What Will Vaccines of the Future Look Like?

When COVID-19 swept the globe, hospitals filled and supply chains broke down. Canada waited months for doses to arrive from abroad, exposing how unprepared we were.

Now scientists are rethinking what vaccines could be—faster to make, easier to deliver and designed to meet the next global threat head-on.

We asked Peter Pelka, a professor in the Department of Microbiology at UM: What will vaccines of the future look like?

Made in 100 days

Traditionally, vaccines took years to develop, which is far too slow for viruses that can spread worldwide in weeks. COVID-19 proved it doesn’t have to be that way, with vaccines created in the U.S. at record speed, yet Canada couldn’t produce them at all.

Pelka wants to change that. His team is working to develop a flexible platform that could turn an emerging virus threat into a vaccine in as little as 100 days.

“The objective is to develop a platform so that no matter what pathogen comes around, whether it is a pandemic virus or a disease with pandemic potential, we can have it in vaccine form within about 100 days,” Pelka says. “It would be ready to deploy in a similar way to the seasonal flu shot, using a platform that is safe and well understood.”

The difference this time? Investment and scale.

Backed by a $57-million federal commitment, UM is building the Prairie Biologics Accelerator at its Fort Garry campus and the PRAIRIE One Health Emerging Respiratory Disease Centre at its Bannatyne campus. These facilities will anchor a Prairie-wide biomanufacturing hub that links UM with researchers at the Universities of Alberta, Calgary and Saskatchewan, creating the capacity to design, test and manufacture vaccines right here at home.

“COVID-19 exposed the fact that we had no capacity to manufacture a vaccine in-house,” Pelka says. “It was immediately recognized that we couldn’t prioritize our own citizens. We don’t want to be in that position again.”

