What Does it Take to Grow Vegetables that Fight Disease?

In a converted hall on Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN), rows of kale, cabbage and broccoli sprouts glow under red and blue LED light. Behind that glow is an effort to address the northern Manitoba community’s most pressing health challenge.

Fresh produce is scarce at OCN, where nearly half of the adult population lives with diabetes and hypertension. Miyoung Suh, a professor in the Department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences at UM, is working with the community to grow “supercharged” greens that could help.

We asked her: What does it take to grow vegetables that fight disease?

Grow smarter

In the “smart” vertical farm at OCN, Suh works with community members to grow microgreens—young veggies picked soon after they sprout—under tightly controlled conditions.

Artificial intelligence and computer systems regulate light, nutrients, water and carbon dioxide, creating an environment that pushes the plants to produce more of their natural protective compounds.

“This technology lets us grow vegetables with more nutrients than what’s usually available in the community,” Suh says.

Vegetables in the Brassica family like kale and broccoli are already known for their bioactives—natural compounds such as phenolics and glucosinolates. These compounds are linked to blood sugar control, lower inflammation and better heart health.

By adjusting how the plants grow, Suh explains, they can encourage microgreens to produce even more of these compounds. The result is food that is not only fresher but has more potential to help protect against diabetes and hypertension.

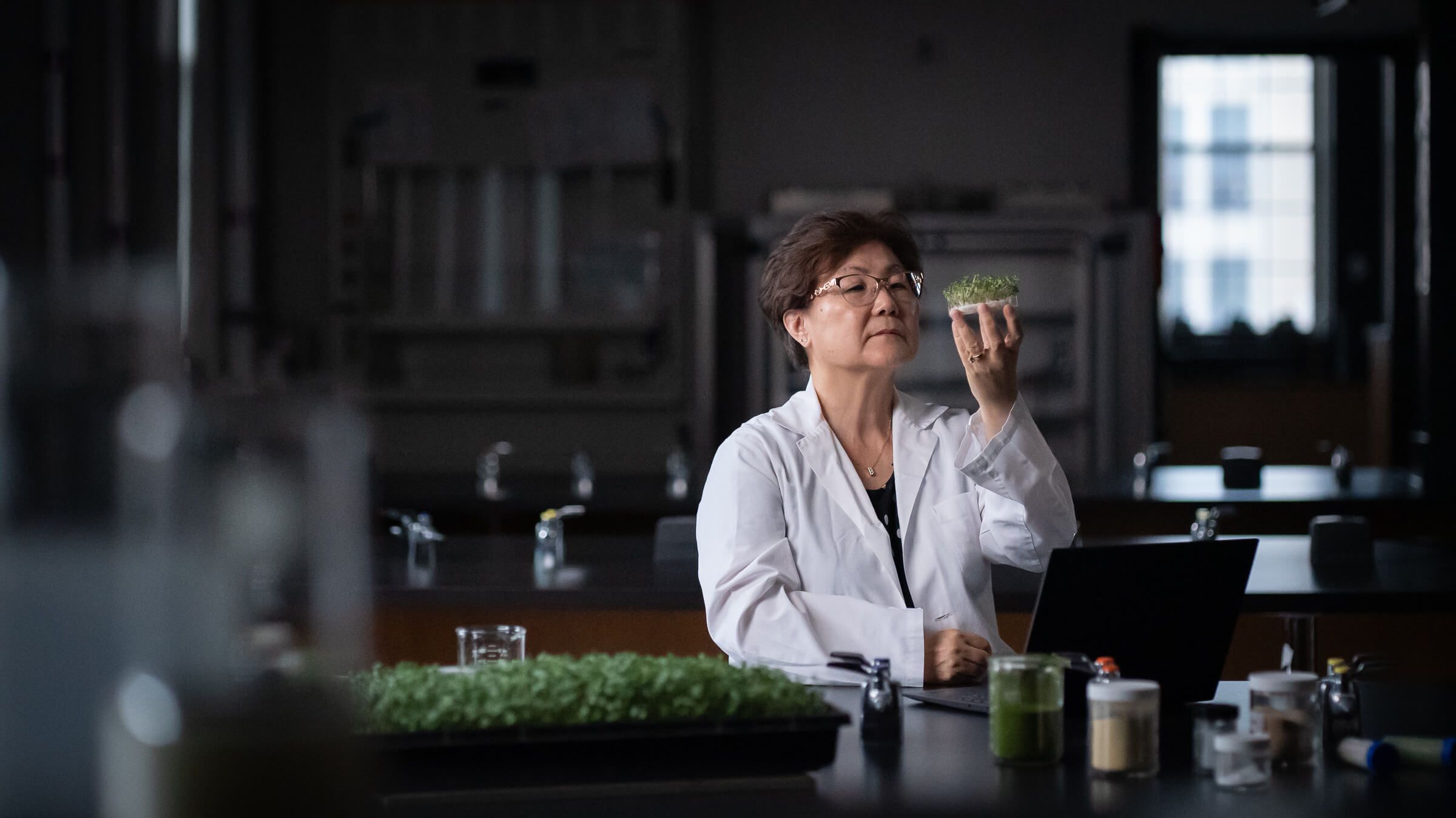

Miyoung Suh, professor of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences at UM

Evidence-based science

Back in her lab at the St. Boniface Hospital Research Centre, Suh dries and grounds the vegetables into powders so they can be tested more closely. The first step was comparing them to store-bought vegetables and to Health Canada’s nutrition tables. The OCN-grown samples consistently showed higher levels of key nutrients.

“Vegetables grown at OCN are really enriched,” Suh says.

The next step was feeding them to rats on high-fat, high-sugar diets similar to those that often lead to obesity in people. The results were striking.

“Heart function improved, blood pressure went down and body fat decreased—even when body weight didn’t change,” Suh says.

