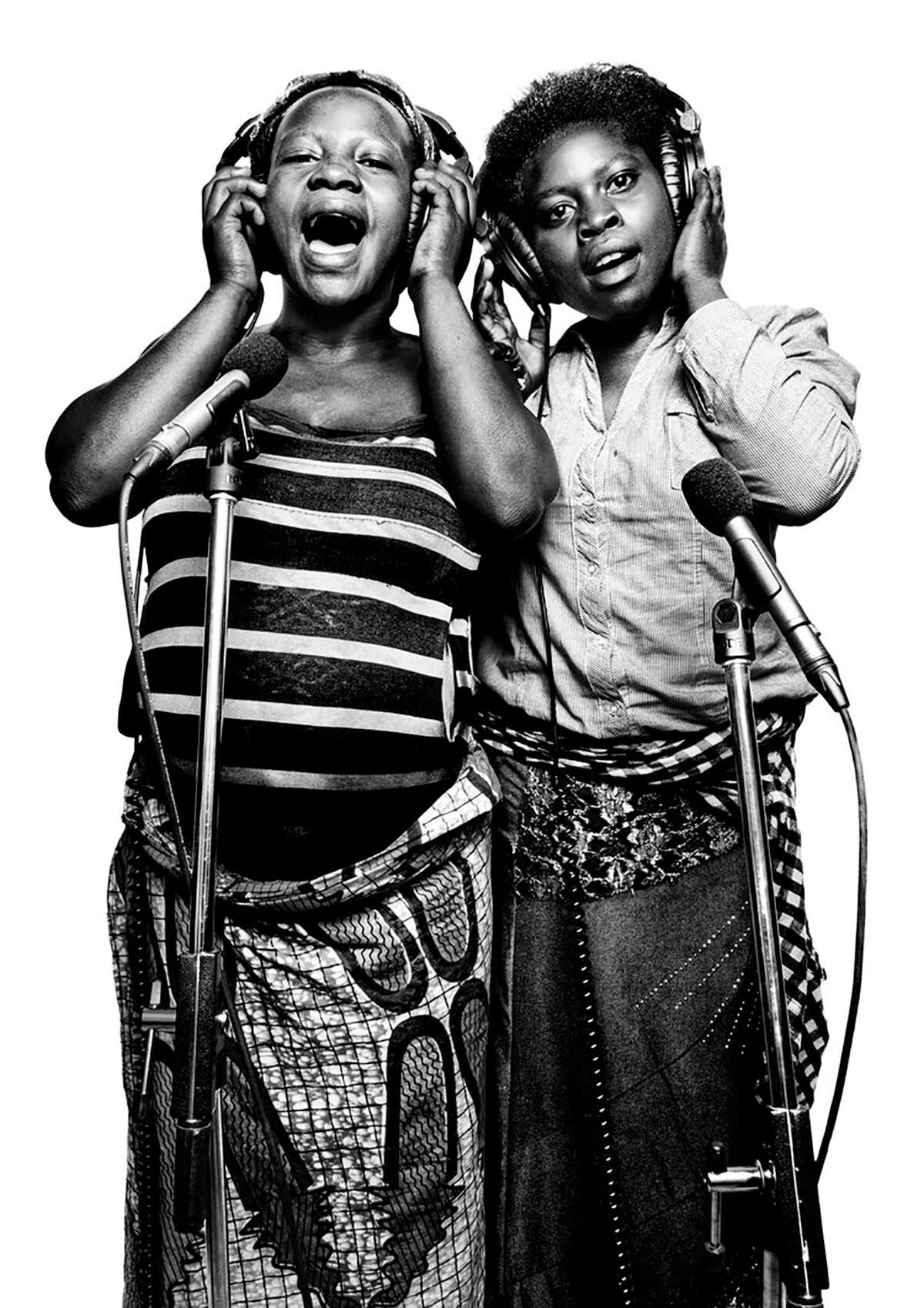

Imani and Sara, photographed before the COVID-19 pandemic, came to Panzi Hospital for care. Imani [left], pictured at eight months pregnant, says her parents didn’t believe she was raped. Sara was on her way to the river to wash her clothes when two men sexually assaulted her.

