Making an Impression

Spring 2021

There’s a genuine humility to Luther Konadu. He’s quick to acknowledge the artistic shoulders on which he stands, while resisting the idea that his own photography is especially unique. He downplays his position as founder and editor-in-chief of the online cultural forum Public Parking. In his short bio on Akimblog, where he contributes art reviews, he says that one of his goals in life is to “never be an art brat.”

Remarkable, considering that, at just 28 years old, Konadu [BFA/19] has already received four national photography awards. In 2019, he won a New Generation Photography Award from the National Gallery of Canada, where his work was exhibited for six months. That year, he also won the Salt Spring Art Prize for his portraiture titled Figure as Index (see below) and the National BMO 1st Art! Competition. In 2020, Konadu received the Sobey Art Award, Canada’s most prestigious contemporary art prize.

His work has been exhibited in Manhattan’s storied Aperture Gallery and Brooklyn’s Red Hook Labs. In 2019 he was hired by The New Yorker to photograph American avant-pop musician Helado Negro. He’s been profiled on CNN and was recently a finalist of Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam’s 13th Foam Talent Call. In early 2020, he had a solo exhibit at Chicago’s Filter Photo gallery.

No doubt about it—the art world is buzzing about Konadu. His trademark style, with its green tape and post-it notes, has become well-known and instantly recognizable.

Born in Canada to Ghanaian parents, Konadu grew up between the Toronto suburb of North York, Ghana’s capital city Accra, and the suburbs of Chicago. His creative parents encouraged him when he “dressed a certain way, lay the dinner table in an unusual way, or decorated the bedroom to reflect what was aesthetically interesting.” As a child, Konadu made drawings, paintings and collages, and provided sketches for his father, who was a tailor.

After high school, he attended Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, where he began to explore photography as an artistic pursuit. In 2015 he moved to Winnipeg for university.

We caught up with Konadu to talk about his approach to photography, his commitment to building community through art, and how his time at the University of Manitoba influenced his creative process.

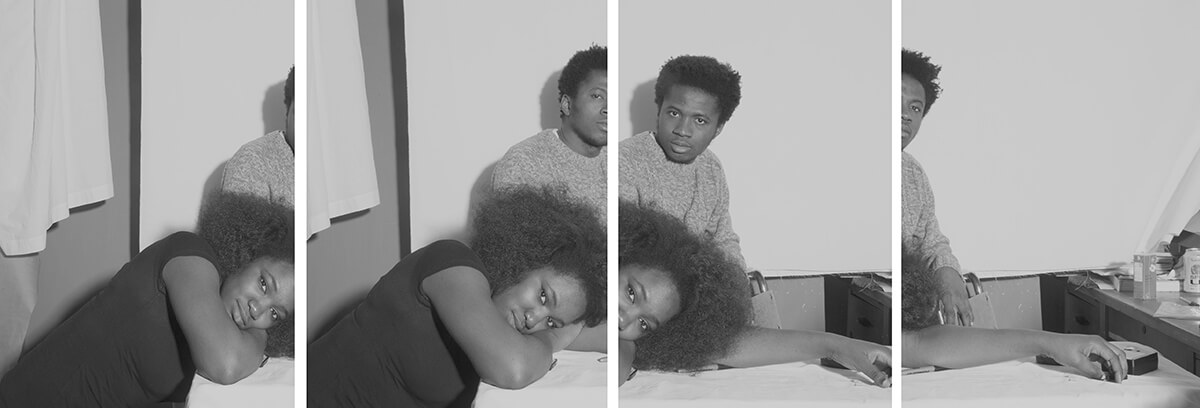

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2019 (diptych)

Why did you choose to pursue photography? What is the draw for you?

Everywhere we turn today we are surrounded by images. They’re in our homes, on our TVs, in our grocery flyers, in our books, in our emails, in our newsfeed, on our highways and, of course, all over our social media platforms—it’s really unavoidable. And so, how does living in an image world impact how we understand the world itself, if a huge part of it is seen as pictures instead of the experience of it?

That’s a starting point for me: In what ways do images shape our conception of the realities we live and feel through, and do they also affect decisions we make? How much do we really know about someone if all we have are a series of images?

I’m interested in how images can have authority over our thinking and what we come to hold as a firm belief. The world isn’t going to get any less imagistic and if that’s the case, how does that influence the way we see?

It becomes crucial to think critically about the power of an image and how it functions in our own cognition. These questions and lines of thinking are what engages me in the medium of photography.

Who are your subjects?

I always say that even though there are individuals—myself and friends within the African diaspora—featured in my photographs, the ‘subject’ for my work is photography itself and its relationship with portraiture. The people in the work are part of this subject.

