Two decades ago, three people consecutively visited Diana Thorneycroft’s studio to look at her black-and-white photographs.

On the first day, an out-of-town curator who used to practice “S&M” shot Thorneycroft [BFA(Hons)/79] an appreciative you’re-like-me look.

Next, a Wiccan came and surmised Thorneycroft performed witchcraft too.

Lastly, a survivor of sexual abuse visited, and assumed Thorneycroft carried similar pain.

“Within a week I learned that people bring their own histories to art,” the Winnipeg-based artist says. “When I taught at the School of Art, a lot of my students wanted to control the reading of their work, and I told them to give that up.

At most you can control 50 per cent of the interpretation. The viewer’s history is what finishes a work of art.”

Don’t be afraid to talk about it, artists insist. No matter what you see, you get to own that interpretation.

“You shouldn’t be afraid to say what you think,” says painter Carole Freeman [BFA/76, BFA(Hons)/77].

There is no right and wrong reading; and even the artist’s explanation mutates.

“The artist can’t really give you the definitive meaning of the artwork. Talking and making things are two different things,” says painter Michael Dumontier [BFA(Hons)/96] to his collaborator Neil Farber [BFA(Hons)/97], who agrees.

“It’s not annoying to talk about my art,” Farber says, “but I’ll give you different answers every time.”