The Healing in Harmony music therapy program was created by Winnipeg music producer Darcy Ataman [BA/96]. It’s an arm of Make Music Matter, the charity Ataman started in 2006 to help marginalized people through song.

Since Ataman began Healing in Harmony in Rwanda in 2009, more than 5,000 people, primarily women, have completed the four-month therapy program in seven countries: DRC, Rwanda, Uganda, Guinea, South Africa, Turkey and Peru.

Canada will soon be the eighth, with the launch of a Healing in Harmony program in Manitoba’s Fox Lake Cree Nation. Band leaders hope it will help bring healing to struggles arising from poverty and isolation, as well as painful generational trauma. A report issued by the Province in 2018 revealed allegations of sexual abuse committed by some Manitoba Hydro workers in the community as far back as the 1960s.

Healing in Harmony are community-based initiatives, run by local teams and led by a staff psychologist and music producer following a structured program.

The participants are never referred to as patients or survivors.

They’re called artists.

Their emotions and stories become lyrics and then songs. Each one is performed and recorded by the entire cohort, explains Ataman.

“The producer is helping to pull out people’s stories, which turn into lyrics and melodies. While it’s happening, the psychologist is there. And while that process is going on, we interject therapy, like cognitive behavioural therapy,” he says. “And in a way, that’s almost not even noticed. They don’t come in thinking, ‘I’m going to my doctor’s appointment or therapy appointment,’ which still has a lot of stigma. They come in thinking, ‘I’m going into the studio. I have my own notebook with lyrics and rhymes.’”

“

They don’t come in thinking, ‘I’m going to my doctor’s appointment or therapy appointment,’ which still has a lot of stigma.

”

Artists are scored for PTSD, anxiety and depression at the beginning and end of each program. The results are tangible, measured by globally recognized standardized tests, including The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.

“We can literally quantify that reduction of trauma,” Ataman says. “They regain their sense of self. I see it [too] from the artistic standpoint.”

Ataman, 46, is often an observer at the recording sessions and graduation concerts. He sees the remarkable transitions. Feelings of stigmatization lift as participants go from “half-coma” states in the earliest days to emerge as confident artists. They are empowered, dancing and joyful. They feel like rock stars, he says. Told there may be perpetrators in the crowd at a concert, they reject the psychologist’s suggestion they perform in another community. They won’t be moved.

It’s not always about the singing. “Maybe she just wants to hold her friend’s hand,” says Ataman. Sharing stories and learning other women have been through similar experiences breaks isolation and eases stigmatization.

It’s what Ataman called “re-framing their past while carving out a new identity,” in a blog post from one recording session.

The songs have titles like “My Body is Not a Weapon,” with the lead vocal performed by the songwriter, Sandra. She was raped, becoming pregnant and contracting HIV. Sandra sings that it’s okay for her to have new dreams, a new life. She doesn’t have to live in pain. She can be a doctor, a lawyer, a president and, when she is, this is how she’ll fix her country.

“The Criminal Father” calls out abusive, repressive men, not only those who perpetrate rapes but those who allow them to continue.