I’m interested in how images have historically and, to this day, continue to be used to identify, profile, speculate about or define the lives of the individuals, communities and places they portray.

Because of an image’s strong evidential qualities, it is so easy to see a picture of someone, or of a people, and slowly formulate a resolved opinion about who you’re seeing or who they are as people—long before you ever come into actual encounter with them. Often, the power of the image becomes unshakable in the mind even after that encounter.

Art critic Antwaun Sargent said this about your work: “His subjects are looked at, but they look back, too.” Why is that important?

The individuals in my images often have a direct gaze at the camera and, in a way, it signals their participation in the construction of the image. They are aware of the frame of the camera. They are aware of their image being photographed and they present themselves for the very event of being imaged.

I wanted to give them that degree of agency in their involvement with the photograph. And I think that agency and empowerment emanates when the photograph meets the eyes of viewers.

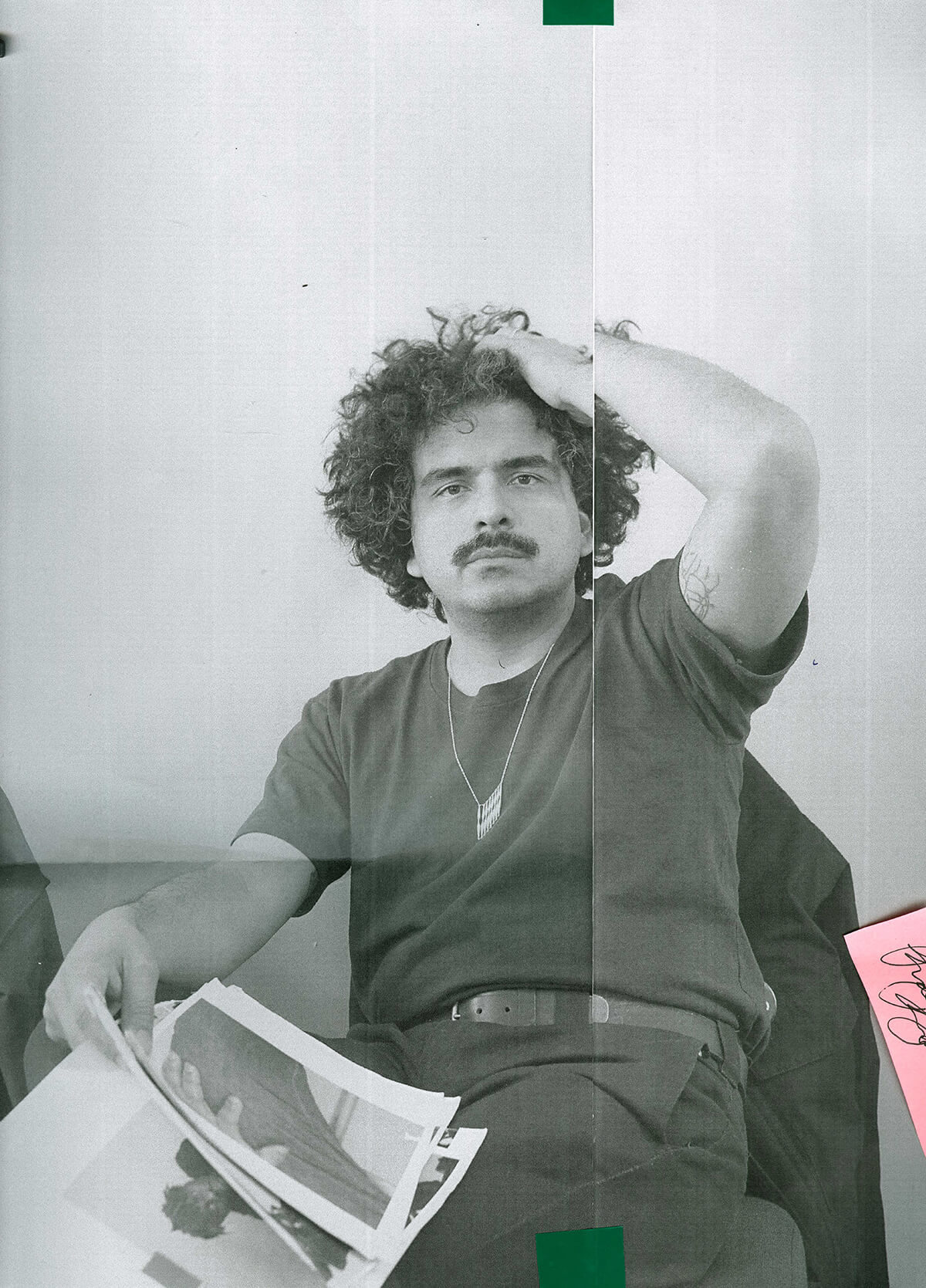

Luther Konadu, Helado Negro, Photo Illustration for the New Yorker, 2019

What was it like photographing Helado Negro for the The New Yorker?