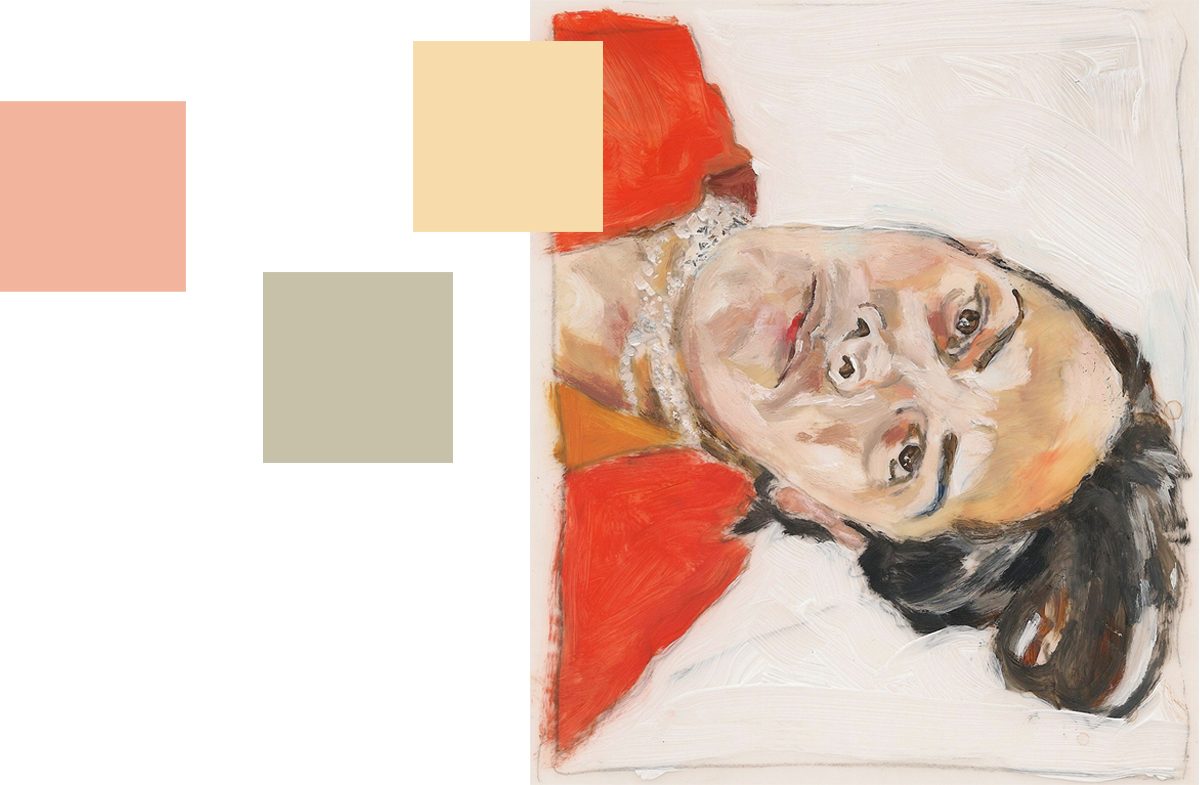

ARTIST: CAROLE FREEMAN

On the eve of launching a solo exhibit in Toronto, Freeman told The Globe and Mail she was a “re-emerging artist.” Navigating financial issues of single motherhood, she had put her painting career on pause for a predictable teaching paycheque. Many years later, a gallery offered her an exhibition, and in a flurry of four months she painted 200 portraits for Friend Me: Portraits of Facebook.

The Globe admired how she married art’s oldest genre with history’s most overstuffed portrait gallery. Today, her evocative portraits and narrative paintings of cultural, social, political and personal significance are exhibited around the world. Her portraits, New York Magazine says, “are beautiful meditations in paint.”

People’s faces infiltrated her childhood. Her grandfather and uncle shot portrait photography, as did her father’s best friend. The landscape of the human face intrigued her since she was young, but photography’s gravity never pulled on her; painting did. “The differences between a photographed and a painted portrait are, for me, time and surface.

A photograph is a moment or instant in time, though of course, capturing that instant is an art. A painting is produced over time so the act of creating, as opposed to capturing, is inherent in the painting….” But why paint? “I like the physicality of painting and the smells. I like confronting a blank surface and making something from nothing.”

DUCHESS AND DUKE OF WINTERPEG

Freeman moved away in her 20s and this painting was part of Something About Winnipeg, a solo exhibition in 2016 in her home city.

“I wanted to deal with the whole aspect of being born, and growing up, in Winnipeg and what that means…. This painting displays my love of art history, particularly the Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca and his painting Duke and Duchess of Urbino [a celebrated 14th-century portrait]. I made up two fictitious figures and added my teenage experience making and wearing nose warmers in cold Winnipeg winters.”

My first reaction was to laugh at the Duke and the thing on his nose. But I could relate‚ once I saw the title‚ having grown up in Winnipeg. There’s almost a sexual innuendo to the things on their faces…. It really placed me in late fall‚ when it’s already freezing but snow is not covering the ground yet. But you can feel it. The shading in the sky is perfect. And she really captures the landscape and people of the Prairies—the man looks pretty much identical to my grandfather. -Curtis Nowosad

That gizmo on the guy’s nose is too long‚ so it starts to suggest other things‚ anatomically‚ and it also suggests Pinocchio‚ which is interesting‚ but I don’t know if it’s supposed to. -Judy Anderson

This reminds me [of the cold‚ but] it makes me feel warmth: the clothing‚ the colours‚ the background. –Chris Schmidt

