360°

Fall 2019

Climate change comes at us from all angles and requires an equally robust response. These UM alumni—who are taking action and leading conversations in their field—talk blue jeans, juicy hamburgers and businesses going under (along with the planet).

SLOW IT DOWN

In fast fashion, brands create cheap, trendy clothing at lightning speed—think Forever 21 or H&M. From the design to the retail racks, they have a turn-around of five weeks or less.

Katherine Magne [BA/03] used to have her credit cards memorized to fuel her addiction.

“I was 100 per cent that person who was like: I’m not paying $15 for that blazer. I need it for 10,” says Magne, 39.

She didn’t realize churning out products has some serious environmental consequences. Making a single pair of jeans, according to the World Wildlife Foundation, requires 1,800 gallons of water to grow and dye the cotton. And one cheaply constructed polyester blouse sends tiny pieces of plastic into the waterways with every wash. Magne went on a one-year shopping ban—and never looked back. She started to sew, using more sustainable fabrics like Tencel (with fibres made from the Eucalyptus plant) and five years later, holds monthly sewing workshops for like-minded Winnipeggers reimagining the old patterns their grandma once used. This year, Magne co-led the city’s inaugural Fashion Revolution Week to educate other aspiring makers.

She admits fast fashion is a powerful force. It’s been 25 years since NAFTA removed barriers to trade, making the outsourcing of cheap labour and materials a new norm. “I feel rich because I can go buy three T-shirts for $5. It’s feeding into this cultural schism that’s happening right now: I know I shouldn’t. But it’s so easy for me to just go and buy this. And then I get that rush of belonging.”

The entrepreneurial mom, who sews 99 per cent of her own clothes or buys second-hand for her four kids (ages four to 10), believes there’s something to be said for taking a stand against instant gratification. “The little one—she doesn’t even really know that clothes come from stores. In her eyes, clothes are made by a person, and that person is mom.”

Get Up to Speed

- Find new ways to style your current wardrobe so you keep clothes for their full life span. If a sweater has a snag, fix it. “The most sustainable clothes are the items you already own,” says Magne. “Selling sustainability isn’t sexy. Because sexy is so highly regarded, right? But like, do you have to make it sexy?”

- Check out the Cora laundry ball—a Kickstarter success you throw in the wash to catch micro-plastics from synthetic fabrics.

- Read Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion by Elizabeth L. Cline.

- Beware of “greenwashing.” “A brand just uses buzzwords to create a sustainable capsule collection. Look at us, we’re being so sustainable. When 90 per cent of the rest of your stuff is still unsustainable.”

WHERE’S THE BEEF?

Everyone loves a good Big Mac, even food scientist Filiz Koksel [PhD/15].

The North American hamburger brings comfort. It’s familiar, tasty and easy to eat. But with a great burger comes great environmental impact: Reports show for every quarter-pound beef patty, 6.5 pounds of greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere.

Given how plant proteins require less water and land to grow—unlike methane-producing cows—Koksel is on a mission to make a better plant-based burger.

The key is to accurately mimic the juicy and fibrous texture of meat (some food suppliers even replicate the blood with beet juice.) This assistant professor, in the Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, and her team are the first in the world to use ultrasound to analyze what exactly’s happening to ingredients like wheat gluten, pea protein and soy protein while in the extruder: a machine that mixes, cooks, and shapes foods all in one. They’re characterizing the hardiness and chewiness, as well as nutritional properties, like protein digestibility and amino acid composition.

“When different components of foods—like proteins, carbohydrates and air cells—come across ultrasound waves, they dance to different beats with the incoming ultrasonic music,” says Koksel. By recording these beats, we can extract information on food structure and texture.”

The target audience for these pseudo burgers? Mostly “flexitarians”—those who eat a primarily plant-based diet, but still enjoy meat occasionally, says Koksel. She identifies as one herself.

WHY AREN’T WE DOING ANYTHING?

As adults, we make about 35,000 decisions a day. We need guidance—or nudges—to make choices in our best interest. That’s why behavioural economists like Hersh Shefrin [BSc(Hons)/70] step in.

He knows people can be unpredictable, impulsive and foolish. And he knows how these human conditions have had disastrous consequences for financial markets and the state of our planet. It’s a topic he regularly writes about for Forbes, HuffPost and The Wall Street Journal.

We listened in as Shefrin, the recipient of the 2019 Distinguished Alumni Award for Lifetime Achievement, spoke to a roomful of babyboomers at a Seniors’ Alumni Learning for Life event on campus. Here’s his take…

On the carbon tax: Economics is what’s driving climate change. A carbon tax is the only major policy we know of that’s required to get the job done if we’re serious about keeping climate change at manageable levels—everything else is small fry stuff. But it’s not happening globally and we need to understand, why the resistance?

One reason is poor people are going to have to pay a high price today to reduce carbon—but the benefits mostly flow to future generations. And life is already tough for poor people. In democratic societies, poor people can express themselves through the ballot box. Politicians pay attention.

People associate only negativity with something called a tax. Proponents should shift focus to the benefits: climate change policies that will help the planet, improve health and create more jobs. It feels less like a loss if it’s packaged with sweeteners.

