What Are the Risks and Opportunities of a Changing Arctic?

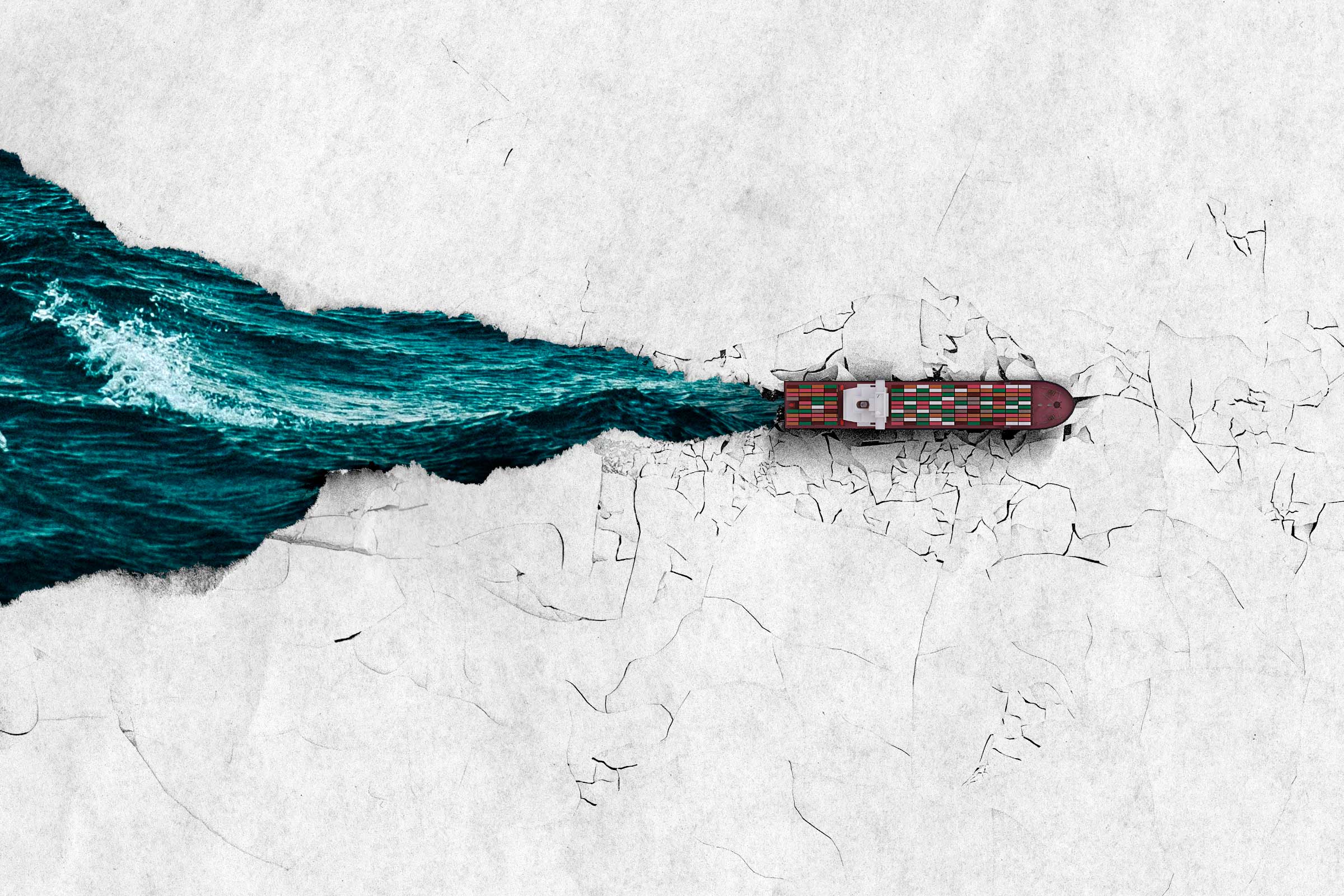

A cargo ship moves through Hudson Bay toward the Port of Churchill. For millennia, ice covered these waters most of the year. Now climate change is shortening the ice season, leaving more time for ships to pass.

For Churchill, Manitoba, this shift brings both unprecedented opportunities and enormous challenges. Warming could open the door to development that makes the town a hub for regional connectivity and global trade, but that same development could also threaten Arctic ecosystems already under stress.

We asked Feiyue Wang, Canada Research Chair in Arctic Environmental Chemistry at UM: What are the risks and opportunities of a changing Arctic?

The risks

Hudson Bay is opening up faster than anyone expected.

