A small, corroded screw has scientist Debbie Armstrong’s full attention. On this Wednesday morning, she and colleague Jeff Gao are hunkered over a device on the roof of their research trailer at the University of Manitoba’s Churchill Marine Observatory (CMO).

The disintegrating screw within this air monitoring box is stripped and she and Gao—collaborators at this first-of-its-kind-facility for Manitoba—are urgently troubleshooting a fix before their flight back to Winnipeg.

“We’ve used this in the Galapagos and Canary Islands and never had a problem,” says a hurried Armstrong.

But Manitoba’s subarctic is different. With its salt spray off Hudson Bay and -50 C throughout winter, the elements quickly take a toll.

Churchill, it seems, is a place where maintaining anything requires some special care.

”Debbie

and Jeff Gao [PhD/2023] on the roof of the CMO’s atmospheric trailer” src=”/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/um-today-open-water-armstrong-gao.jpg” alt=”Jeff Gao and Debbie Armstrong work to fix something on the top of their research trailer”]What’s lesser known about Churchill than its wild polar bears, pods of beluga whales and frequent aurora borealis is that it’s home to Canada’s furthest north and only deepwater seaport reachable by train. The town sees itself as an untapped international shipping hub and, while not a new idea, it feels like there’s growing momentum as of late, says Feiyue Wang, a Canada Research Chair at UM and Project Lead of CMO.

This environmental chemist, who studies contaminants like mercury and oil in Arctic sea ice and waters, insists people are starting to think of Manitoba as something beyond a prairie province. For years Wang has called Manitoba “a maritime province,” raising eyebrows at conferences on the east coast, the west coast and everywhere in between.

“But now it’s become somewhat of a catchy phrase,” he says proudly. “It’s even being used by the Premier [Wab Kinew].”

The Port of Churchill

Increasingly longer stretches of open water in Hudson Bay due to climate change means new access to shipping routes to Asia, Europe, Africa and the Americas, connecting Manitoba to the global supply chain like never before. There’s ongoing talk of investing in infrastructure, of transforming the existing century-old port and the outdated rail system that leads here.

Progress via partnerships

Michael Spence, who’s been Mayor of Churchill for nearly three decades, says a reimagined port is key to their future; tourism isn’t enough. The potential economic boon and improved food security this could bring to Churchill and nearby communities, including Nunavut, are undeniable. (Right now, a four-litre jug of milk in Churchill’s grocery store costs nearly $11.)

One of only about 10 residential streets that make up the town of Churchill

Hudson Bay is already ice free for six months of the year. Scientists predict it will be essentially ice free year-round by 2100. The shift would provide Canada with a third seaway. So how does one properly prepare for this opportunity? That is, with consideration of the health of the land, the water, the people and the animals in such a remote and fragile ecosystem?

“It’s all about finding where you need to go. How do we find a balance…so we’re not disrupting what we have?” says Spence. “We’re very fortunate we have research and science as a partner.”

”Brendan

, whose UM graduate student research looked at beluga whale behavioural patterns in response to boats and environmental conditions” src=”/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/um-today-open-water-mcewan-spence-ausen.jpg” alt=”Brendan McEwan, Mayor Mike Spance and Emma Ausen ride in a boat”]For decades, UM scientists have acted as global forecasters of the pace of climate change’s impact in the North. They’ve monitored fluctuations to the populations and behaviours of polar bears and beluga whales, to the ice, to the water, to the air—providing a well-established baseline to identify when something’s amiss. The latest addition of the $45-million CMO bolsters this monitoring network. Researchers want to offer the community not only data but tools to help navigate new considerations.

A polar bear strolls along coastal rocks in late August. Come fall, the bear population on the tundra rivals that of Churchill residents (about 900) as the planet’s largest land carnivores await freeze-up to go on the sea ice to hunt seals