Peter Pelka, a professor in the Department of Microbiology at UM

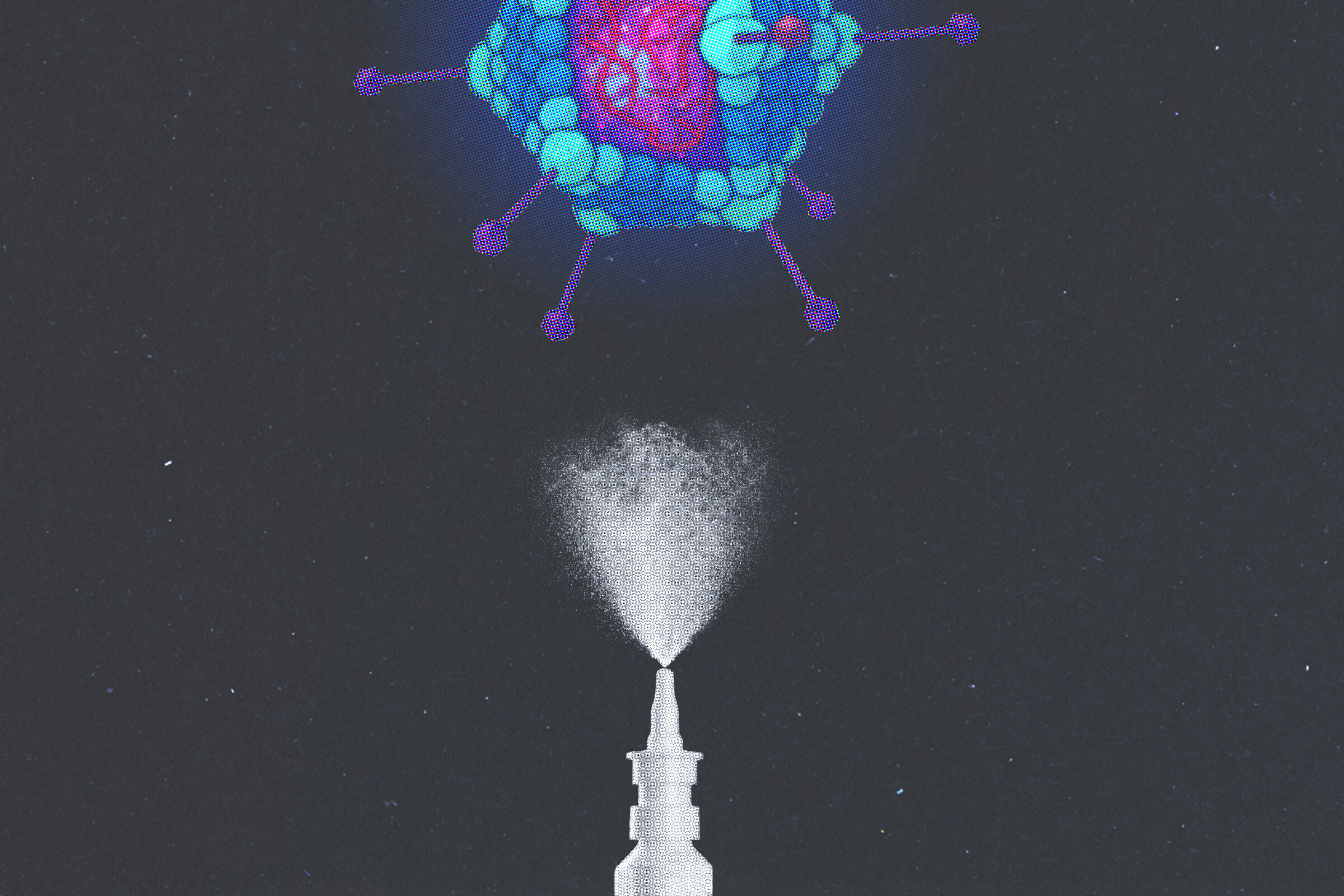

Needle-free delivery

The vaccines most people know come in a syringe. But Pelka believes the future will look different. His team is working on vaccines that can be taken orally or through a simple nasal spray.

“Delivery by oral route and nasal is not something new. Polio vaccine, for example, is still given this way,” Pelka says. “What excites me about this is that it will reduce barriers, it will reduce the cost, and I think it will increase uptake of the vaccine.”

One of the biggest barriers is access. Some communities don’t have a doctor, nurse or pharmacist to give injections, and some people are reluctant to get injections at all. Needle-free vaccines, which could be used at home, remove those obstacles.

Also, Pelka says the needle-free vaccines could be stored for weeks or months without special equipment. This makes them easier to distribute and use in communities with limited health-care access.

And by targeting the nose and mouth—the same places where many pathogens enter the body—these vaccines may also provide stronger protection at the site of infection.

Smarter design

One of the biggest hurdles in vaccine development is the sheer amount of data generated in animal studies. Hundreds of different immune responses can be measured, but only a few actually predict whether a vaccine will work.

Pelka and his colleagues are using artificial intelligence to cut through that noise. By training algorithms on large datasets, they can identify which signals matter most—and ignore the rest.

“That way, the next time we develop a vaccine, we don’t need to repeat every test,” Pelka says. “We can focus on the predictors that really matter and not waste time or money on the rest.”

In practice, this means moving from trial and error to targeted design, shaving weeks or months off the development timeline. For Pelka, it’s a key step toward reaching the goal of a 100-day vaccine.

Building jobs, building innovation

The benefits of the Prairie Biologics Accelerator and PRAIRIE One Health Emerging Respiratory Disease Centre will extend beyond health security. Construction will generate jobs immediately, while the long-term payoff will come in research and biomanufacturing careers. Once operational, these state-of-the-art facilities will help attract top talent and create opportunities for the next generation of health-care innovators, Pelka says. Together, they add a new dimension to Manitoba’s health-care system and economy, positioning the province at the centre of vaccine innovation.

Where most people see problems, Bisons see solutions. Explore and meet UM researchers—like Peter Pelka —who are changing lives in Manitoba and beyond.

Peter Pelka is a professor in the Department of Microbiology at the University of Manitoba. He is one of the prominent researchers behind a Prairie-wide collaboration with universities across Western Canada to strengthen vaccine research and biomanufacturing. His vision is to use what we know about viruses to build faster, safer vaccines that can protect people from the next pandemic.