How do we protect the pristine Arctic?

Spring 2020

The Arctic contains an estimated 20 to 30 per cent of the world’s undiscovered oil, and companies seeking the financial payoff will want to drill for it. So, as our warming climate weakens or melts sea ice, the once inaccessible locale opens itself to mineral companies and becomes a new corridor for global shipping, forcing us to ask, What would happen if things went wrong in such a remote and harsh place?

At worst, if an oil spill occurred right before or during winter’s freeze-up, no emergency vessel could respond. The oil would flow until spring and the ice, always moving, would drag it throughout the Arctic’s pristine vastness.

But “development of resources is not wrong,” says David Barber [BPE/82, MNRM/89], Canada Research Chair in Arctic-System Science and associate dean of research in the Clayton H. Riddell Faculty of Environment, Earth, and Resources. “What’s wrong is to do it without any thought to sustainability and the protection of the environment. We have to put a real cost on the impacts we have on the environment, and scientific research can help with that process. That’s why we are building the Churchill Marine Observatory.”

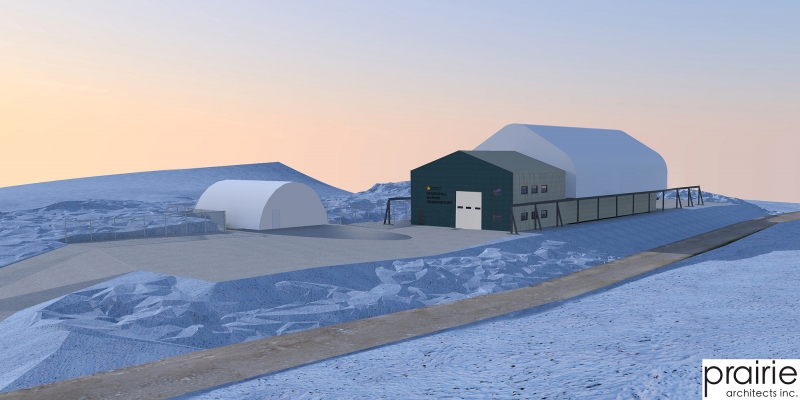

CMO, which is set to open in the summer of 2020, is a $32-million facility funded largely by the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Province of Manitoba, the latter through the Front and Centre campaign. It will be the first of its kind in the world.

Prior to CMO, 12 laboratories across the globe, including the Sea-Ice Environmental Research Facility at UM, studied homemade sea ice by adding salts to groundwater. Though fruitful, these studies lack key ingredients like native Arctic bacteria. CMO offers a laboratory in the Arctic Ocean.

The station will operate year-round on the shores of Hudson Bay, offering upwards of 20 researchers at a time access to a suite of instruments monitoring the ocean, estuary and air, as well as the main attraction—two pools filled with seawater. Finally, UM researchers and their partners at the University of Calgary, University of Victoria, Dalhousie University and Université Laval—along with other international players, including governments and private companies—will be able to run controlled experiments and gain unprecedented insight into the Arctic ecosystem and how we can protect it on that inevitable day when oil spills from a supertanker or rig.

Just how will contaminants interact with not only the Arctic water but the staggering complexity of sea ice, full of channels and microscopic life? We’ll soon know.