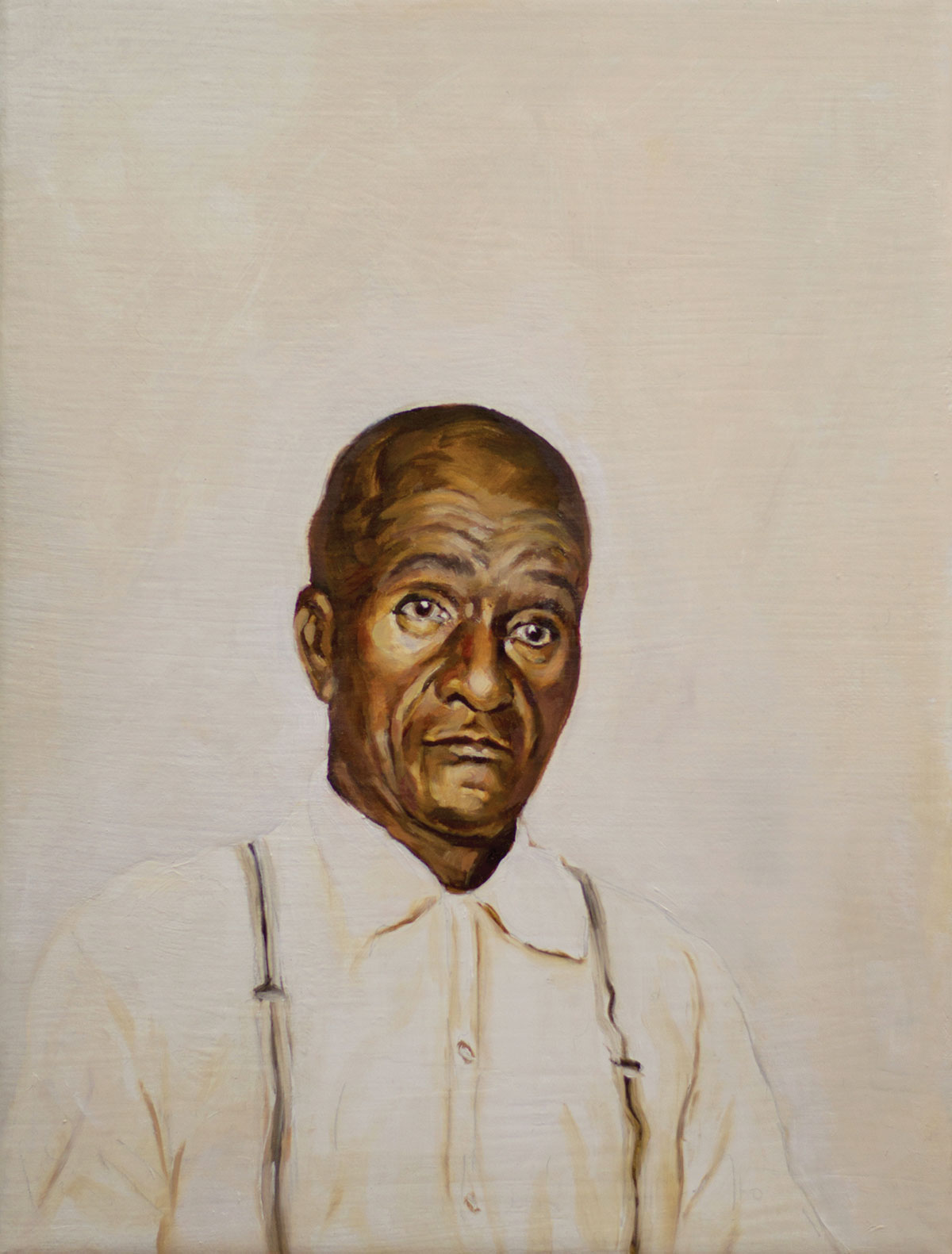

MOSE WRIGHT 1890-1973

This is one of 24 portraits unveiled at Unsung, Freeman’s debut solo exhibit in New York in 2018, which showcased little-known Americans who represent a range of still-unresolved political and social issues. Painted with oil on linen, like a Renaissance portrait, it’s heavily varnished to give the colours a pure sheen. “I wanted each one to be a little jewel,” she says.

In 1955, Mose Wright ignored death threats and testified in a Mississippi courtroom at the trial of two men accused of abducting, torturing and murdering his 14-year-old great-nephew, Emmet Till, who was falsely rumoured to have whistled at a white woman.

“I chose Mose as a subject because his story is still so relevant today. I’m horrified by everything that is going on in the States and everything in the world. I wanted to portray his vulnerability and his strength. I wanted to tell his story. ”

She painted this image from a black-and-white photograph she found of Wright sitting in his house. She was drawn to “this look [in his eyes], showing the horror and the heartbreak and the sadness.”

I initially thought he had a combination of fear and intensity in his facial expression. On the second look‚ I actually have a completely opposite view. I see forgiveness in his eyes. I see someone who is compassionate and understanding. These are not the easiest qualities for humans to portray‚ and I personally work very hard to better myself in this area. -Chris Schmidt

I have seen this photo before…. Just looking into his eyes and seeing the amount of bravery it would take to identify his nephew Emmet Till’s murderers in the face of such extreme racism‚ it gives me chills. The confidence it would take to stand up in a situation like that‚ knowing that he would need to leave his home in Mississippi forever (which he did)‚ is really astounding. I really think she captured it well. She close-cropped it a bit and really captured his facial expression instead of focusing on the other aspects of the photo. She’s really focusing on the man and what he’s gone through and the way he carries that all in his face. -Curtis Nowosad