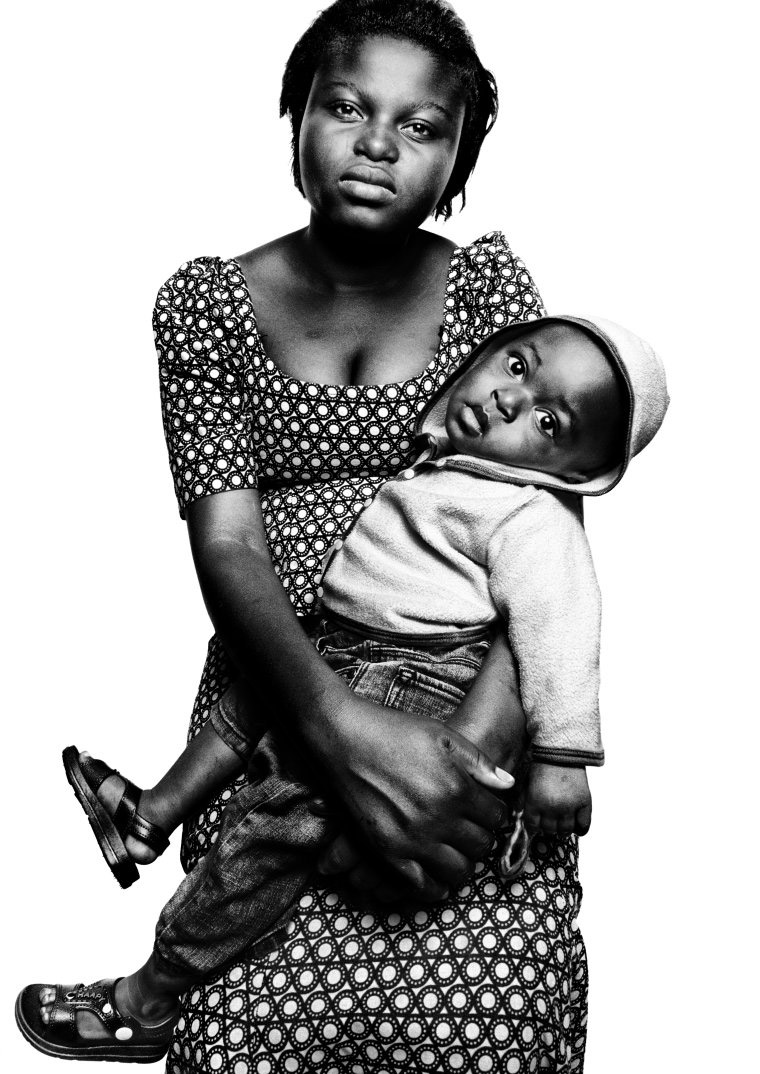

Esther is a Healing in Harmony participant and mother to her son, Josue. She was abducted by militia members from the rebel FDLR while fetching water in a forest by her home. She was held captive for three days before she was able to escape.

Teenage artist Esther was raped by rebel soldiers. She had two children as a result and was unable to bring herself to care for them. Ataman saw her, after performing at her graduation concert, go over and pick up one of her babies for the first time.

The songs also have an unanticipated effect on the soldiers. Healing in Harmony releases are played on regional airwaves, which have considerable reach in a place where everybody seems to have a transistor radio. The military has called the station to complain, demanding they stop playing them. The requests are ignored.

That’s a powerful thing for the artists to hear.

“Those women who wrote that song and heard that loved that,” Ataman says.

He knows he’s akin to an alien as he sits in the makeshift recording studios, a white guy from Canada, covered in ink in a place where tattoos are scarce. “Pretty much from Mars,” he says of himself. “I wonder, how do they think I see them, you know, who’s this weirdo sitting in the back, taking notes?”

So, he asked them. One woman responded: We used to think you saw us as without value because of what happened to us. But now I think you see us as artists.

“So that, to me, sums it up,” Ataman says. “That could be my epitaph, for crying out loud.”

“

There was not one frivolous song in the bunch.

”

The son of a Holocaust survivor in Ukraine, Ataman’s social conscience was stirred early. He learned the value of empathy when he was barely five years old, listening to his father’s repeated stories of his own childhood traumas during the Second World War. Speaking about it seemed to somehow help his father cope.

Ataman is incapable of being a bystander.

While he was filming a documentary, Song for Africa, he went to Nairobi’s Kibera slums, where more than one million people live “without any provision whatsoever.”

“That opened my eyes in terms of how great a need in the world there is, for the first time seeing that injustice gap,” he says. He started a scholarship program. That led to personally funding and fundraising for other social projects in Africa.

In Rwanda, he saw the horrific poverty and violence at Gikondo Transit Center in Kigali, where street kids are detained with adult criminals under the pretense of rehabilitation. He heard their cries as they were attacked in the dark and provided testimony to help to shut the facility down.

The idea for Healing in Harmony came to him as he led a Make Music Matter project in Rwanda in 2009, where he and Grammy Award-winning Canadian producer David Bottrill worked with Canadian and Rwandan musicians for the charity album Rwanda: Rises Up! On a day off, they took the recording equipment into a village to give local kids a chance to make music.