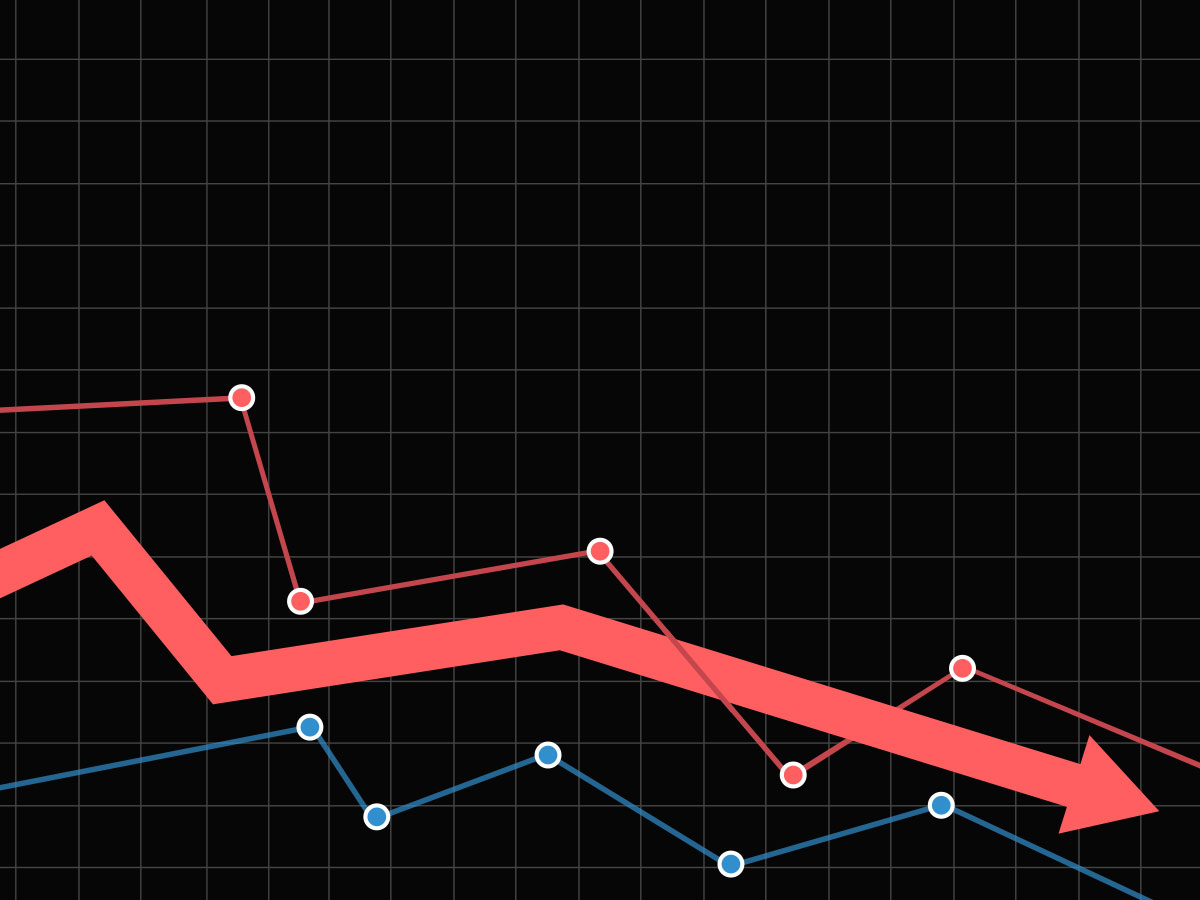

On the new business reality: In California, fire season starts earlier now. It ends later. A day might start out just fine and then—10 minutes from now—there’s a fire. And it’s moving so quickly, if you’re not out in 30 minutes, you’re toast. The damages have been enormous.

Growing up, Manitoba Hydro provided the electricity to my home on Inkster Boulevard. Now that I live in California, it’s Pacific Gas & Electric. They recently declared bankruptcy because their generators sparked major fires in California that left them with legal liabilities too large for their asset base. PG&E became the world’s very first climate change bankruptcy for a major organization. And more are likely to come.

Europe is developing a system that requires publicly traded companies to disclose, not just their financial statements, but their climate risk exposures. That’s going to be a normal part of business culture. Suppose you manage a pharmaceutical firm and have a manufacturing operation, say in Puerto Rico. Now say there’s a major hurricane there. You might not be able to recover from such a disruption to supply. Climate change risk management will need to become front and centre.

On the coming shift: Climate change is going to generate major human migrations. People who live in areas that become permanently flooded, or ravaged by drought, are going to look for nice places to live. Don’t be surprised if the Canadian North, several decades from now, begins to look good. Siberia too. As far as I can tell, Vladimir Putin’s policies do not help fight climate change, possibly because Russia looks to be a beneficiary. Since northern Canada looks to be a beneficiary, this suggests Canadians are going to have to start worrying about having a stronger military, because of territorial disputes. Don’t be surprised if these kinds of challenges come up in future years.