He’s got nice eyes‚ and he needs a hug. It’s a very interesting composition. His head is very central; it’s not a portrait in the same proportion that a portrait would be in. It makes him look like a smaller presence‚ in a way. -Judy Anderson

ARTIST: DIANA THORNEYCROFT

When the Manitoba Arts Council gave her its Award of Distinction in 2016, they praised her ability to make art that “hovers on the edge of public acceptance.” Indeed, nearly 20 years earlier she received death threats for her exhibit Monstrance, which used rabbit corpses. “I have never made work with risk-taking in mind. It just happens that the things I am interested in are viewed by some people as controversial,” she once told the National Gallery of Canada. Her work has been exhibited across North America, Europe and Asia, winning many awards, most recently the 2019 LensCulture Award for visual storytelling.

Toys stuff her Winnipeg studio. Individual shelves are dedicated to particular items—guns, bears, moose, howling wolves. Animals appear in much of her work, acting as innocent witnesses to horrific events, or helping convey dark humour. Thorneycroft likes the collision the grotesque affords: “At first you are attracted to it, and then you get this pow! There’s the oscillation between the beauty of the piece and this black humour.”

She arranges her tableaus, darkens her studio, holds open her camera’s shutter, and then illuminates the set with a flashlight to create drama. “I don’t see myself as a traditional photographer who takes photographs. I am a visual artist who makes photographs.”

GROUP OF SEVEN AWKWARD MOMENTS (MAPLES AND BIRCHES AND WINNIE THE POOH)

This piece plays on the iconic landscape paintings from 1920-33 by the men who make up the Group of Seven, paired with Winnie the Pooh and the black bear the cartoon is based on—Winnie the Bear (named after Winnipeg).

“I was looking for Canadian stories that relate to our culture and had an element of humour,” says Thorneycroft. “The whole history of Disney owning Winnie the Pooh and the original story of Winnie the Bear always bugged my ass—that we can’t talk about Winnie the Pooh without being sued by Disney. It just seems like, C’mon, it’s our bear. So this is when I thought that Winnie the Pooh had to be killed—had to be put down—and Winnie the Bear was the one to do it.

“The painting in the background is by A.Y. Jackson. When I first began this series, my original intent was to subvert the Group of Seven. Here are these revered dead white guys, and I was going to take their iconic landscapes and subvert them but also embrace them and bring them back to contemporary conversation. What I didn’t expect is that I actually fell in love with much of their work. If I could infuse humour into it, all the better. We don’t use a lot of humour in contemporary art, and it was my goal to encourage as much laughter as possible. Because awkward moments can be funny.”

Is Pooh stealing their honey? I don’t know. I love how casually the other bears are sitting around. -Curtis Nowosad

This reminds me what life is like as a CEO. Sort-of the idea that you’re in the spotlight—you’re Pooh—and if anything bad happens‚ it all points back to you‚ whether it’s a finger or a gun. He has a smile. He looks rather content and happy‚ and I think that’s similar to myself. I am always happy and energetic‚ despite what comes with my position. -Chris Schmidt

It’s almost like‚ life is no picnic. The “Teddy Bear’s Picnic” song rings in my head: If you go into the woods today‚ you’re in for a big surprise. The shininess of the bear with the gun is somehow ominous against the poor little fluffy Pooh figurine. He’s a stranger to them‚ for sure. A bear isn’t a bear. You could get into all kinds of xenophobia things; I don’t know if that’s part of the thought. -Judy Anderson

