An Awakening

Fall 2020

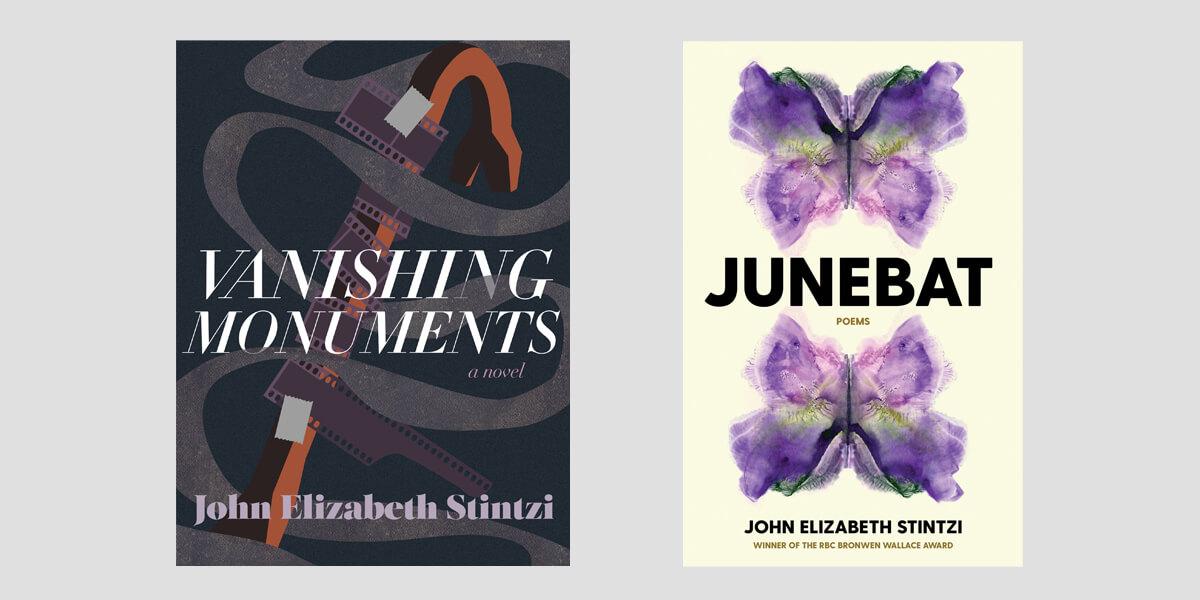

John Elizabeth Stintzi [BA(Hons)/14] realized who they are through writing—the Kansas City-based author started identifying as non-binary (and using pronouns they/them) while creating a character for their novel Vanishing Monuments. The release, which landed a spot on the Toronto Star’s list of 20 books to know about, sees the main character wrestle with their estranged mother’s dementia.

Stintzi documents some of their own reckoning in another book, Junebat, a volume of identity-themed poetry. That too earned accolades: selections from Junebat won the 2019 RBC Bronwen Wallace Award for Emerging Writers (unfortunately Stintzi’s family couldn’t attend the award ceremony—it was calving season).

The 29-year-old artist talks to us about finding peace within inconclusion, the paradox of the Hamptons, and their non-binary cactus named Hale-Bopp.

How did you first discover writing?

I’ve always been creative, and my family has always been very creative. My mom was a writer and a journalist. We lived on a farm, and there was nothing to do, so we had to make up stories all the time and play make-believe a lot.

I started writing really bad poetry when I was a junior in high school. That was when I latched onto it, like “Oh, this is the thing I can express myself in.” I also had a few people who read it and said that I was good so I just continued, even though my poems were God-awful.

You grew up on a cattle ranch in northwestern Ontario. What was that like, as an LGBTQ teen in a small, rural community?

I mean, I really had no idea what was going on. I barely even knew that gay people existed.

But growing up on the farm, it didn’t seem to be important—the gender stuff. I was just one of the kids. We all played with Legos until we were, like, 17. My parents weren’t trying to police how we acted. “Oh, you’ve got to man up”—there was nothing like that.

So you discovered your identity much later?