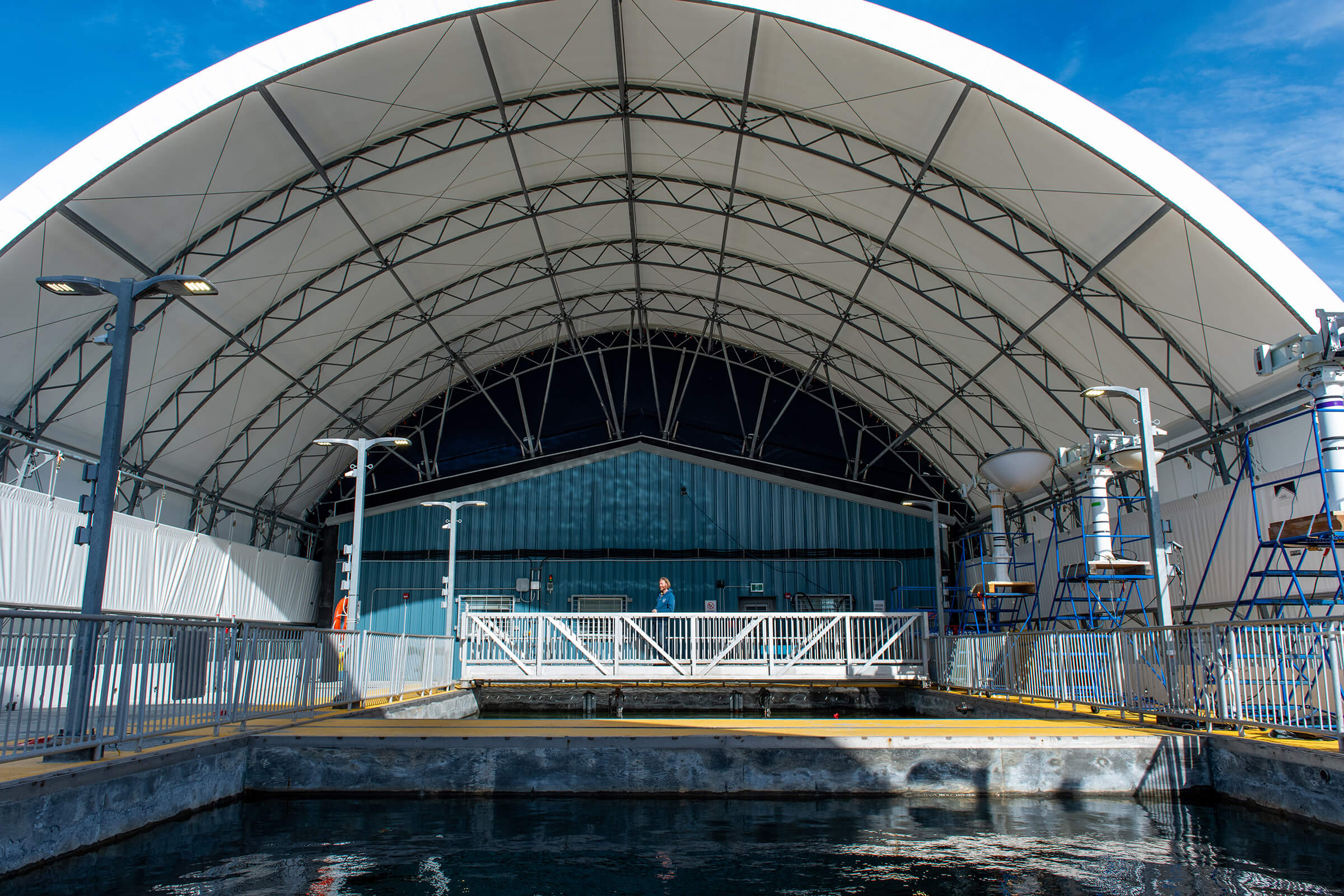

Charting new waters with specialized facility

Increased ship traffic comes with new risks, including the potential for oil spills. UM scientists are developing custom aerospace technology that could be adopted by locals, including radar-equipped drones to quickly flag leaking contaminants.

At the CMO’s official opening in August, visitors toured the facility’s two pools that pull water in from the Churchill River estuary and create a miniature Arctic Ocean. It’s where Eric Collins, researcher in UM’s Department of Environment and Geography, will safely mimic oil spills and investigate which oil-degrading microbes—what he calls “nature’s first-responders”—could potentially clean it up. While there’s more examples of oil disasters in non-Arctic conditions—like the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion off the coast of Luisiana—Collins wants to know how well microbes (such as the marine bacteria Alcanivorax) breakdown oil in sub-zero conditions.

“Microbes cleaned up far more oil during that spill in the Gulf of Mexico than human efforts did,” he notes.

The CMO’s Ocean-Sea Ice Mecocosm Facility, with its retractable roof open to blue skies

The facility’s design minimizes any progress-impeding pitfalls of doing research in extreme environments. The pools are covered by a retractable roof that faces up to 100 km/h winds, allowing for outdoor sea ice experiments but also shelter. Two labs with a cold room allows for on-site processing and analysis of samples. And the radar technology that scans the pools has a permanent monitoring space.