Everybody showed up. More than 70 young people wrote and recorded their own songs in a one-room school in a single day. The place was packed with kids, some waiting up to nine hours for their turn to perform.

Renown photographer Platon captured this image of Healing in Harmony participants, along with the other portraits accompanying this story. Platon founded the non-profit organization The People’s Portfolio, shifting his lens to support human rights efforts across the globe. Darcy Ataman is now working on his second documentary score for Platon, acclaimed for his photographs of world leaders and pop culture icons—from Barack Obama to Prince.

Ataman was astonished by what he heard. They sang about the toll and stigma of AIDS and HIV among their families and in their village. Young women sang about not wanting to sell their bodies just to survive.

“There was not one frivolous song in the bunch. And we didn’t give them any direction on what to write about. This was just what was on their minds,” he says.

“I distinctly remember walking outside this little one-room school, sitting on the grass and thinking: There’s something here. This is our thing.”

He knew music was a common global language and a way to express emotions. Perhaps it could also heal.

The idea came easily. The hard part would be putting it into practice.

“I come from a music and art background, professionally. So, I always believed in it. But every new step, I was always met with people saying, ‘Well, first of all, it’s never gonna work and second, who cares?’”

Ataman knew little about fundraising and program development. He was undeterred and kept educating himself while relying on his talent for being tenacious.

“I did learn all this stuff myself, the hard way, on the ground. So, it took about three years of honing the idea. Every problem—we didn’t cut any corners at all,” he says. There were needs assessment studies in communities, baseline surveys, ongoing work on the program model while securing funding partners.

“To be brutally honest, the last 10, 12 years have been a complete blur,” he says.

He’s a well-connected, recognizable name in the music business, with multiple JUNO Awards nominations and collaborations with artists like DJ Jazzy Jeff and the late Levon Helm of The Band. He’s also lousy at taking no for an answer. Together, that makes him an ideal charity CEO.

“I won’t cop to having many skills but that—I call it the polite pest routine…knowing when and how to bug somebody. And it’s just sheer tenacity. It’s amazing what you can do if you just never give up no matter what the circumstances.”

He was so anxious to partner with Mukwege, a man he knew by reputation and greatly admired, he practically slept in Panzi Hospital’s halls to make inroads. He is clearly in awe of the surgeon, who is often at risk of assassination for the crusading work he does.

“There’s humans and then there’s a notch above, because some people in the world are just not quite human. And he’s just one of those guys,” says Ataman.

The lessons he’s learned from Mukwege, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his human rights work to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war, can’t be numbered. There are lessons about humility, service, dedication and Mukwege’s uncanny ability to see multiple steps ahead of anyone else. But the lesson that has stuck with him most powerfully is about resiliency. He wonders how Mukwege found the courage to go on after Tutsi rebels killed more than two dozen patients in their beds in an attack on the hospital where he was working in rural Lemera, in 1996.

Healing in Harmony had its first Panzi Hospital program in 2015. It expanded to the hospital’s rural satellite clinic, as well as in advocacy and community groups supported by The Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation.

It has gone beyond Africa, with Healing in Harmony programs working with Syrian refugees in Gaziantep, Turkey, and at-risk youth and refugees in Trujillo, Peru.

Darcy Ataman talks about the track “Little Bird,” written and performed by survivors of sexual violence from around the world—all of them Healing in Harmony participants—in collaboration with the Global Survivor Network and the Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation.

“Darcy, he means a lot to us. He means a lot to the world,” says social worker Sylvia Acan, founder and director of Golden Women Vision in Northern Uganda. The grassroots organization she founded in 2011 helps women affected by atrocities by the Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency group, as well as domestic violence. It began Healing in Harmony programs through The Dr. Denis Mukwege Foundation.

“

I am an artist. I am a survivor—a survivor who is an artist.

”

“I am an artist. I am a survivor—a survivor who is an artist,” she says proudly as she describes the song she recorded with Golden Women Vision. It’s a call for peace.

Acan has experienced unimaginable violence and trauma from the long conflict in Northern Uganda. She says she lost “all my people” in the LRA insurgence.