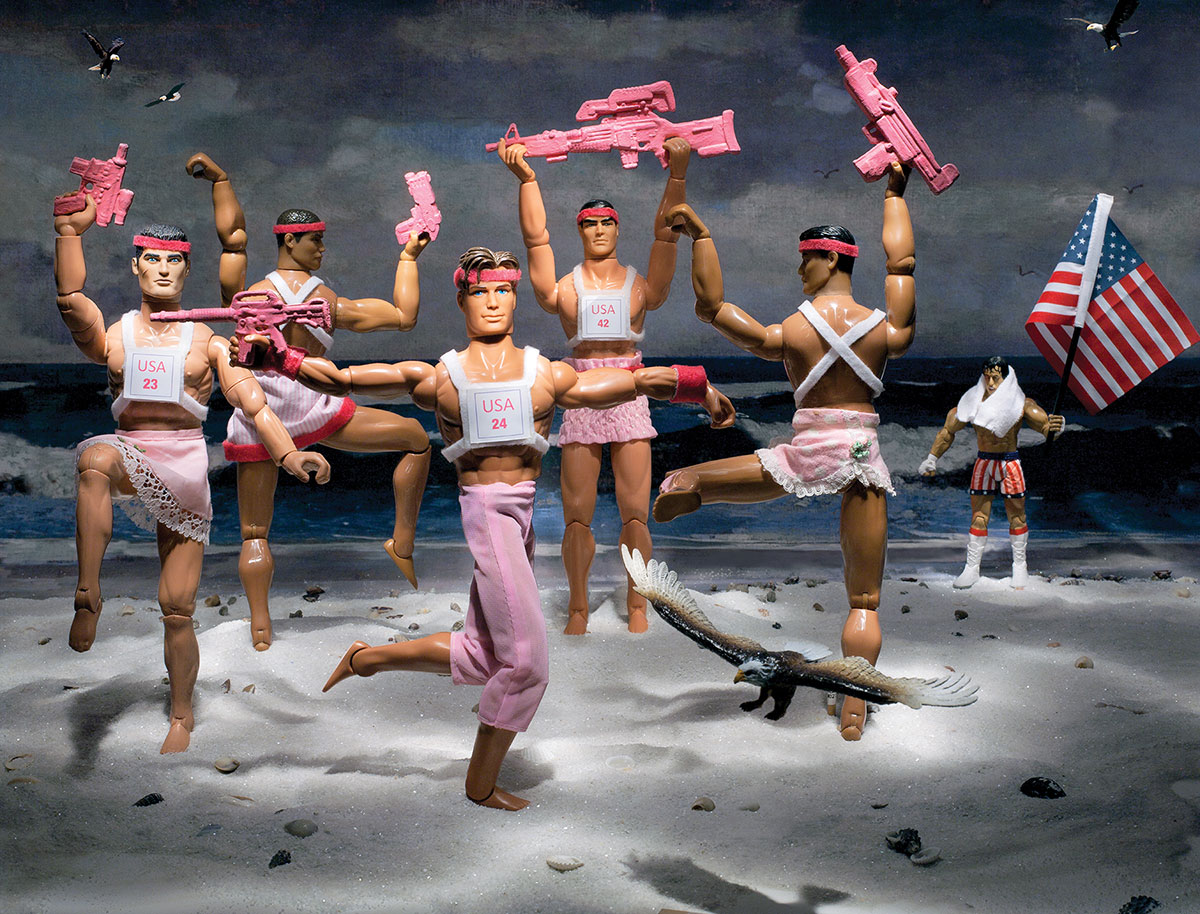

NRA SPONSORED RHYTHMIC GYMNASTICS COMPETITION (TEAM USA PERFORMS WHILE CANADA AND FRANCE LOOK ON)

“I hate the NRA. It’s such an evil organization,” she sighs. The central piece in a three-part series, this work pokes fun at the National Rifle Association. “I have a lot of G.I. Joes in my collection and I noticed that their hands are made to hold guns, but with a simple twist, their hands become quite effeminate. And I speculated that there are probably not a lot of effeminate men in the NRA. Although there is a gay gun-rights group called Pink Pistols. I’m not poking fun at them. I just wanted to show these macho dolls doing rhythmic gymnastics, which is exclusively for women in the Olympics. I had so much fun. I was laughing so hard when I was making this.”

