Heather Gill-Frerking has spent much of her life in the company of the dead. The University of Manitoba anthropology grad is a world-renowned expert in a rare field. She uses high-tech medical imagery to analyze mummies and uncover anatomical secrets.

The face of the bog body known as Grauballe Man discovered in 1982 in Denmark // Photo by Sven Rosborn

Gill-Frerking [PhD/05] has studied many types of mummies, but she specializes in what are known as bog bodies, corpses that were naturally petrified by the unique chemistry of the northern European marshes in which they were interred. Bog bodies date back hundreds, or in some cases, thousands of years, and yet their skin and faces often appear disconcertingly lifelike.

Although some might find the prospect of studying desiccated cadavers macabre, Gill-Frerking has no such compunctions. She refers to her subjects as “my beautiful bog bodies,” and unlike many of her colleagues, does not regard mummies merely as research objects. “I believe mummies are still people, not that they were people. I treat them as patients. Using my skills, I bring their stories to life. I create a picture of who they were and how they lived.”

Gill-Frerking’s scholarly passion may be unusual, but then so is her employment background. Born in Manitoba but raised mostly in Frankford, a small town north of Trenton, Ont., she originally earned a bachelor of education because she planned on a career as a primary school teacher. She did teach for a while at an international school in Denmark, but has also held jobs working for a bookmaker, teaching convicts at a prison, and serving as a forensic technician for the police department in Belleville, Ont. In the meantime she also managed to get a master’s degree in archaeology from the University of York, and a PhD in biological anthropology from UM.

“

I believe mummies are still people, not that they were people. I treat them as patients.

”

Her interest in mummies was sparked when she viewed a photo of a bog body known as Tollund Man while taking a summer course in anthropology at Trent University. Unearthed in Denmark in 1950, the Tollund Man has been called the “perfect corpse,” chiefly because of the exquisite condition of his face and head. “I asked my instructor how that type of preservation was created. He said that no one really knows. I’m the sort of person who always has to find out the answer to those sorts of questions, so I started researching bog bodies to find out how the processes worked and immediately became fascinated.”

The Tollund Man lived 2,300 years ago and was so well-preserved in the peat and the cold it was initially mistaken as a modern-day murder victim. The mummified corpse is believed to be that of a man who died by hanging // hand photo by PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo; full body photo by Ian Dagnall / Alamy Stock Photo; close-up of head photo by Mummipedia Wiki / Fandom

In fact, Gill-Frerking became so enthralled that while pursuing her archaeology degree in England she conducted her own tests with stillborn piglets, submerging them in peat bogs for months at a time to determine how the brackish stew preserved their bodies. The study was not without its setbacks. “One decomposing piglet exploded in my face,” she recalls. “You don’t want a PhD in that, believe me.” But the unorthodox experiment drew attention, including an article in The New York Times, in which Gill-Frerking pointed out that her research had potential value for helping police to better predict the time of death in murder cases. It also led to the Canadian being hired to work with a museum in Germany.