Now the team is running studies with rats that have type 2 diabetes to see if the same benefits hold true.

“As scientists, we need a complete set of data to understand how this works,” Suh says. “But what we’ve seen so far is very promising and exciting.”

Make it part of everyday food

Of course, vegetables only matter if people eat them.

At OCN, where fresh produce hasn’t been a regular part of the diet, Suh’s team is looking for ways to make the microgreens easier to embrace. That means turning them into foods the community already enjoys.

Working with chefs from Red River College’s Prairie Research Kitchen, they’ve tested recipes that add the greens into familiar dishes. A chili made with kale, for example, was handed out at OCN’s Indian Days celebration. Cornbread muffins with added kale powder were another hit.

“The people loved it,” Suh recalls. “Many of them who had never eaten kale before did not notice that the food contained about 10 per cent kale.”

It’s not about changing traditions, Suh stresses, but about adapting them.

“Even if people don’t like vegetables on their own,” Suh says, “we can carefully listen and make food they actually want to eat.”

Rooted in partnership

The project began with the community itself. OCN launched the vertical farm in 2016 and asked Suh to study its health impacts. From the start, the work has been co-designed with the OCN Health Authority, ensuring research follows community priorities.

By running the farm locally, OCN is reducing reliance on expensive southern shipments and gaining steady access to fresh produce year-round. That shift strengthens food sovereignty, giving the community control over its own supply of healthy food.

Where most people see problems, Bisons see solutions. Explore and meet UM researchers—like Miyoung Suh —who are changing lives in Manitoba and beyond.

Miyoung Suh is a professor of food and human nutritional sciences at the University of Manitoba and a principal investigator at the St. Boniface Hospital Research Centre. A registered dietitian and nutrition scientist, she is recognized for her work on lipid metabolism, diabetes and neural health, and serves as nutrition lead of the Canada Israel International Fetal Alcohol Consortium, a global initiative to reduce the impact of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

New test farm at UM poised to beat tariff threat with local produce