I’m worried about the eagle flying so low. Eagles don’t usually fly so low unless they are scavenging something. It’s kind-of like it’s lost‚ or maybe it got shot out of the sky. -Judy Anderson

We always have an office party once or twice a year and this basically sums up the office party. Everything is chaos. I don’t even know what to think of this. I feel kind of mixed emotions. The size of the guns is concerning‚ but then there is this odd celebratory excitement and dancing…. It’s very symbolic of the U.S. and the praise of no gun laws. -Chris Schmidt

It is surreal as hell. I love that someone was able to dream it up. What’s interesting to me‚ as a musician‚ is that it puts me in a headspace. With music‚ I sometimes wonder‚ how did they do that? Sometimes the answer is very simple; sometimes it’s very complex. I love the absurdity of this one. -Curtis Nowosad

ARTISTS: MICHAEL DUMONTIER & NEIL FARBER

They sit across from each other at a table burdened with paint, tape and markers. Music always plays in the background; lately it’s been folk. They tried making music together after they met through a mutual friend in class at UM in 1995, but that venture flopped. The art thrived though, beginning with a collage Dumontier made out of Farber’s drawings of soldiers.

They have successful solo careers, but they also meet every Wednesday at 9 p.m. at Farber’s River Heights home, staying together until 1 or 2 in the morning to create works that sell in galleries in Montreal and California (their European galleries closed after the 2008 financial crisis), and earned them a 2014 Sobey Award nomination. Canadian Art magazine calls them “two of the funniest, smartest guys in Winnipeg.”

They take turns starting and finishing each other’s sentences, and together they explain they are into flowers now. Farber spends most days strolling through Assiniboine Park, writing dozens of aphorisms and quips. He brings the words to Dumontier, who paints something to accompany them. “These aren’t like anything we would have done 20 years ago,” Farber says, “but it’s the same area we’ve always liked: sad stuff, and funny.”

IF WE DON’T ALL FIND LOVE‚ WE ALL LOSE

Farber: “Who is the ‘we’?”

UM Today: “I was thinking it is all of humanity.”

Farber: “Yeah, society, I guess. You should build a society that works.”

UM Today: “It was originally uplifting, but then I got depressed.”

Dumontier: “Yeah, that’s the general flavour.”

Farber: “There’s no way this works out other than we all lose…. I think we’re moving away from our dark humour. We’ve gone pretty dark—”

Dumontier: “It’s pretty melancholy most of the time.”

Farber: “I think it’s lighter—”

Dumontier: “More sentimental…. These sort-of have this vintage greeting card [feel]….

Farber: “We wanted the ‘we’ to be part of a group.”

Dumontier: “You could imagine, is it [the flowers’] relationship, or just a community idea? I don’t like thinking of it in terms of the flowers falling in love with each other, and there’s an odd number, so that wouldn’t be ideal anyway. I prefer to think of it in general.”

For me the word “love” in this means happiness. And for everyone‚ happiness comes in a different form. And what is embodied well for me is—whether it’s business or personal—if not everyone is happy‚ we all lose. There’s this communal sense of teamwork and helping each other. -Chris Schmidt

I didn’t interpret love as finding a romantic partner. I went to the global message. We all need to find love in all of its capacities. But if you grow up without love‚ you’re going to create a lot of problems for a lot of people‚ especially yourself. -Curtis Nowosad

The flowers are telling me the artists feel that maybe there are many kinds of love and you can have a wonderful life enjoying what you love‚ even if it isn’t an individual. Maybe it’s about finding people to love us‚ and maybe the flowers are symbolic: that everyone will give a different token of that. -Judy Anderson