Solutions through satellite

A better understanding of how the radars at CMO detect and interpret water and sea ice properties can then be scaled up to give scientists a new window into how to decipher information already being collected by satellites around the world. Advances in this field of study could eventually substitute for fieldwork in remote locations but, so far, there’s still the risk of misinterpreting oddities.

Using sea ice in a pool on the university’s Fort Garry campus, 1,000 km south of Churchill, Dustin Isleifson [BSc(EE)/2005, PhD/2011] says their radar detected oil 18 hours before it revealed itself on the ice surface. An Associate Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Isleifson looks forward to testing this on location using sea water from Hudson Bay, with all its built-in biology. These experiments at CMO begin in November.

On land and water

The waters of Hudson Bay, adjacent to the facility, are well travelled by the CMO team. Their mid-sized 20-foot vessel, the William Kennedy, allows researchers to explore the little-known areas of Hudson Bay closer to shore, where the much larger Amundsen icebreaker doesn’t typically access.

C.J. Mundy [PhD/2007], a co-lead at the observatory and the Chief Scientist on this repurposed crab fishing ship, studies ocean processes and algae. His work reveals how climate change affects key players in the marine ecosystem: Algae supports all species from its spot at the bottom of the food chain.

He investigates and monitors algal diversity and production by water sampling and via oceanographic moorings across Hudson Bay, some collecting data for up to a year, aided by sensors and a remote-operated robot that provides video of the ocean floor.

“As the sea ice is melting earlier, so does the spring ice algal bloom. This shortening of the growth season will have implications on the ecosystem as the ice algae are key to the food web, providing an early pulse of energy for certain critters in the water that are key to feeding bigger critters, like whales. So without that ice algae, we have a risk of losing that true Arctic food web that currently resides in Hudson Bay,” says Mundy.

Oceanographer C.J. Mundy prepares for water sampling on the Churchill River estuary. Aboard the much larger William Kennedy, he lowers in heavy-duty equipment for measurements at various depths across Hudson Bay

Life in the North

Simionie Sammurtok, Mayor of Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut, travels with Spence and Wang across the country to speak to the challenges and the possibilities in the North.

From his hamlet where locals hunt caribou, walrus and beluga, Sammurtok has for years witnessed the effects of climate change. His list of observations is long: less snow, stronger winds, temperatures rising to 30 C, the arrival of new species in the region (from beavers and ducks to sharks and killer whales), more polar bears coming inland, parasites in walrus meat, and the shrinking sea ice local hunters must contend with.

“We don’t get ice until December. It used to be October. It’s getting later and later. Before, it was five or six metres thick. Now it gets about three metres thick,” Sammurtok says. “This kind of research has to be done.”

Simionie Sammurtok, Mayor of Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut

Mitesh Patel [BSc(ME)/2020,MSc(ME)/2023], a mechanical engineering technologist at UM and CMO collaborator, met with Sammurtok and other communities in spring to figure out how he could build a custom satellite for what they need. They’re exploring airships to hover above hunters as they travel, with radar technology aboard that measures and livestreams sea-ice conditions underfoot and provides cell phone coverage in case of an emergency.

“The idea is we could put satellite-based connectivity equipment on the airship, so it does all the heavy lifting and it’s flying in high altitude. And then it pipes down that network to the people who are on the ice,” Patel explains.

Mitesh Patel works on a drone in the CMO’s garage area

Today the learning is reciprocal between the people of Chesterfield Inlet and UM as both work to better understand what’s happening and keep hunters safe. Sammurtok says he started sounding alarm bells about climate change to the government in the 1980s to no avail.

David Barber [BPE/82, MNRM/88], the founder of UM’s Centre for Earth Observation Science, worked tirelessly for decades to help shift the spotlight north before his untimely death in 2022—the CMO was also Barber’s vision.

Looking at the past to predict the future

At the inaugural Churchill Barber Symposium here this summer, UM’s Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, a palaeoclimatologist, shared how investigating the region’s rich glacial history will help forecast future climate shifts.

Danish scientist Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, a Canada Excellence Research Chair in Arctic Ice, Freshwater-Marine Coupling and Climate Change, in Churchill, Man.

She spends much of her time ten metres below the Greenland ice sheet sampling ancient ice to identify reoccurring warming patterns. Her look at past climate shifts around Hudson Bay reveals a lifting of the land—from a previous glacial melt thousands of years ago—which suggests, surprisingly, sea level will rise in this coastal town over the next century. Monitoring how much would benefit planning for port infrastructure, she says.