Her mother was abducted. Her father was killed. “The rebels came and slaughtered my sister like an animal, even in my presence. I will never forget that day,” she says. Orphaned, Acan would grow up in a displaced persons camp.

She says she’s seen the positive results from Healing in Harmony at Golden Women Vision. She credits Justin Cikuru, Make Music Matter’s lead therapist and trainer, and a former psychotherapist at Panzi Hospital, with the program’s success.

“It’s made them have life and hope in the future, because they thought there was no need for hope. There was no hope,” Acan says. “So, out of the teaching that Justin [Cikuru] gave, it made them strong and to become problem solvers in their lives.”

Cikuru says he’d never seen a therapy model like Healing in Harmony. By making personal music, they can repair distorted thinking connected to negative emotions, he says.

“Being a Congolese, we are used to music, actually, because our culture is music oriented. And when Darcy came in, he brought up something new, something special,” says Cikuru.

He’s seen tremendous, positive change in women who have begun the healing process through the program. As for Ataman, Cikuru says, “He is a person who never wants to see people suffer, a man who will do whatever he can to save life. And he cares, he really cares about those who went through trauma and I think he has a natural mission to heal.”

Ataman didn’t appreciate it until recently, but the two worlds of his psychology studies at the University of Manitoba and the charity’s mission meet with Healing in Harmony’s music therapy programs.

He has stepped back considerably from commercial producing work and is continuing to make songs that promote change. In 2019, he and Bottrill produced a charity single cover of U2’s “Sunday Bloody Sunday” with musicians from bands like Blue Rodeo and Billy Talent, who came together as Artists for Sudan.

Last July, Ataman was awarded the Meritorious Service Cross in recognition of his humanitarian work, one of Canada’s highest civilian honours.

He changes the subject when it comes to talking about accomplishments and awards. He’d rather talk about the power of music and the artists of Healing in Harmony.

“I just listened to the first album from Peru. I am genuinely blown away by how good it is, honestly,” he says, excited about the artists’ lyrical concepts and harmonies. “It’s all genuine. You know, there’s no artifice or performance whatsoever.”

That’s the payoff for him, making a difference in someone’s life by putting a lyric notebook in their hands and a microphone in front of them.

Says Ataman, “Once you go down the rabbit hole, it’s really hard to come back.”

Timeline

2006

Darcy Ataman produces the charity single “Song for Africa” with Canadian artists. A documentary of the same name follows the artists to Kenya to see the people and projects impacted.

2009

The Healing in Harmony pilot program begins with 70 youth from across Rwanda. Local educators guide interactive training and health education sessions, while local and visiting artists facilitate the creation of music, helping to break the cycle of stigma.

2010

Make Music Matter produces a second documentary and album, both entitled Rwanda: Rises Up!

2014

Make Music Matter hosts Panzi Hospital founder and director Dr. Denis Mukwege in Winnipeg for a series of events recognizing his humanitarian efforts, raising awareness and funds for the victims of extreme sexual violence at Panzi Hospital.

2015

Make Music Matter launches Healing in Harmony at Panzi Hospital’s Maison Dorcas aftercare facility. Parce Que J’ai Mal (Because I’m in Pain) is the first release by artists.

2016

Make Music Matter attends the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul to present the Healing in Harmony program to a global audience, including UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

2018

Make Music Matter partners with Warner Music Canada to launch a new record label, A4A (Artists for Artists) Records and Publishing, bringing songs written and recorded by Healing in Harmony artists to the world. Ataman pushes SOCAN (The Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada) to change its bylaws to pay royalties to people who don’t have permanent addresses, allowing Healing in Harmony artists to make modest amounts for their songs. There are nearly 30 albums available.

2019

Make Music Matter presents the Healing in Harmony program at the Sustainable Impact Hub as part of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. The same year, Healing in Harmony launches in Guinea, Turkey and Peru.

2020

As part of the Equality for Girls’ Access to Learning grant, and in collaboration with World Vision Canada with a funding agreement of $1 million from Global Affairs Canada, Healing in Harmony expands to Kasai, DRC, empowering vulnerable young women to speak out for their right to education.