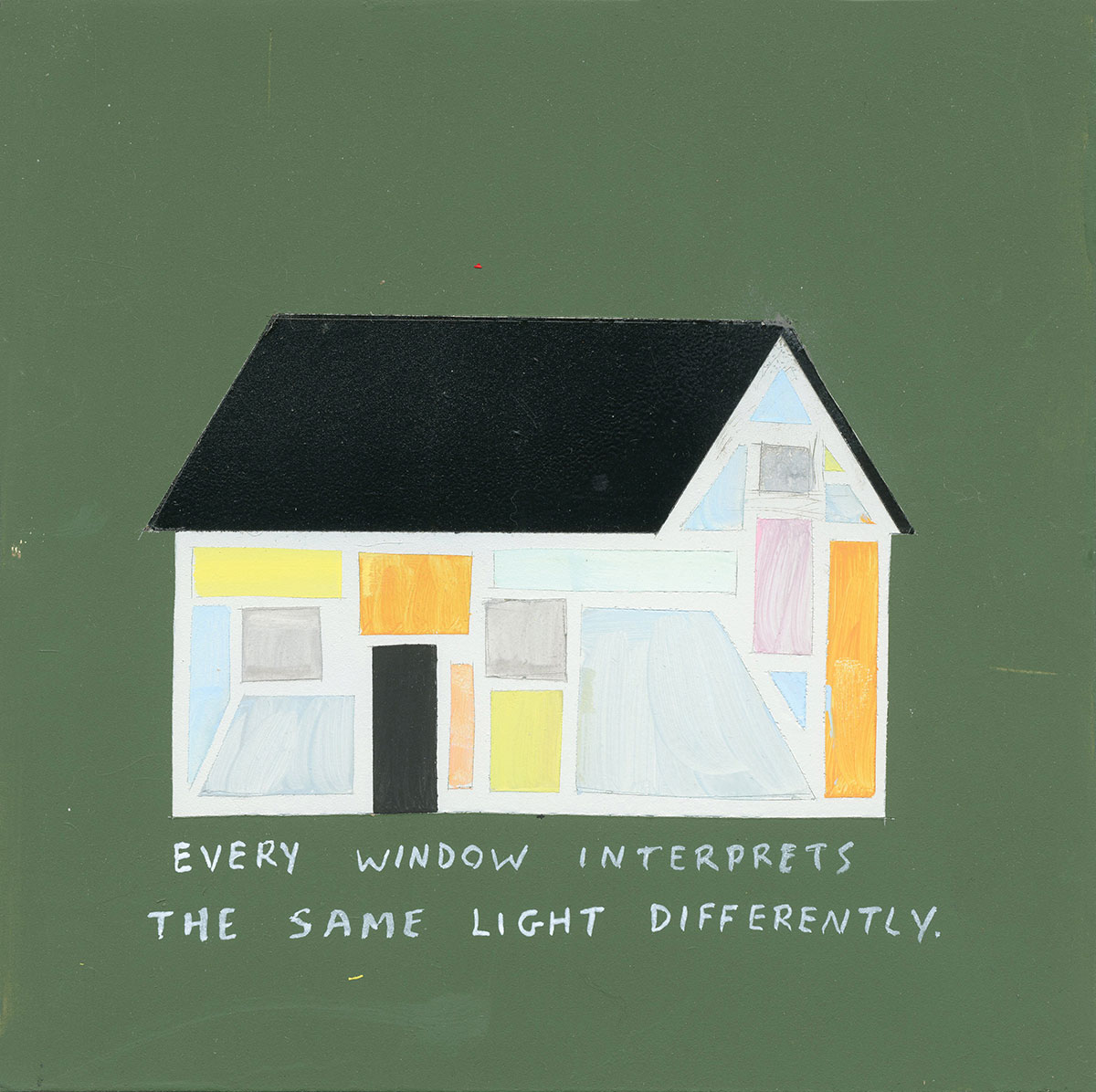

EVERY WINDOW INTERPRETS THE SAME LIGHT DIFFERENTLY

Farber: “We’re pretty much telling you what to think with the words.”

Dumontier: “Yeah, it’s pretty literal. Well, not literal—”

Farber: “Some of them are a bit confusing—but we want you to get it one way. We’re not giving you an option.”

Dumontier: “I mean, it’s a metaphor. Of course the words can be interpreted in different ways. Sometimes people take them differently than I’d expect.”

Farber: “I think we came up with this idea together and reworked it a bunch because this is one that had to be worded right.”

Dumontier: “We’re pretty in sync. There might be stuff one of us likes more than the other but—”

Farber: “It doesn’t matter. We make hundreds of paintings a year.”

This is funky. Every window does show you what’s outside differently‚ and if you’re outside‚ it definitely shows you different parts of what is inside. Some want to lead you in by their perspective‚ and some are opaque and make you think they are possibly a door rather than a window—they restrict you from seeing something different. -Judy Anderson

This painting essentially—perfectly—summarizes employees. Every employee is different. Everyone has different wants and needs. And everyone interprets what I say differently. It comes to this idea that communication is so‚ so important‚ not just in business‚ but in life. -Chris Schmidt

The windows are important. And the saying really speaks to me. We’re all filtering everything through our own personal experiences. We’re all perceiving things based on our past experiences. -Curtis Nowosad