Dahl-Jensen will head even further north, to Axel Heiberg Island, in April to retrieve ice cores from the Mueller Ice Cap. The expedition will be Canada’s deepest ice coring to date.“It’s up to 700 metres deep and we hope to get a really long climate history there,” she says.

A tight-knit town

It’s science-related conversations like this that you might overhear at the local Tundra Pub. Tourists to this fly-in town—this week, from Knoxville, Tennessee, and L.A.’s North Hollywood neighbourhood—might also notice a cast of characters that repeat in different roles: The person working at the town’s health centre is also the one checking in luggage at the air strip. And no one drives by without a wave.

Wang feels a connection to this place and its people. This summer he wanted to be there to support the Indigenous and community-owned Arctic Gateway Group (AGG) when they hit a milestone. The company owns and operates the Port of Churchill, as well as the Hudson Bay Railway, and on Aug. 16 celebrated the first ever shipment of critical minerals out of Churchill to Europe.

An historic step

Upwards of 100 rail cars of zinc concentrate from Snow Lake, Man., arrived in town over two months and was kept at a recently built storage facility on site—another first in 20 years at the port.

Wang, like Spence, talks about finding balance.

“That was quite something to see this gigantic supply vessel,” says Wang. “We’re scientists. We’re not developers. We’re not policymakers. From what we see, from what we hear, development is inevitable…so how do we do this in a balanced way so it is economically viable but also culturally sensitive and environmentally sustainable? We want to make sure it’s developed appropriately.”

That’s what a new, major research initiative, known as REACH, is set to achieve. Led by Wang and co-led by Spence, Sammurtok and several other community members and researchers, REACH aims to assess benefits and impact, determine feasibility and develop risk-mitigation measures to support the development of a reimagined northern seaway via the Port of Churchill and Hudson Bay.

Beluga whales swim in the Churchill River estuary near Churchill's Port

Provincial and federal governments invested $60 million to improve the port and rail line in 2024. Spence, who is Chair of the AGG, says they’re building more than physical structures, calling it “a new era of economic development and international trade for northern Manitoba.” All these efforts support economic Reconciliation, he adds.

‘A new era’

Cyril Fredlund, a technician who looks after the year-round maintenance at the CMO, grew up in Whale Cove, Nunavut, before moving to Churchill some 40 years ago. He feels hopeful about the attention the town is receiving as of late. (The observatory’s opening made the front page of The Globe and Mail.) He says any resistance to increased shipping here, which the longtime resident believes is minimal, can be attributed to human nature. We can all be leery about change.

“We naturally like to have things the way it is. We’re comfortable with it, even if it has problems,” the 72-year-old says.

CMO staffer and longtime Churchill resident Cyril Fredlund on the facility’s grounds

Churchill’s seasonal celebrities will become scarcer as the bears’ sea ice habitat succumbs to global warming. UM polar climate scientist Julienne Stroeve predicts this will happen as early as the 2030s to 2060s.

Becoming known as something other than “The Polar Bear Capital of the World” would take some getting used to. On this sunny afternoon, there are no bears in sight and Fredlund didn’t have to fire his bear banger—a noisemaker he always has on hand in case their curiosity brings them too close to the facility.

With Fredlund the last to lock up the marine observatory at the end of the day, it feels apt to give this Churchillian the last word here, too.

“Churchill is a diamond in the rough that people have tried to bury and to see it actually being polished, as it were, is very good,” he says. “It’s an asset to Canada that has not been realized to its full potential. And it’s good to see.”

Watch CMO researchers in action in Churchill // video by Mark Neufeld

WRITER’S NOTE //

Growing up, family friends ran a hotel in Churchill and I remember how oddly fascinating it was to hear about locals carefully trick or treating among the polar bears. To an over-imaginative kid, it felt like another planet. Remote. Mysterious. A land of roaming beasts and smiling belugas. Our friends had two giant St Bernards—Higgey and Hershey—who became playful supporting actors in this narrative.

It took me four decades to get to Churchill to see for myself. “It’s magical” is what I keep telling people. Not just for the reasons above but for the way the people here connect and share knowledge. A local who’s spent a lifetime on the sea ice knows as much or more about climate change as a scientist who’s made it their career. Everyone has something to teach and together they’re learning how to shape the next chapter.

Want to continue the conversation? UM President Michael Benarroch sat down with Feiyue Wang to talk about Manitoba’s Arctic corridor on the What’s the Big Idea? podcast

This story won the Gold 2025 Prix d’Excellence Award for Best Feature Writing – English from the Canadian Council for the Advancement of Education.

Thank you for your article