“Hudson Bay’s sea ice condition has changed dramatically over the last several decades,” Wang says. “From the 1980s, every year we gained on average one more day of open water. At this very moment, on average, the Bay is ice-free for about five months.”

A longer season of open water means more ships and greater potential for risks such as oil spills.

“Whenever you have shipping, there’s always a risk of an oil spill. And that’s just a given. If somebody says there’s absolutely no risk, that’s absolutely not true,” Wang says.

UM’s Churchill Marine Observatory was built to prepare for that potential reality. Its outdoor seawater pools recreate Arctic conditions so scientists can track how oil behaves in cold waters or under ice, and test technologies designed to find and mitigate spills.

In warmer waters, oil floats to the surface and spreads. When sea ice is present, oil can become trapped beneath it or encapsulated in it, hidden from view and harder to clean up.

“First of all, if there’s an oil spill in ice-covered water, do we even know whether there’s a spill?” Wang asks. “And then we want to study the impact of that oil spill and how to clean it up. We are developing new technologies that are specifically adapted to cold and icy waters so that if there is a spill, technologies are in place to mitigate.”

Oil isn’t the only concern. Climate change and increased shipping can also affect Arctic wildlife through disruptive underwater noise and the introduction of invasive species. UM researchers are studying beluga behaviour in Hudson Bay to better understand how ship traffic impacts the whales and to help shape safer routes.

Feiyue Wang, a Tier-1 Canada Research Chair in Arctic Environmental Chemistry at UM

The opportunities

Shipping through Churchill has historically been constrained to a narrow three-and-a-half-month window. That short season kept the port from reaching its potential and left northern communities with some of the highest costs of living in the country.

Now Wang and his partners are embarking on a bold initiative, exploring how a longer open-water season could change that. Working alongside Indigenous knowledge keepers and northern leaders, the goal is to improve accessibility for northern communities, strengthen food security and better connect Manitoba to global trade.

“The initiative from the very beginning was driven by community folks,” Wang says. “They wanted to see development on their terms. They recognized both the challenges and opportunities.”

The potential reaches far beyond Churchill and other Hudson Bay communities. A reimagined third seaway—east, west and now north—could link Prairie grain, minerals and other resources to markets in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas.

That’s why Wang has been calling Manitoba a maritime province, an idea once met with laughter but now gaining traction in policy circles.

Wang is clear that development in the North is no longer a question of if, but how.

“It has to be economically viable, but it has to be culturally sensitive and appropriate and environmentally sustainable,” he says.

That balance means learning from past mistakes. Canada has seen major projects that sidelined Indigenous voices or put short-term gains ahead of long-term well-being. This partnership is designed to be different: co-led by community members, grounded in human rights and guided by the principle of One Health—the idea that the health of people, the land and the water are inseparable.

“We recognize Indigenous people have their rights to development,” Wang says. “To Indigenous people, health is not just the lack of disease, not being sick, but it’s the well-being of people. And that well-being of people includes the well-being of the land, of the water.”

In his view, that’s what makes this moment so significant. Climate change is rewriting the map of the North, forcing hard choices. But it’s also creating a chance to reimagine nation building in a way that centres Indigenous and northern communities from the very beginning.

Ottawa and the Prairies back Churchill

Prime Minister Mark Carney has placed the Port of Churchill at the centre of his government’s new nation-building agenda. In August 2025, he announced that Ottawa will invest in modernizing the port. The project was singled out as one of the top candidates for fast-track approval under Bill C-5, Canada’s new infrastructure law. The move positions Churchill not only as a hub for Prairie exports like grain and minerals but also as part of Canada’s strategy to strengthen supply chains and assert its role as an Arctic nation.

Momentum is also building provincially. At the Council of the Federation’s summer meeting in July 2025, Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe signed an agreement with Arctic Gateway Group to expand rail and port infrastructure, lengthen the shipping season and unlock new trade opportunities for Prairie producers.

Where most people see problems, Bisons see solutions. Explore and meet UM researchers—like Feiyue Wang —who are changing lives in Manitoba and beyond.

Feiyue (Fei) Wang is a professor at the University of Manitoba and a Tier-1 Canada Research Chair in Arctic Environmental Chemistry. Wang directs the Churchill Marine Observatory and studies sea ice, northern contaminants and oil spill response in Arctic waters. Widely regarded as one of Canada’s foremost experts on Arctic environmental chemistry, he also leads major national and international research partnerships. Check out his discussion with UM President Michael Benarroch on the What’s the Big Idea podcast.

Security and defence in a changing Arctic

Nation building needs research — not just infrastructuree