Angelina McLeod

Fall 2020

This Anishinaabe activist, politician and documentary filmmaker grew up on Shoal Lake 40 First Nation reading graphic novels like Wonder Woman.

Exuding her own super strength, Angelina McLeod [BA(Adv)/16] would live through tragedy: Her sister, Amelia, disappeared after having to leave their home community for schooling; and her mother drowned navigating a dangerous crossing without road access. McLeod has since cast a camera lens on the inequity responsible.

Her latest project—studying sacred Midewiwin birch bark scrolls—is also a personal one. She hopes to transform the scrolls’ ancient pictographs into modern-day graphic novels, and uplift young people from her community in the process.

Tell me about your research.

Pictography is our form of literature from before the settlers came. I’m figuring out what the images mean in every scroll. They’re mostly ceremonies and traditional stories of how we came to be as Anishinaabe people. There’s the creation story, the Ojibwe migration story, herbal and medicinal training. They’re like visual guides. My research is a way for myself and for my community to find out where we come from.

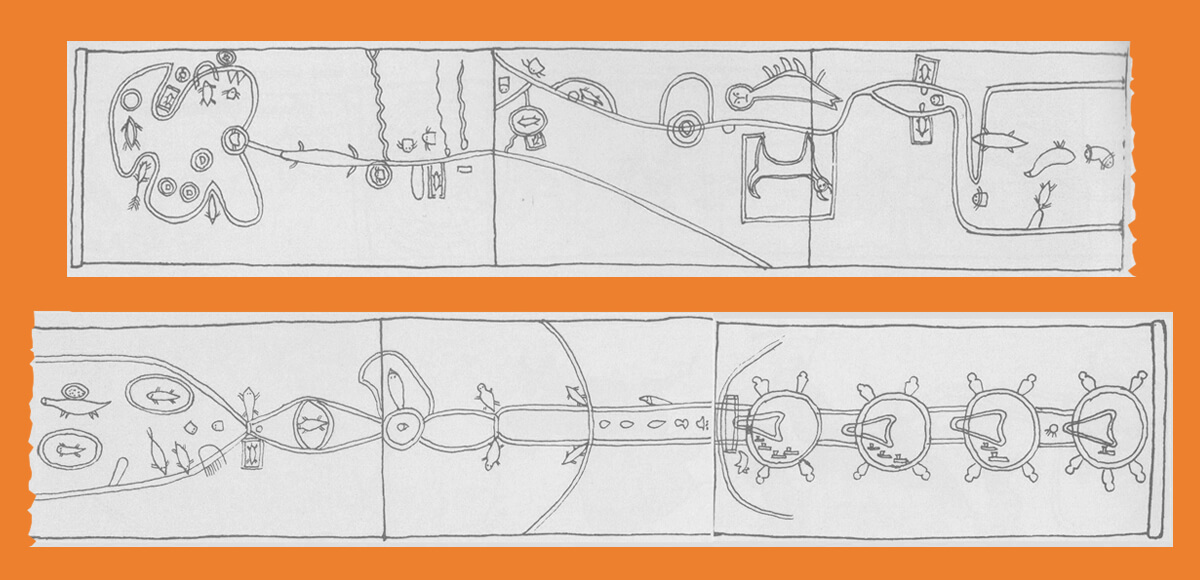

McLeod is studying Midewiwin birch-bark scrolls like this one, depicting the Creator bringing the Midewiwin good life to the Anishinaabe people. James Redsky, Birch Bark Migration Scroll (103 ft)

How long have these scrolls been around?

They say they have been made since time immemorial. Every time they would get old, they would be redrawn.

What made you want to do graphic novels?

I’m really into Marvel and DC and envisioning what super powers would look like. When I look at the scrolls, that’s what I envision. But it’s important to note, these are not fiction. They are real stories. They are very sacred, living beings, some so sacred I won’t share them all.

What led you to this?

I feel like the Creator guided me to do this work. Niigaan Sinclair gave me a book called Great Leader of the Ojibwe, and then I started reading about our history. I found out that my ancestors were powerful people—powerful Midewiwin healers. That really inspired me, so I figured if stories like that had inspired me, they would probably inspire youth in the community. These are genuine stories that need to be told so they’re not lost.

What inspires your advocacy?

I did it for my people and for my children. I lost my sister when she was 14 and I was nine, because she was sent away to school. She was a really kind person, and I looked up to her a lot. I lost my mom as well. I didn’t want anybody else to go through what my family went through and those losses made me feel like I needed to make a change.

You and your sister had to leave your community for high school. What was that transition and culture shock like for you, moving to Kenora?

It was very traumatizing, leaving home at 14. And experiencing the racism from other kids when you first get to school doesn’t feel good either. I wasn’t really exposed to any non-Indigenous kids at all, my whole life. And then all of a sudden, boom. I’m put into a classroom with a bunch of non-Indigenous kids, and we’re required to speak French. I lived in a boarding home and it was hard to adapt to all the different lifestyle changes and being away from my family. That was actually the first time I was told to pray at the dinner table. Everything was different.

Ryan Cooper and Charlene Moore’s 2018 film When the Children Left documents Angelina McLeod’s healing journey to honour her sister, one of the Indigenous children who was forced to leave her community for high school and went missing.

Can you tell me about the documentary When the Children Left?

It’s me reconnecting with the community. I go see the graves of my family. I talk about my experiences leaving the community at a young age. I talk about my sister. She went missing and was later found deceased. I still think about her every day. I never found out what happened to her. I probably never will.

Shoal Lake is known for its plight to secure a year-round access road, putting an end to dangerous routes in and out. You documented this in the Freedom Road series for the National Film Board. On the one-year anniversary of the road’s opening, how have things changed?

We don’t have to rely on the barge anymore, which would frequently break down. Now people can make their medical appointments or get groceries without worrying. We can better handle emergencies as well. No one has to risk their life anymore during ice freeze up and break-up.

What are your priorities today?

One of my main hopes is for a school that goes up to Grade 12, so kids don’t have to make the hard choice of whether or not to leave the community. And for the water and sewage plant to be finished. It’s now under construction but we’ve had a boil-water advisory for more than two decades. And I also hope for everyone in the community to have safe housing.

What are some of your childhood memories growing up there?

Being by the lake, spending time with family. Fishing, swimming, playing hide-and-go-seek, playing baseball. But there were hardships, like going across the ice in winter when it was freezing and during the spring thaw. I fell through once. It used to be nothing for me to walk on the ice, but now I’m terrified.

I grew up with no running water. We used to haul pails of water up to the house. We lived in a small, two-bedroom house with my four siblings and my parents.

Can you tell me about your role as a band councillor?

I was elected this past March, and I now hold the education portfolio for the band. It’s been pretty stressful. I didn’t expect the pandemic when I was running. Right away, we had to go into emergency mode. I’ve been going ever since.

The community is on lockdown. There are only a few people allowed in and out. We hired a safety and health coordinator, and we have a nurse helping us with our planning.

It’s not your average reservation. Everybody comes together when there’s something happening in the community. During this pandemic right now, everybody is helping out.

If you had the world’s attention for one minute, what would you say?

I would say that First Nations communities still have no clean drinking water and live in third-world conditions while Winnipeg continues to benefit from my community’s hardship. And we would like to be treated equally, just like everybody else.