When I was in university I did an English degree, but I somehow avoided all of the queer-theory aspects. The next three or four years was the process of learning more about queer people and LGBTQ people—through writing Vanishing Monuments, honestly. Because I wrote this non-binary character and then had to, through revision and revision, learn more about them, whittling it down to the point where suddenly the differences between them and me seemed much less stark.

I was like, “Alright, this is what I am. I figured this out, and now I have to live with the fact that I figured this out.”

Where does your middle name, Elizabeth, come from?

A friend of mine just started calling me John Elizabeth, and I liked the sound of it. And then eventually, I was getting into being clearer about my identity. I don’t hate John, but I wanted to have an easier flag that you should look at my bio before you use a pronoun for me. It’s also my mom’s middle name. It’s sort of pseudonym-ish. It’s not my legal name or anything—maybe one day.

What’s the biggest misconception you face as a non-binary person?

Mostly that it’s so interesting. I don’t think it’s interesting or very exciting. It’s just a fact about me. It’s not the thing that defines me. It’s been a flash in the pan of my life that I’ve even understood this thing about myself, right? The thing that defines me are all these interests and concerns and these ideas I have about identity as a whole.

Can you tell me about them?

I’m interested in fluidity and the ways in which identity is mutable. I feel unconvinced that it’s this static thing. I’m a different person speaking to you on the phone than I am to my dog [a Patterdale terrier named Grendel.] In between those social interactions, there are these ways in which who you are is renegotiated. Gender is one specific aspect of that, but also memory and all these other things come into play.

Like, Vanishing Monuments is a novel mostly about memory and the instability of identity, because the mother has dementia. How does that change who she is? She’s not able to remember all of these things or even recognize her own child. How does that change this mother-child relationship?

I also think it’s a lie that you have to know who you are—that you have to have a clean-cut idea of yourself—in order to be real. That’s a weird myth. There’s so much about me that I don’t understand, and it’s sort of exciting and interesting to just know and be okay with that.

Tell me more about the inspiration behind Vanishing Moments. Do you have a personal connection to dementia?

It’s a novel about a non-binary photographer and teacher who returns home for the first time in about 30 years—the home being Winnipeg—because their mother, who’s been suffering from dementia for the last decade-ish, has suddenly lost the ability to speak. It’s sort of about trying to come to terms with things and trying to make peace with someone who is more or less uncommunicative.

I was taking a class on collective memory. There’s this monument which is called the Monument Against Fascism, which was in Hamburg, Germany. And it’s this big, lead-skinned, obelisk-looking monument. There were metal styluses, and you were supposed to write your name on it to pledge yourself against fascism.

But only so much of it was in reach. Once that was filled up, they would lower it into the ground, and people would write on that part of it. And then they would lower it further into the ground. Eventually, it was just underground. So it was this interesting vanishing monument. I was so excited thinking about the mortality of memory. It just was really rich to me, and it led me towards this novel.

There are certain inspirations that were derived from my life. Some of the stuff with the mother is related to my grandfather fading away near the end of his life and losing his memory. When he died, I felt like a version of myself was suddenly gone.

Tell me about Junebat and where those ideas came from.

Junebat is set during 2016 to 2017. I had just finished coursework in my master of fine arts and moved to Jersey City. Part of the appeal of that was to unpack all these feelings that I’d been having. I’d been having a really bad year, and I just was like, “I need to go somewhere and figure out what’s wrong with me.” I really came to terms with my queerness and decided what that meant to me.

The junebat is something that I created—it’s not a real thing. If you Google it, you just get stuff about me. But it’s this figure that shows up throughout the poems which is this contradictory, fluid, identity-ish thing. Sometimes it’s very combative, and sometimes it’s very tender. It’s meant to embody instability or “unknowable-ness.”

We asked Stintzi to again be consumed by ideas around identity and produce a self portrait.

What do you want people to take away from reading your work?

The thing about both these books is just the idea of inconclusion and how you have to be okay with it. Like, you read Junebat, and you’re like, “I’m gonna figure out what a junebat is by the end of this,” and you don’t really get to know. And with Vanishing Monuments, we don’t really get a lot of resolution. It’s sort of like life—sometimes you just don’t get to know.