This is one of my favourite things I’ve done so far in my life—getting the opportunity to photograph Helado Negro for The New Yorker magazine. It was crazy to say the least…. They flew me out to Vancouver and I photographed him at the venue he had been prepping in before his concert later that day.

The photo editors…gave me the creative freedom to make the image to accompany their article. They knew how I already worked and they wanted me to work in that ilk for the piece so there wasn’t as much pressure. I had versions of the final piece I sent in and they selected one for the feature.

Tell me more about your project Public Parking and its relationship to your photography work.

It is a publication that launched in 2016—while I was still at the U of M—with the intention of having critical conversations within the arts and beyond. It is a platform that has grown to house a variety of literature surrounding what artists and other thinkers are doing and imagining in contemporary visual culture today.

I started off journaling the long-winded conversations I was having with peers in the arts and it slowly branched out to include other cultural practitioners outside of Winnipeg who I was interested in. I’d cold email artists hoping they’d give me their time and engage in a conversation with me. That has since progressed further to include several artists and thinkers from across North America and Europe.

Writing and discussing contemporary visual culture through text is important not only for the context it allows, but it has the potential to be an educational tool for future use. Public Parking allows me to stay out of a hermetic artistic practice and instead find intersections with other cultural practitioners. Like my own photography work, it’s a way of building and engaging in community with others.

I understand you’re involved with youth programming for Winnipeg’s Plug-In Institute of Contemporary Art. What kind of advice do you share with young artists and how do you encourage them?

Working as an arts youth outreach person, who helps crack open the door to the world of contemporary art for individuals who don’t have the first idea of that world, is thrilling and motivating.

The program I facilitate is a mix of history-sharing that stems from the current exhibition on display, along with hands-on studio activities. I give them homework to discover new artists and read about their practices. We have discussions and they share their thoughts. I try not to overwhelm them with information but they’re often eager to know more. Once they know one artist, they become more curious and want to find out more. They pick up what I share really fast…. It feels effortless.

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2016 (polyptych)

In what ways has the experience of attending the University of Manitoba influenced your work?

I think having had access to studio space and equipment as a student to freely try things out and learn as I went along was a significant building block for me…. The program is multi-disciplinary so you get to try your hand at a bit of everything. And that structure in itself encourages a useful creative possibility out of students…. I took several classes, among which included anything from ceramics to drawing, video art, new media, graphic design and performance art.

The very fact that you are working with material or medium that you are not used to pushes you to think hard and creatively about how to produce something that is possibly interesting.

It’s been a challenging time for many. How has COVID-19 affected you? What have you learned?

I had exhibitions and photography festivals I was slated to participate in but they got canceled. Luckily, that’s about the extent of how I was affected.

Apart from mild levels of creative block coupled with a sense of diminished motivation for most things, I’m better than most.

We are still moving through the pandemic and I don’t know if I’ve really processed it enough to know what I’ve learnt. I guess one thing is for sure: uncertainty looks to be an ongoing constant.

And in terms of what’s next, tentatively, I have some exhibitions lined up for the year in Montreal, Amsterdam, Regina and a residency in Salt Spring, B.C., but that’s about it for me.

Luther Konadu, Figure as Index, 2020

Anatomy of a Photograph

We asked Luther Konadu to walk us through the making of one of his works:

This is an amalgam of images taken at different points in time over the last five years and they are all brought together into this single picture plane—so you are looking at different timelines collapsing into one. Your eyes are displaced in multiple directions and it is not focused necessarily on a singular point of view. I like to think of it as an extended self-portrait that includes my community of friends. You see me with a camera in the middle of capturing an image, and you also see me in the middle of composing the image you are looking at, with my hand coming from the corner. Most of my images are fragmented in that way and indicate the construction of the photograph you are looking at.

There’s also a text that says “VIEWING,” which points back to the very activity viewers are engaging in when they see my work. It is a way of making you aware of yourself and what you are doing as you are doing it. We easily get lost in images and their allure to provide seamless insights into the world they are showing us. And so these self-referential elements are to reinforce what you are looking at as just a surface or the artifice of something broader that lives off the edges of the printed images taped together.

All of this is further consolidated by scanning it. So what you are really seeing is a picture of several pictures all scanned together into one flat image space. This, I believe, speaks to the way photos work in general; they take the fullness of an experience or event and compress all of that into the flatness of a single surface, and a lot is always left out in this way of representation. I should add here that the piece is called Figure as Index, meaning those imaged—the individuals, including myself—appear as an index or, in other words, a mere trace.