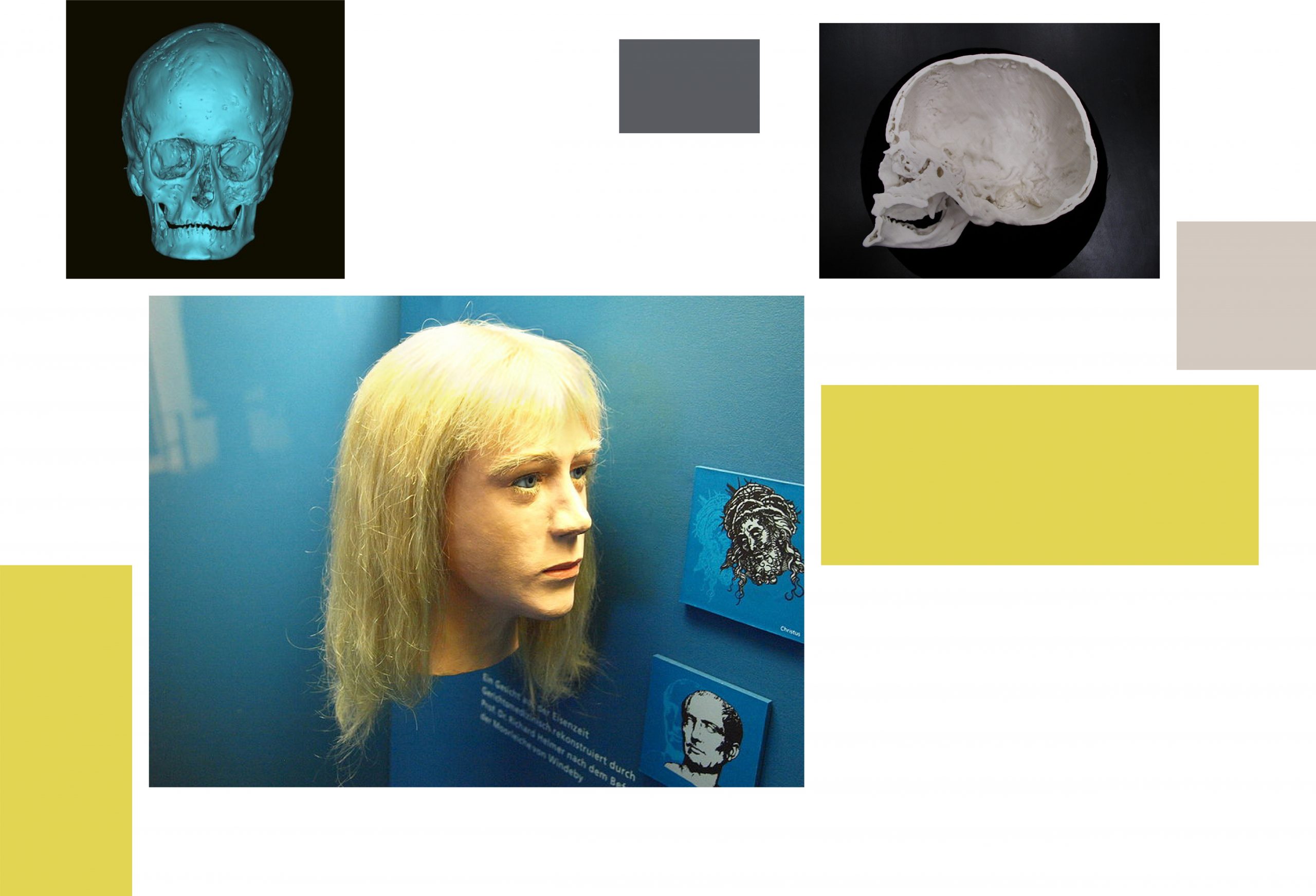

Before long she was making a name with her expertise in performing virtual autopsies using medical imaging tools. One of those cases made headlines when she examined a famous German bog mummy known as the Windeby Girl, whom scholars theorized was a teenage female adulteress who had her head shaved, and then was killed and thrown into a bog. A middle-aged man’s strangled corpse located only a few feet away was believed to be her lover. Gill-Frerking upended that dramatic scenario, establishing that the mummy was actually a young man, who most probably lost his hair to careless trowel work during the excavation, and who had actually perished from illness. Radiocarbon dating revealed the strangled man’s body to be 300 years older.

These 3-D renderings and reconstruction show The Windeby Child, who died in the first century AD. Heather Gill-Frerking revealed that the bog body unearthed in Germany in 1952 was that of a boy who died of natural causes // all photos supplied

Science has had a dramatic impact on the study of mummies. Until the late 1970s, these ancient bodies were still being unwrapped and sliced open to be analyzed, but the advent of CT scanners has changed all that. After a mummy is scanned, the data can be used to study the body in both 2-D and 3-D without having to damage it any way. The technology allows Gill-Frerking to deduce such things as age at death and an individual’s sex (“It’s not as easy as you may think”), find any artifacts hidden in bandages, or identify illness or trauma. Analysis of hair, fingernails, and stomach content can coax out other secrets. From this information she can often piece together life stories of the deceased, including their occupations. “It provides us with a window into cultures, heritage and the way people lived thousands of years ago,” she says.

“

It provides us with a window into cultures, heritage and the way people lived thousands of years ago.

”

Analyzing bog mummies with these tools is far more challenging than it is with embalmed Egyptian mummies or corpses that have been preserved by arid climates, because the peat dissolves the calcium in the bones, causing them to collapse and making it difficult to distinguish them from soft tissue like skin and tendon. The complexity of the science may be part of the reason why there are few experts in the field. In fact, Gill-Frerking is the only North American to ever do hands-on investigations of European bog bodies.

“Using the CT scanning, we can also create virtual and physical 3-D models of bones and artifacts,” notes Gill-Frerking. “We can create the virtual model on the computer screen and then send the file to a special 3-D printer to make an exact replica of the bone or object out of plaster or resin.” Some of these 3-D models were used at international exhibits that Gill-Frerking has been involved with, such as “Mummies of the World,” which toured North America in 2014 and featured mummies and artifacts from Egypt, South America, Europe, Asia and Africa.

Tollund Man is reanimated digitally via forensic reconstruction based on the skull. The reconstruction is made by Philippe Froesh from VISUALFORENSIC // Video courtesy of Museum Silkeborg via Vimeo

However, these days Gill-Frerking has shifted away from mummy consulting work. Instead, she is finishing up a degree in cultural and heritage law at the Vermont Law School. She has become disillusioned by the recent rise in black market trading of mummies and other antiquities and believes that the laws protecting artifacts are much too weak. “There is more law protecting a vase or a stone tool than human remains. I find that distressing.” Increasingly, she feels, ethical questions about the display of human remains will become a prominent public issue.

“

There is more law protecting a vase or a stone tool than human remains. I find that distressing.

”

Yet even as her academic focus moves from mummies to law, Gill-Frerking remains intrigued by bog bodies and the ongoing debate about how and why these poor souls came to end up immersed in peat. A number of the dead show signs of terrible trauma, including torture and mutilation. Were they ritual sacrifices or victims of crime? The question remains unresolved.

Gill-Frerking is more definite about her own final resting spot. She says she would like to be buried in a peat bog with her medical records so that scientists in the future could excavate her corpse and study her. “I’m very serious about it. There is a bog just north of Schleswig, Germany, where I’d love to be buried. Alternatively, Tregaron Bog in Wales would be a great spot to be interred. I buried some of my experimental piglets at Tregaron and it’s a beautiful place.”