Can you share a line of poetry you’re particularly proud of?

One line that I’m always excited to get to when I’m doing a reading is from my poem “Hale-Bopp.” The poem is talking about this cactus that I had and how I sort of made them into this queer character in my life. Like, I gave my cactus (whose name was Hale-Bopp) they/them pronouns. My queer thing in my house was this little cactus. Eventually, somewhat by neglect, the cactus died.

This line really spoke to me, beyond this particular poem: Poetry is where I go to be powerless.

It’s where I think some of my other poems also come from—these moments of powerlessness. It’s the place where I go to fail at saying something. I don’t think a poem is successful unless I fail to really capture what I was trying to capture. If I get everything down, it feels like it’s dead and preserved in a way that’s not interesting.

So, you’re saying you only succeed if you fail at articulating your poetic intention?

I feel like if you get something exactly right, you sort of kill it. It’s sort of a clinical, “Okay, I’ve addressed every single thing.” And there it is, splayed out or vivisected or whatever. “There you go.” There’s no room for the reader to do any work.

If I don’t get everything, I can go back and read that poem, and it still feels alive and present to me. There’s more work in terms of the reader pondering.

Obviously, there’s a lot of beautiful poetry that is very clear and finished, and I think there’s definitely a space for that. The idea of control comes into it. It’s weird to have a story or a piece so controlled in a world where we have so little control. It feels totally weird to me.

You lived in a curious part of Long Island, N.Y., while doing your master of fine arts. What do the Hamptons mean to you?

It’s a very weird place. It’s very much a tourist town, but it gets pretty deserted after Labour Day. I feel like I learned a lot about my love for the ocean. I’d never seen anything bigger than Lake of the Woods in my life.

It’s also a deeply complicated place. There’s so much money. There are $30-million or $10-million houses sitting on the beach that are stayed in maybe three weeks a year or something —or generously, maybe three or four months—and then otherwise are just completely unoccupied. There are no streetlights, because everyone in the Hamptons wants to be able to see the stars at night. But there are also a lot of immigrant workers who are riding bikes in the middle of the night down the street. That’s who has to work for these people.

How has the pandemic impacted you?

It has affected the marketing of my books a lot. I had a tour set up. I think I was supposed to be in Edmonton right now. I had 10 to 12 events that I was supposed to be doing during our launch.

It really brought me back to being like, “Okay, the thing I have to focus on is writing. I can’t be focusing on this other stuff beyond my control.” I grieve about it every now and again, but I also know that these books aren’t going to go anywhere. Even if they don’t do as well as I want them to now, when I publish the next book, people will be like, “I like this book. Has this person written anything else?”

Pick a title right now from your bookshelf and tell me why you like it.

I have a copy of Simon Armitage’s translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which is a medieval epic. There’s this big ball and this green knight shows up. He’s completely green—his armour’s green, his horse is green. He’s just like, “I want someone to trade blows with me. You can hit me once, and then a year later, I get to hit you.” Sir Gawain is like, “I’ll do it.”

So he cuts off the green knight’s head with his axe, and then the green knight picks up his head. And he’s just like, “See you in a year,” and then drives off. I don’t know. It’s been a while since I read it, but it’s very weird.

Favourite UM professor:

Struan Sinclair, associate professor in English, Theatre, Film & Media. “He is one of those people who’s so intensely passionate about what he does. I was so lucky to get a professor who was so obsessed with writing and with language.”

UM memories that are top of mind:

Running through the tunnels mid-winter, eating poutine at Degrees, going to class to hear someone talk about Chaucer for an hour. “It’s the everyday things that I really miss.”

A go-to dinner party anecdote:

“A friend and I were camping and our campsite was visited several times by this bear who only had three legs: Three-paws.”

Topics of the first two poems published:

A cow who escaped and lived in the woods. An elegy to Irish poet Seamus Heaney.

Number one on their bucket list:

Getting close to a volcano.

Best advice received:

“Don’t put any piece of advice on a pedestal. There’s always an exception.”